Snowy scenes, treasured gifts and Christmas letters: the collections of Royal Museums Greenwich contain a wealth of festive items. With the holiday season in full swing, we highlight some of our favourites, from one of the earliest maps of the North Pole to a festive menu from a battlecruiser.

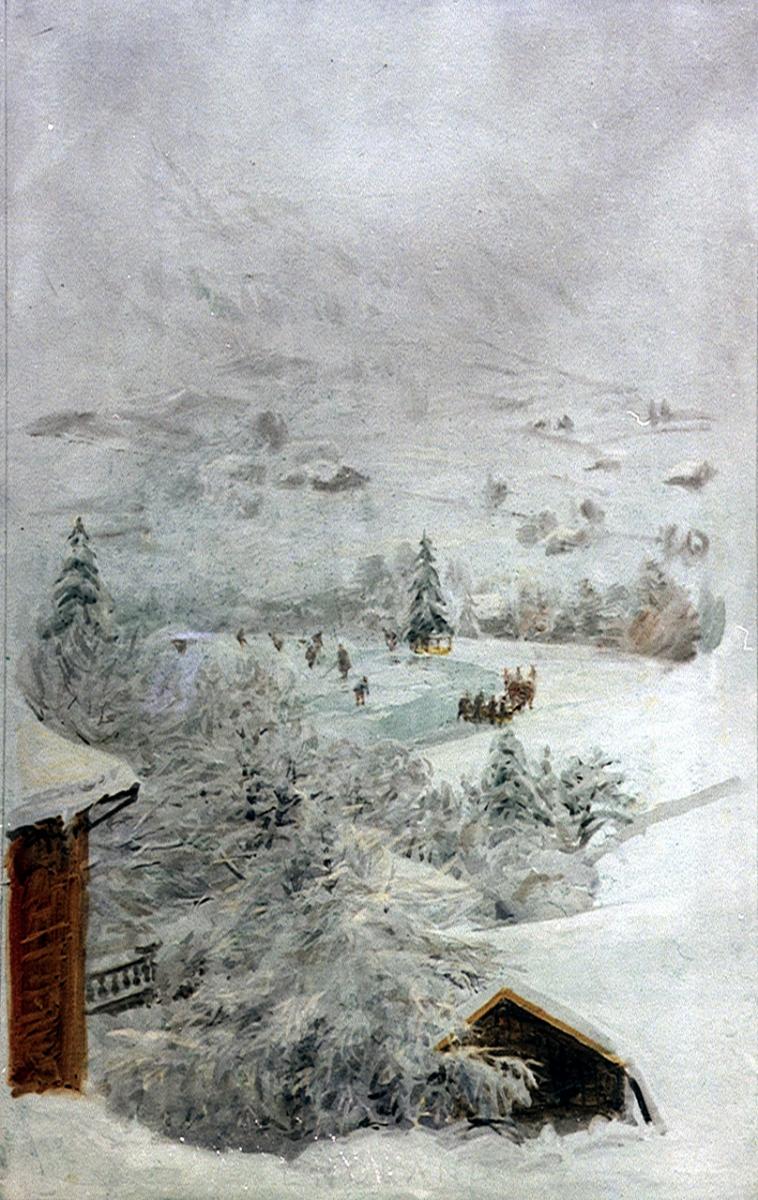

An alpine scene

One of the Victorian era’s most prolific painters, William Lionel Wyllie is best remembered for his marine artworks. He was also a seasoned traveller, and journeyed frequently to Europe, recording the places he visited in sketches and drawings.

This watercolour of a Switzerland snowscape showcases Wyllie’s fine attention to detail and technical ability. “Wyllie has used feathery brushstrokes to indicate the snow-laden branches of the trees surrounding the chalets in the foreground,” says Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art (Post-1800).

Wyllie’s wife, Marion Amy Carew, frequently accompanied him on his travels. Katherine explains that Switzerland was particularly nostalgic for the family. “It was a special place for the couple, having been the location of their wedding in 1879,” she says. “This watercolour is much later and was perhaps painted during a skiing holiday.”

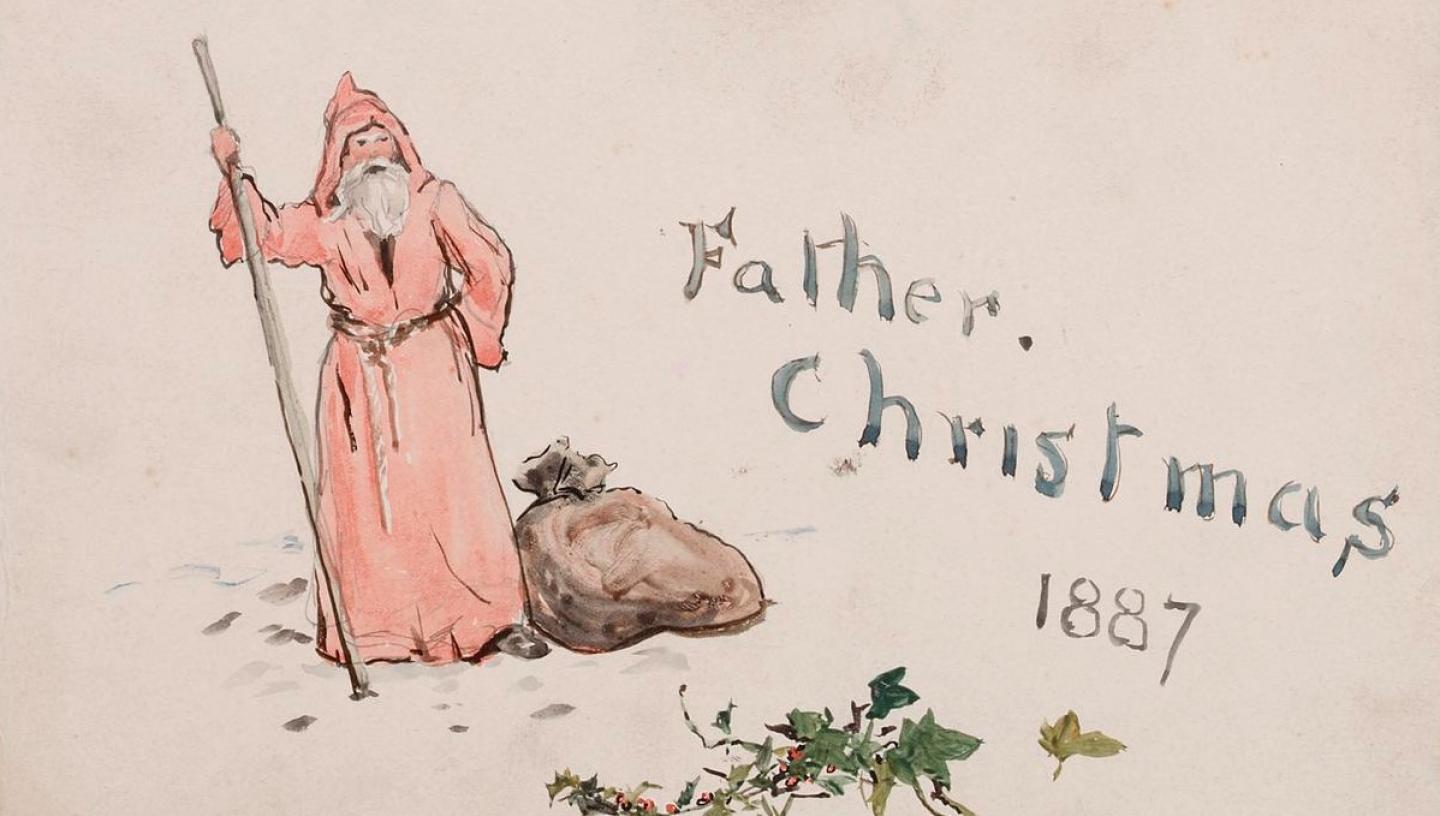

Christmas celebrations

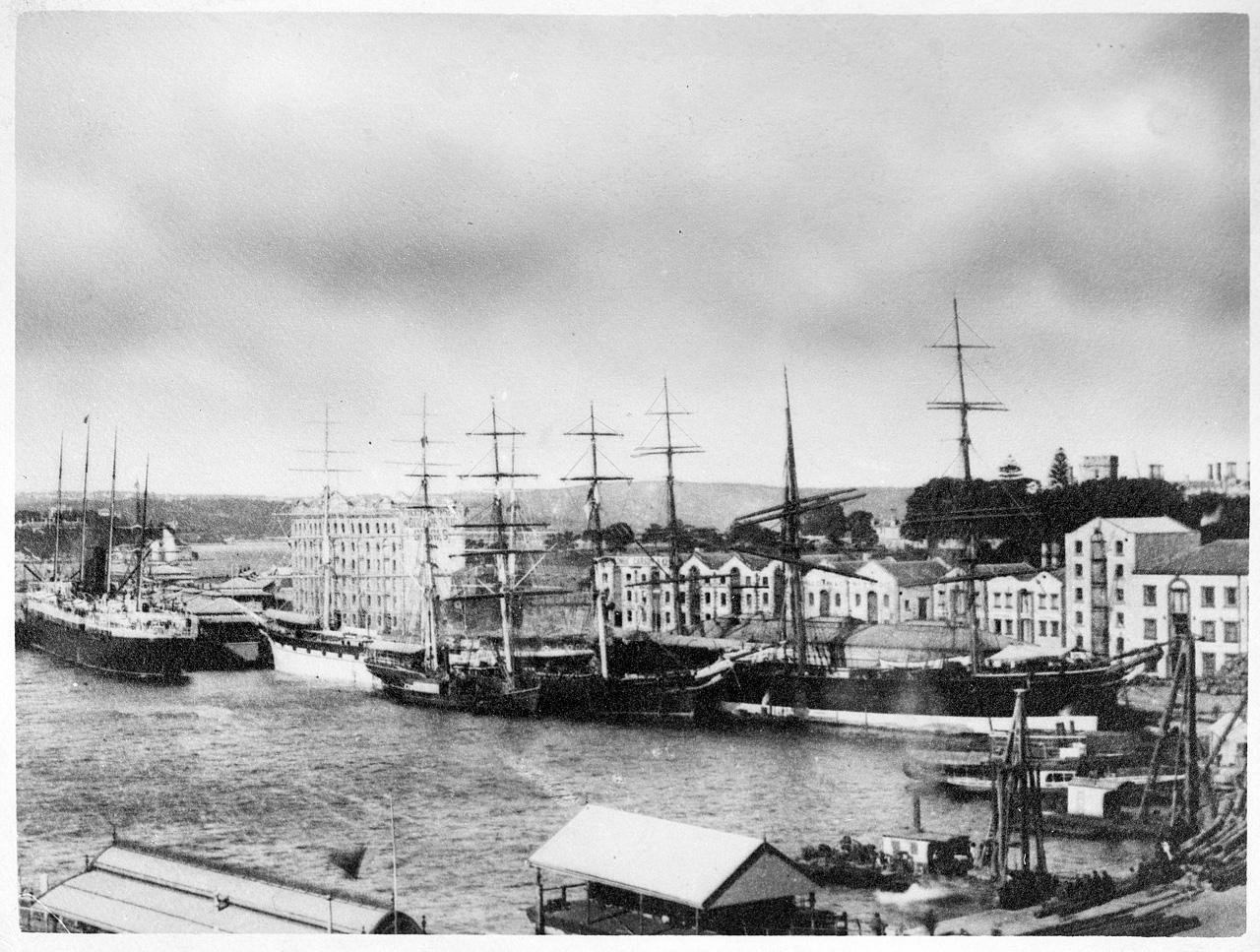

For the crew on board Cutty Sark, Christmas was very much a working day. The team would have worked to maintain and manoeuvre the ship. If in port, the crew would be supervising the stowing of cargo or preparing the ship for its next journey.

Built in 1869, Cutty Sark had a varied working life: between 1870-77, the ship was involved in the tea trade, transporting tea from China to England. A few decades later, from 1883-1895, the ship served the wool trade, carrying cargo from Australia. As a result, Christmas on board Cutty Sark was often spent in the southern hemisphere.

Letters from the crew give an insight into Christmas at sea. In a letter dating from 1880, apprentice Charles Sankey provides an account of the festivities the crew enjoyed in Singapore:

“Christmas came and went with its festivities. We decked the ship out in all the bunting we could find, and the harbour looked wonderfully gay, with every ship's flag flying. The people of Singapore take a personal interest in the sailors who come to their port, and entertained us in true Christmas spirit, for these sailors as a rule can never repay, and may never come to this port again.”

Other crew members missed their family Christmas traditions. In September 1894, faced with the prospect of spending Christmas on board, apprentice Clarence Ray writes to his mother asking if she could save “a piece of plum duff for me.”

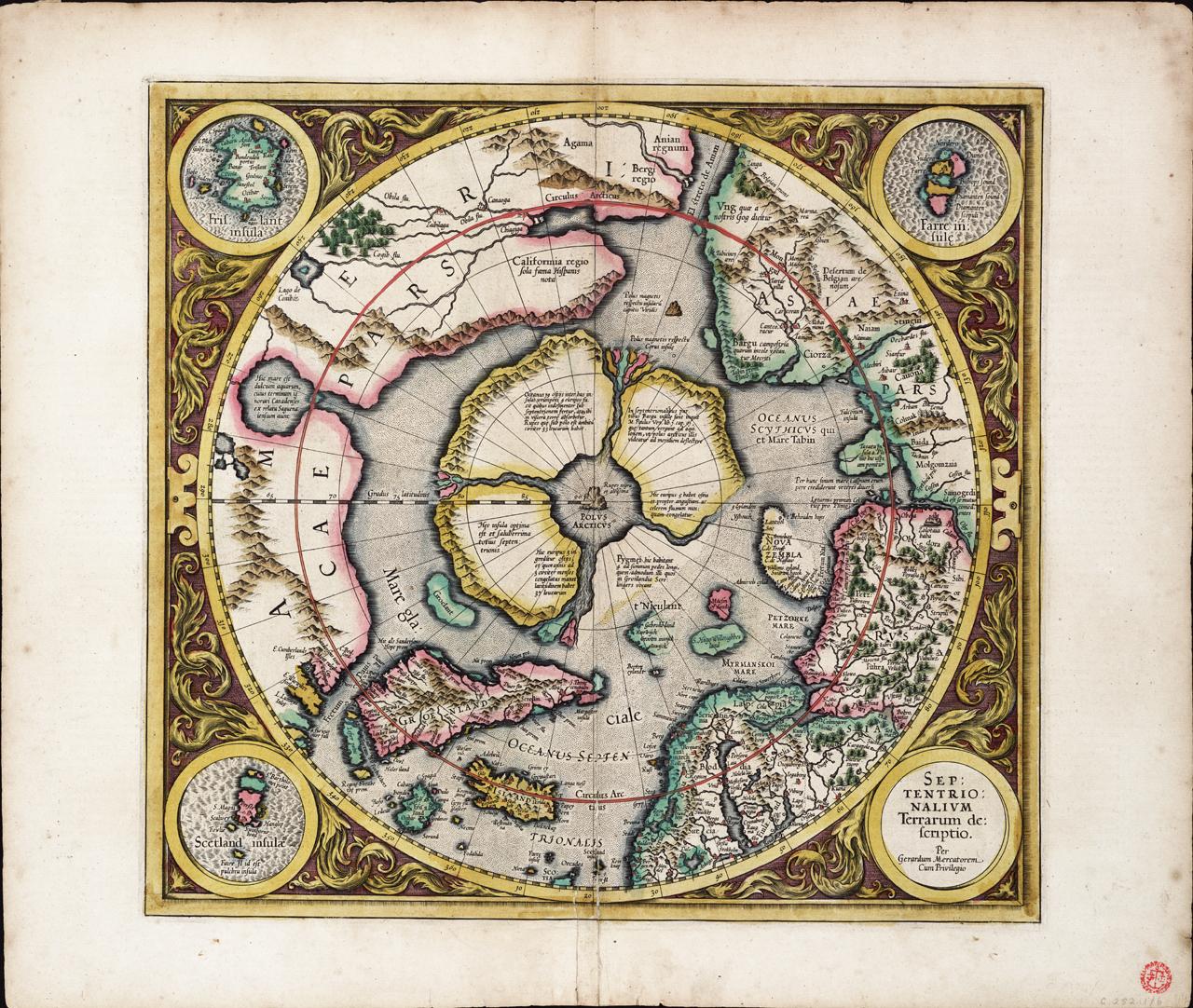

A pioneering map

From medieval monks to mythical islands, Gerardus Mercator’s map of the North Pole is the first standalone printed map of the Arctic regions. While the 16th century cartographer never visited the North Pole, he drew on numerous sources to create this map, including a now lost account from a 13th century Minorite Friar.

The map also incorporates details from Martin Frobisher and John Davis’s contemporary voyages in search of the North-West Passage – a route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic Ocean. “The English were particularly interested in the existence of a North-West Passage, to access the wealth of East Asia and the Pacific,” says Dr Megan Barford, Curator of Cartography.

At the centre of the map is a large black magnetic rock, which depicts the North Pole. Circular insets in the corners contain maps of three islands: Shetland, Farre (the Faroe Islands) and Frisland (mythical).

One of Megan’s favourite details is a small rock towards the upper right of the map. “There are various ideas about what that second rock is doing, and it might have been included to account for magnetic variation,” they explain. “Compasses don’t point due north, and that’s something we know changes over time. There’s a suggestion that having this other magnetic rock helps to explain why this is, because the magnetic field is complicated by there being this additional rock, alongside the one at the geographical North Pole.”

For Megan, this map provides a valuable insight into the transmission of knowledge during this period. “This map, at the time it was published, was a very serious contribution to European understandings of world geography,” they explain. “It’s a really interesting – as well as visually appealing – example of how different sources of geographical knowledge are brought together into a map.”

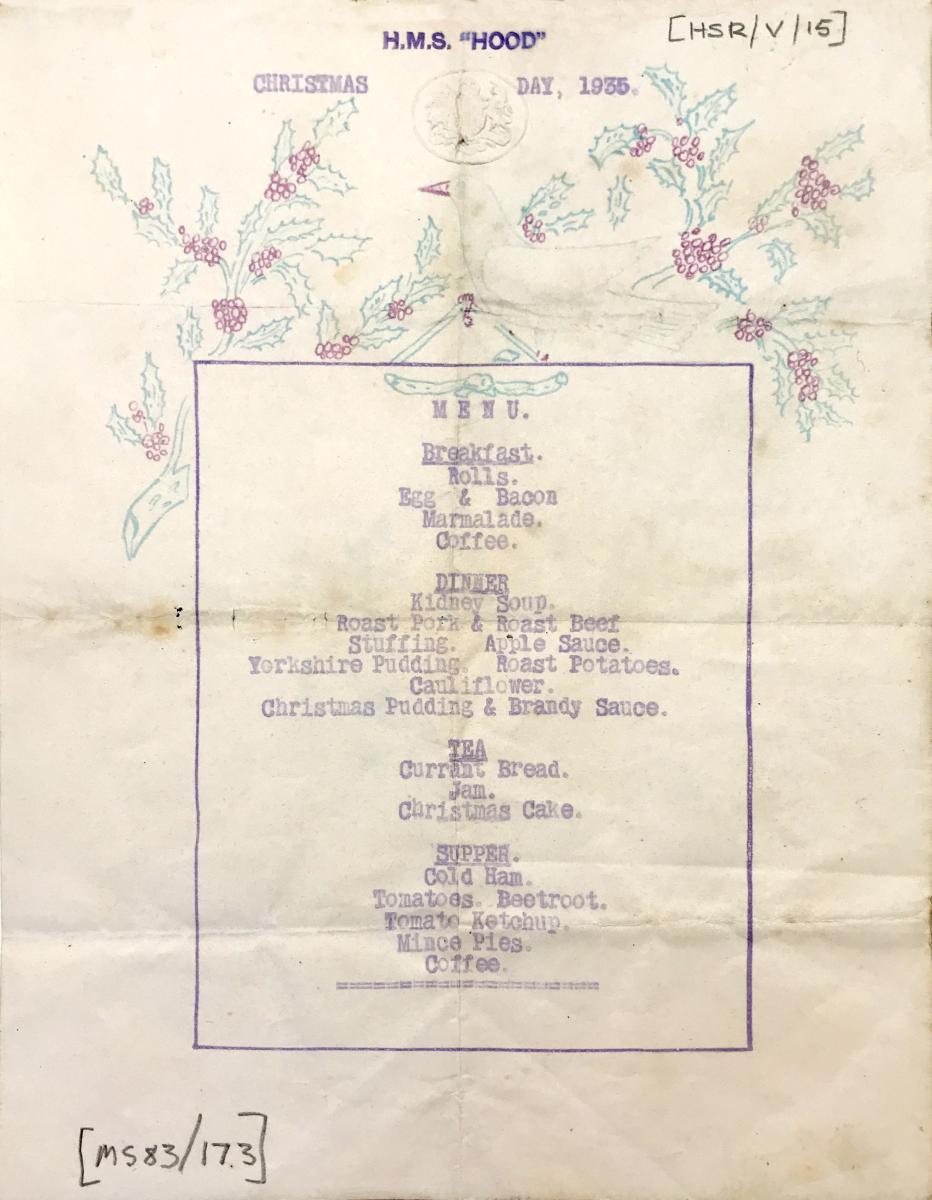

A festive feast at sea

Mince pies, roast pork and Christmas cake were just some of the festive treats served on board HMS Hood on Christmas Day, 1935.

The last battlecruiser built by the Royal Navy, HMS Hood was launched in 1918 and commissioned into service in 1920. “It was the largest warship in the world for over 20 years after its commissioning into service,” explains Alex Grover, Assistant Curator. “Because of this, it gained the nickname the ‘Mighty Hood.’

A menu within the Caird Library and Archive gives an insight into the Christmas food and drink the crew would have enjoyed. For breakfast, rolls, eggs, bacon and marmalade were available. At dinner time, the crew would have celebrated in style, tucking into offerings, including kidney soup, roast pork, roast beef, apple sauce, roast potatoes and Christmas pudding and brandy sauce. Tea included currant bread, jam and Christmas cake. For supper, the crew enjoyed cold ham, tomato ketchup, mince pies and coffee.

Aside from a cruise around the world visiting British Empire ports in 1923 and 1924, HMS Hood predominantly spent its time in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean during the inter-war years. In Christmas of 1935, it was anchored in Gibraltar. “The battlecruiser was attached to the Mediterranean Fleet and was stationed in Gibraltar during the Spanish Civil War and the Italo-Abyssinian War of 1936,” Alex says.

While the horror of the loss of the battlecruiser is still keenly felt – only three out of the 1400-plus crew survived after being hit by shells from German ships in 1941 – this menu offers a glimpse into happier times on board.

Greenwich views

This wintery study of the Royal Observatory was made by William Lionel Wyllie in the 1920s. For Katherine, Wyllie’s use of rapid sketching enhances the work’s wintery atmosphere. “The pencil lines suggest the bare branches of the trees, while the white paper becomes the snowy ground of Greenwich Park with the addition of a few shadows in watercolour,” she says. “In the background, the figures and trees have been loosely hatched in pencil.”

Dominating the foreground is the unfinished sketch of the Royal Observatory, which has been created using greys and browns. “Wyllie was good at creating a scene using only a few colours,” Katherine explains. During his lifetime, Wyllie captured many views along the Thames, and would have been familiar with Greenwich and the Observatory.

Today, more than 5,000 of Wyllie’s drawings and watercolours are in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collections – discover more of his work online.

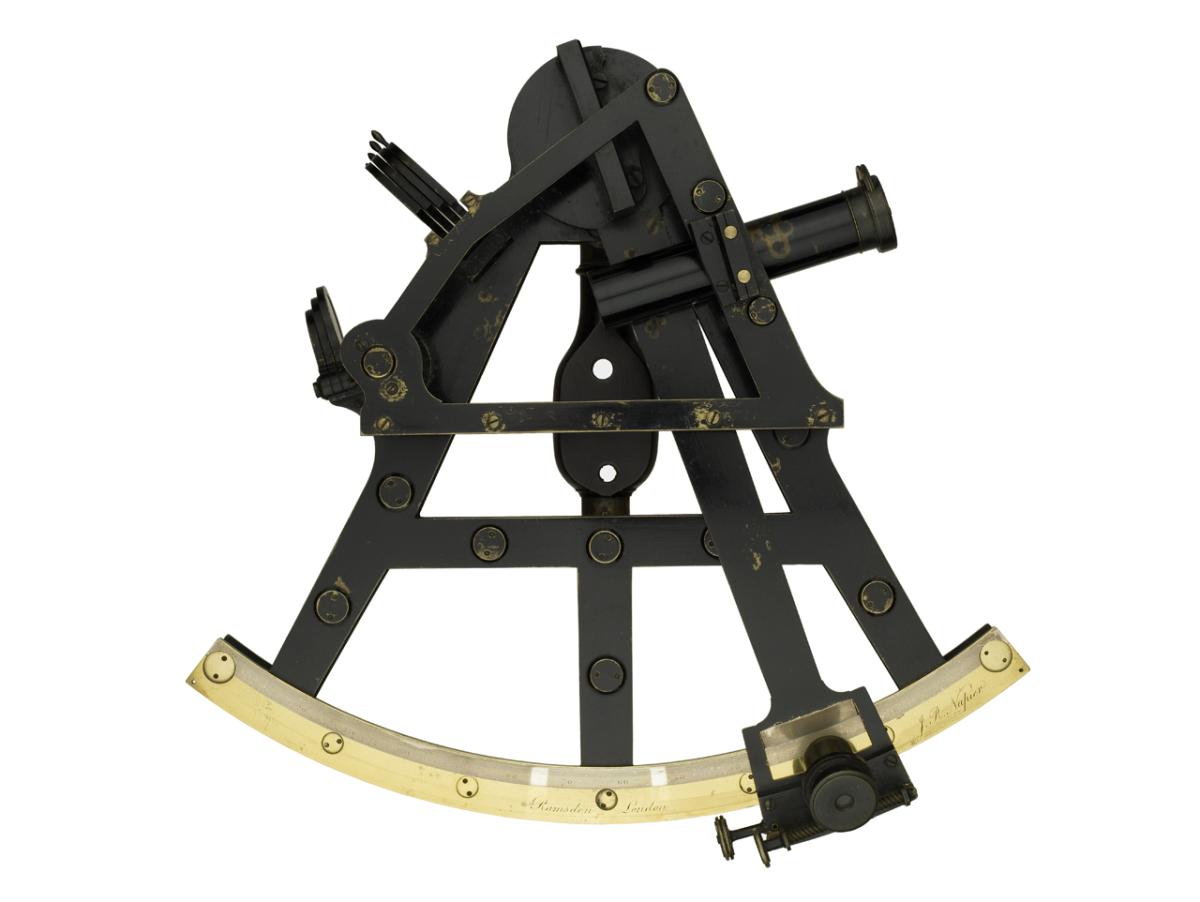

A special Christmas gift

Father Christmas is known for giving gifts to children, but what does he receive for Christmas? This double frame bridge sextant was given as a Christmas gift to Santa in the early 20th century. A circular handwritten label on the lid of the instrument contains the following inscription: ‘Helen, Francis & Gordon gave this instrument to Father Christmas 1907.’

A sextant is an instrument used for measuring angles between objects. Sextants can be used for navigation at sea, and can help seafarers to determine the ship’s location. Seafarers can measure the angle between the horizon and the Sun, to find local time and latitude. This can then be compared with Greenwich time to find longitude.

This sextant was made in around 1795 by the English instrument maker, Jesse Ramsden. It later belonged to Edgar Tarry Adams, an avid collector of navigational instruments. Adams often asked his family to give him such items for birthday and Christmas presents.

Santa’s coming!

This playful image of Santa at sea forms part of the Waterline Collection at Royal Museums Greenwich – an assortment of 16,500 photographs that tell the story of the leisure-cruising industry. Spanning from the 1920s to the 1970s, the images document life on board passenger and cruise ships, including P & O, Swedish-America Line, Canadian Pacific, Cunard and White Star.

Here, a crew member on the P & O Passenger liner, ‘Oriana’, climbs down the forward funnel, dressed as Father Christmas.