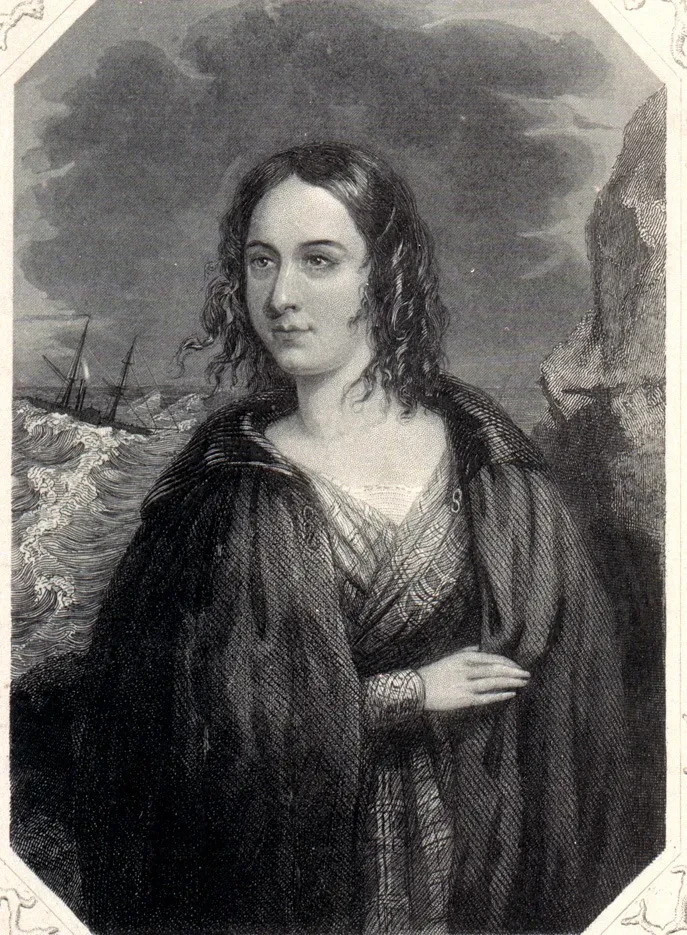

Grace Darling achieved great fame for the part she played in the rescue of survivors from a wrecked merchant ship in 1838.

Born in 1815, Grace heroically helped to rescue survivors from the Forfarshire, a vessel travelling from Hull to Dundee, which was wrecked on the Farne Islands, off the coast of Northumberland.

Who was Grace Darling?

The daughter of a lighthouse keeper, Grace was born in Bamburgh on the mainland on 24 November 1815. She spent nearly all of her life on the Farne Islands, scrambling about with her eight siblings, of which she was the 6th, and being taught to read and write by her parents. Grace shared in her father William’s fondness for music, history, geography and Christianity.

By most accounts it was a happy childhood, with Grace helping her mother with the housework and her father with the duties of Lighthouse keeping, including cleaning and lighting lamps. For this she received a £70 a year salary from Trinity House, as well as bonuses for help with rescuing and salvaging shipwrecks.

It was a lonely, but enjoyable life for a child said to have had a love of the outdoors. By the age of 22 there’s no doubt that a young woman like Grace would have known how to handle a boat.

She is remembered for saving the lives of nine people from a shipwreck in 1838 - The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography even lists her as ‘Grace Darling, heroine.’

The wreck of the Forfarshire

Grace’s father, William, was keeper of the Longstone Lighthouse on one of the islands. On the evening of 7 September 1838, while looking out of an upper window of the lighthouse during a raging storm, Grace spotted the wreck and survivors of the Forfarshire. The paddle-steamer was carrying around 40 cabin and deck passengers and had completely split in two on a rocky outcrop of the islands, known as Big Harcar. The heavy winds, rain and waves battered the stricken vessel. Grace's actions would cause a sensation that gripped the nation, inspiring a generation and bringing unprecedented fame.

Besides Captain Humble and his wife, there were 61 people on board the Forfarshire.

On her previous voyage, the Forfarshire had experienced boiler trouble, so before leaving Hull a local firm of marine engineers were paid to close a small leak in the centre boiler.

However, as she began her trip up to Dundee, the starboard boiler began to leak. Alan Stewart, the chief engineer organised two pumps to be set up to remove water from the hull and refill the leaking boiler. This was in vain; the leak was so bad that the Forfarshire lost power and speed.

Instead of putting the ship in for repairs at the nearest harbour, Captain Humble pushed on and passengers were pressed into service at the pumps, as water leaked uncontrollably from the boiler into the hold.

As the ship battered up the Northumberland coast, the boilers finally gave way and the engine stopped. With the engines out, sails were set on the two masts, usually reserved for emergencies or auxiliary power on these early steam vessels.

As the weather deteriorated and without power, Captain Humble turned the Forfarshire back to the south, maybe to try to find safety behind the Farne Islands off Northumberland.

The Farne Islands are an outcrop of around 20 rocky islands rising up out of the water just over a mile from the mainland. The number of islands depends on the tide, making it a particularly dangerous place for ships. Between 1740 and 1837 there were 42 ships recorded as having been wrecked at the Farne Islands.

Trinity House, the organisation responsible for the provision and maintenance of navigational aids was aware of the dangerous nature of the site and installed two lighthouses on the islands. The first, the Inner Farne Lighthouse was built on the innermost island in 1811. The second, where Grace's father worked, was built on Longstone Island, the most seaward island, in 1826.

As the Forfarshire headed towards the islands on that stormy night it is possible that Captain Humble mistook the two lighthouses and thought the ship was safely between the mainland and the innermost island. Exactly what Captain Humble intended will never been known as he was swept over board and drowned. The ship ran aground on the rocks on Big Harcar island.

Rescuing survivors on the Forfarshire

On that fateful September night in 1838, Grace could see the wreck of the Forfarshire being beaten by the waves. With her siblings away, Grace and her parents were the only people at the Lighthouse.

Grace and her father thought it would be too rough for the lifeboat to set out from the nearby village of Seahouses, so they decided they would have to row their own small boat across to help the survivors.

It is sometimes claimed that Grace pleaded with her reluctant father to embark on the rescue, but this is unlikely. What is clear is that they both would have known the risks of heading out in a small boat in those conditions, and neither could have done it alone.

Grace later wrote:

I was the first that saw the Distressing affair and amediately acquainted my father…. I was very anxious and did render every assistance that lay in my Power but my Father was equally so and needed not to be urged by me he being so Experienced in such things.

As they launched their small boat the strong winds meant they were forced to keep to the more sheltered side of the islands, which meant they had even further to row – a distance of nearly a mile.

As the Forfarshire had run aground, the waves beat mercilessly against her, breaking her in two. The stern half sank, drowning nearly all of the passengers at the back of the ship, except for a few who managed to escape on a lifeboat.

The forward end of the ship had stuck fast to the rock, and twelve of those that were at the bow of the ship - seven passengers and five of the crew remained clinging perilously to the wreck.

As the tide went down the survivors managed to get off the wreck onto the rocky island. Three of the passengers died of exposure, two children and the Reverend John Robb. The only surviving woman, Sarah Dawson, was still clinging to her two dead children as Grace and her father reached the island.

Grace steadied the boat while her father helped four men and Sarah Dawson into the boat. William and two of the rescued men rowed back to the lighthouse, where Grace looked after the survivors. Her father and the three men returned to save another four survivors.

The Forfarshire had been carrying 63 people and Grace and her father saved all of the 9 still alive on the Harcar rock.

William Darling wrote a rather restrained report to Trinity House explaining the events of that night. Within it he comments that they would only have been able to return if there were survivors strong enough to help them:

We agree that if we could get to them some of them would be able to assist us without which we could not return; and having no Idea of a Possibility of a Boat coming from North Sunderland, we amediately launched our Boat, and was Enabled to gain the rock where we found 8 men and 1 woman, which I judged rather too many to take at once in the state of the Weather; therefore took the Women and four Men to the Longstone; two of them returned with me and succeeded in bringing the remainder, In all 9 persons, safely to the Longstone about 9 o’clock

Once back at the Longstone lighthouse, the survivors were cared for as best they could with limited resources, having to remain on the island until the weather calmed.

Those who had abandoned ship in the lifeboat were picked up the next day by a sailing vessel.

Grace Darling, a Victorian heroine

Grace was in almost every newspaper in Britain, both local and national and she was showered with honours. These included the Royal National Lifeboat Institution's Silver Medal for Gallantry and the gold medal of the Royal Humane Society. Her fame even prompted a donation of £50 from Queen Victoria. There were numerous visitors to the Longstone, all hoping to catch a glimpse of the heroine.

The objects connected to Grace took on an almost cultish or religious quality in the eyes of her admirers. They became relics for veneration. Her story was the topic of many ballads and she entered the wider folk tradition of the nation and in the nascent consumer capitalism of Victorian Britain her image and name was even used to sell soap.

Context

To understand Grace's fame, it is necessary to take into account the historical context of the time. It was a time of great progress and excitement in Britain and the Empire. Steam powered travel was just taking off, a young queen had ascended to the throne the year before, and despite some major unrest amongst the working class, Britain was entering a period of peace and prosperity.

However, the advances in technology did not result in a reduction of the dangers of sea travel. The increasing number of shipwrecks after the introduction of steam power meant the nation was gripped by a sense of panic at the number of deaths that occurred at sea. In 1836 a Select Committee of the House of Commons into the ‘Causes of Shipwrecks’ reported that between 1833 and 1835 there were 1, 573 vessels stranded or wrecked, and another 129 lost or missing.

Within this context Grace was a young woman was doing her bit to help, and someone people of all classes could rally around.

The Newcastle Chronicle declared:

This perilous achievement stands unexampled in the feats of female fortitude. From her isolated abode… she made her way through desolation and impeding destruction… to save the lives of her fellow beings.

The Times asked:

Is there in the whole field of history, or fiction even, one instance of female heroism to compare for one moment with this?

Heroism and gender

Grace’s actions were viewed as remarkable as they were unusual for her gender. Her brother would have been in her place had he not been away. Showing courage and risk-taking were viewed as particularly masculine traits. It was also considered quite a feat for Grace to steady the coble next to the rock as her father climbed out to get to the survivors. Women were associated with beauty, not strength. Many who met her were surprised by her appearance, expecting her bold actions to be matched by manly features. The Mercantile Gazette reported:

‘She is not the amazon that many would suppose her to be, but as modest and unassuming a young woman as you can imagine’.

Yet at the same time, the rescue was used to promote an ideal femininity. It was interpreted to support the view that women are care-givers. As Florence Nightingale became ‘the lady with the lamp’, in a similar vein Grace Darling was pictured with her coble. The historian Hugh Cunningham argues that these symbolic images helped to reinforce separate gender spheres. While men went to war, and made money, women performed pure and worthy deeds such as saving lives.

She remained famous throughout the 19th century and in 1938 a Museum dedicated to Grace and seafaring in the region was founded at her birthplace, Bamburgh. In 2004 she was voted Northumberland's top woman.

Adding to her appeal is the way Grace herself didn’t embrace her fame or seek fortune through it; instead she sat for a number of portraits, and answered as many letters as she could from her numerous admirers both male and female. It was noted that she was rendered almost bald by the number of requests for locks of her hair!

Parts of her story were even exaggerated, with some entirely made up. The first four books about Grace were fictionalized accounts. They romanticised her actions, making them more appealing to a sentimental early Victorian public.

For example, Jerrold Vernon’s novel, Grace Darling or the Maid of the Farne Isles (1839), imagined aspects of Grace’s childhood to emphasise her sweet and dutiful nature. Myths developed that Grace had persuaded her father to go out in the coble against his better judgement and that she had heard the cries of the survivors from the lighthouse.

Images also played a significant role in shaping perceptions. One of the most famous was by Thomas Brooks, depicting Grace alone in the boat. She has a look of determination on her face, as she strongly grips the oars. The painting was intended to show the moment after William stepped out onto the rock, but it helped create the legend that Grace rowed out alone.

See the Grace Darling figurine in the Sea Things gallery at the National Maritime Museum

She never married, despite numerous requests but instead remained at the Longstone Lighthouse to assist her mother and father.

In 1842 she was taken ill on a visit to the mainland, after a short period of deteriorating health she died of tuberculosis in October 1842. She was buried at St. Aidan’s churchyard in Bamburgh.

Her death served only to cement her fame and she remained forever the infallible young woman of the rescue.

Banner image: Wreck of the 'Forfarshire, 7 September 1838 by T L Leitch