On 6 June 1944 the largest amphibious invasion of the Second World War took place.

The invasion of Normandy, or D-Day as it is popularly remembered, was an immense undertaking.

On the first day of the assault, 132,715 Allied soldiers were successfully put ashore against scattered but nonetheless heavy resistance.

The failure of German forces to prevent the landings or eject the attacking forces from their hard-won positions was a significant milestone on the road to the final defeat of Nazi Germany, which was at that time struggling to hold its crumbling eastern front against the Soviet Union and contain the Western Allies in Italy.

For Britain’s maritime forces, the efforts to make D-Day possible began long before the summer of 1944.

The first US forces began to arrive in Britain in the late summer of 1942, many of them transported by the ships of the Merchant Navy and escorted by British and Commonwealth warships. This steady build-up was sustained alongside the ongoing task of maintaining Britain’s maritime lifeline.

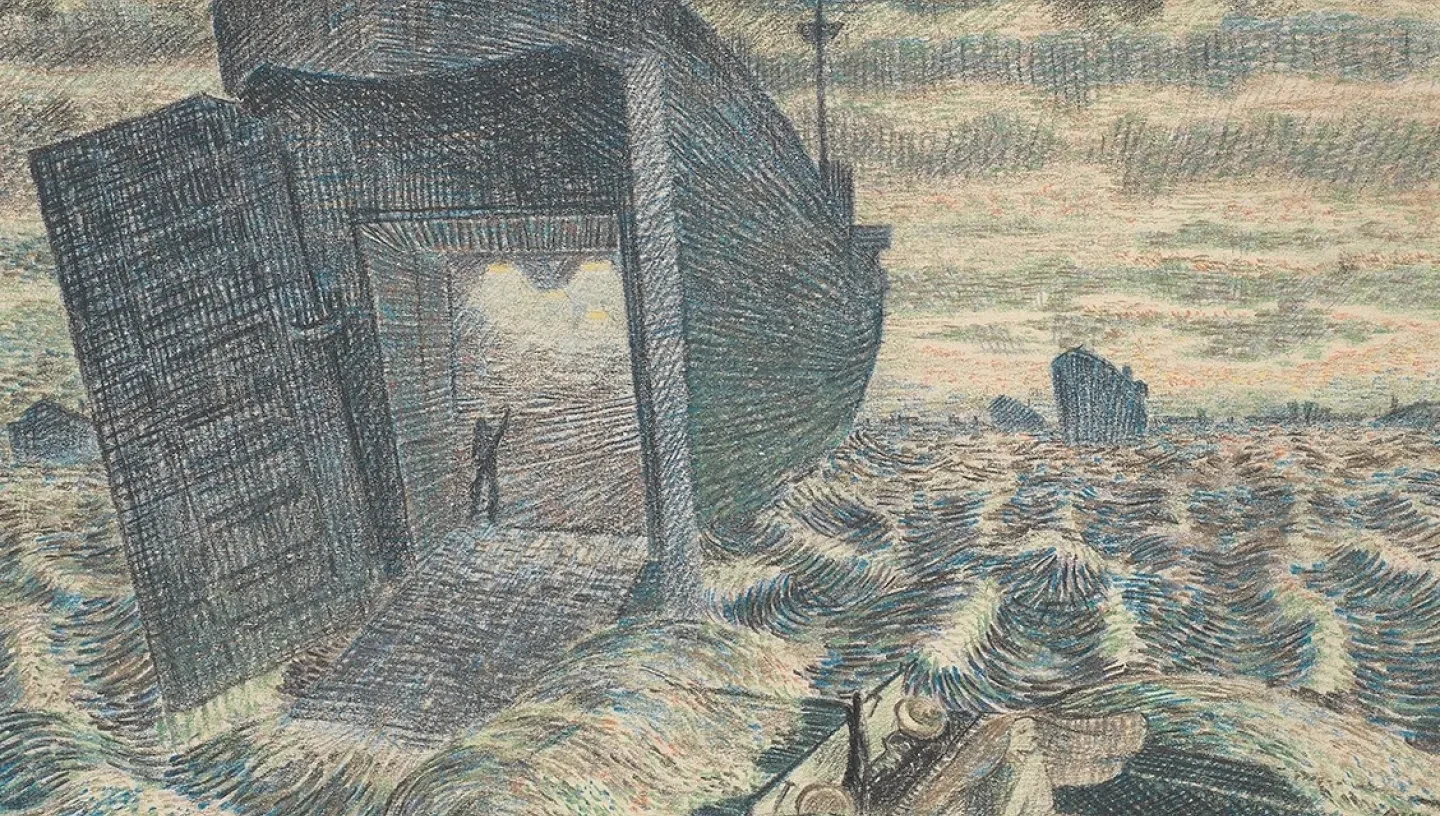

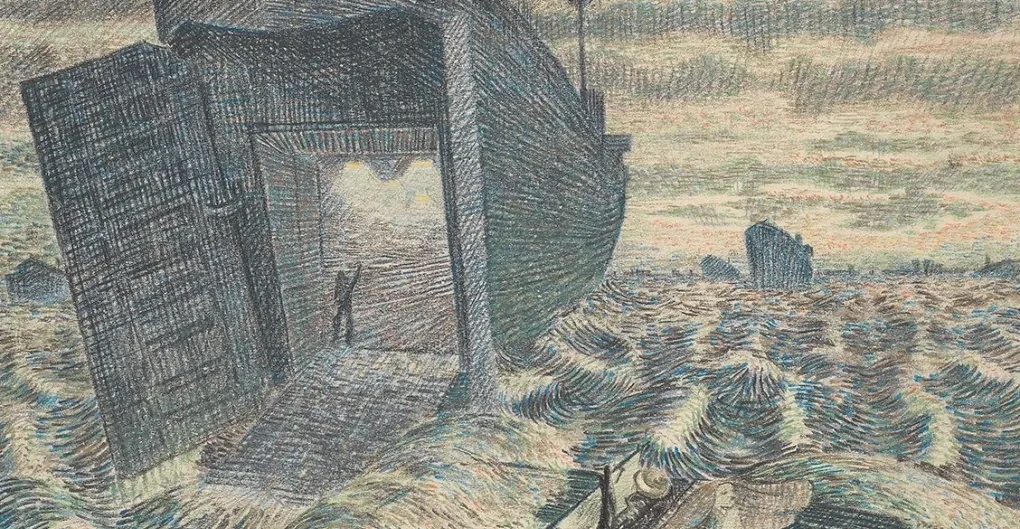

As the date of the invasion drew close, the naval duties expanded to include mine clearance and perilous surveys of the selected landing beaches. To preserve operational secrecy the latter task had to be carried out by midget submarines. A small number of these craft were the first Allied warships to arrive on station on the morning of 6 June, their role to guide the landing forces in with signal lights.

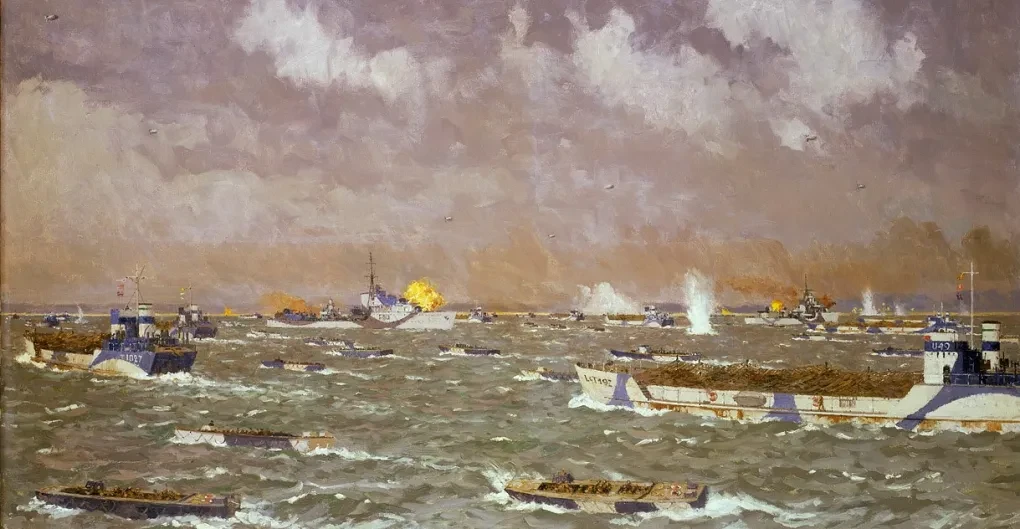

With the main strength of US naval forces committed to the Pacific, the task of protecting the vast assemblage of invasion ships fell primarily to the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy.

The bare numbers of vessels involved are an indicator of the sheer complexity of Operation Neptune. Including the amphibious landing vessels, the Allied forces brought almost 7,000 ships across the channel. Of this total, 1,213 were warships charged with protecting the vulnerable transports and providing firepower to soften up the German defences. The British and Canadian contribution in warships totalled 958, ranging from small minesweepers to the 44,000-ton battleships HMS Nelson and HMS Rodney.

Naval gunfire support proved an essential ingredient to the success of the landings, as it allowed troops on the ground access to a level of sustained firepower that could not be matched by German artillery. Even with its ‘X’ turret out of action from damage sustained in the Mediterranean, the battleship HMS Warspite could still put out a weight of metal roughly equivalent to that of a British artillery division.

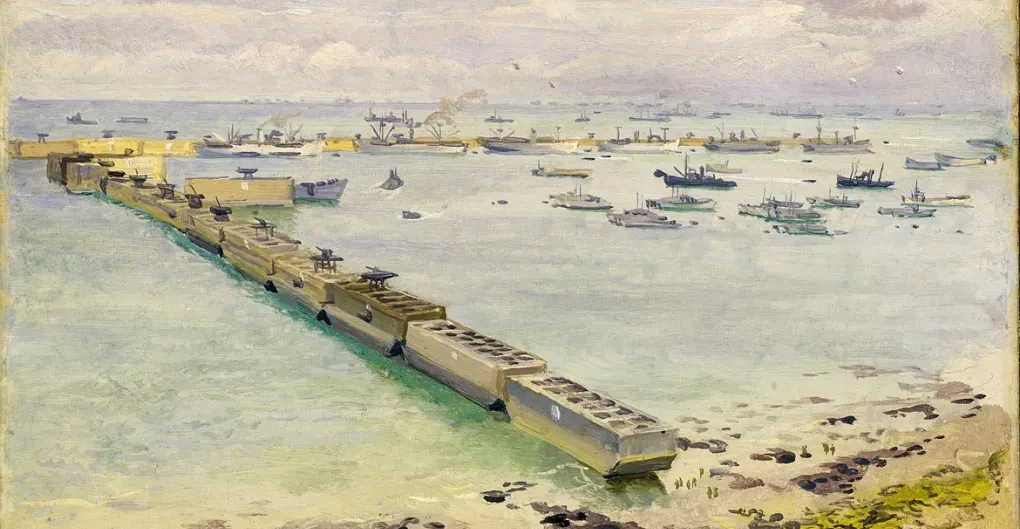

The demands of Operation Neptune did not end with the securing of the five invasion beaches on the first day. There still remained the task of completing the PLUTO oil line and the essential ‘Mulberry Harbours’. These were necessary to sustain Allied soldiers ashore until a functioning port could be secured. The destruction of one of the artificial harbours by bad weather on 19 June was a sobering illustration that the Germans were not the only enemy the seamen had to be concerned with.

The naval presence was maintained in strength until the end of June, when it was deemed reasonably certain that the German naval and air threat was diminished. For the Merchant Navy, the huge logistical task of keeping the Allied armies supplied and reinforced continued until the end of the War.

The scale of their contribution can be measured by another examination of some relevant figures. By the end of June 1944 Allied ships had landed 850,279 men, 148,803 vehicles and 570,505 tons of supplies. The sobering price of this success was 50 ships sunk and a further 110 damaged to varying degrees.

Andrew Choong is Curator of Historic Photographs & Ship Plans at Royal Museums Greenwich