The Great Plague

Bubonic plague terrorised Europe for centuries. In 1665 a devastating epidemic struck this country killing thousands of people.

Officially the ‘Great Plague’ killed 68,595 people in London that year. The true figure is probably nearer 100,000 or one-fifth of the city’s population.

Bubonic plague did not arrive in London suddenly in 1665. For over a year, reports of cases had been talked about endlessly. The wealthy increasingly avoided the city and might very well survive an outbreak.

For the poor escaping London was more difficult and the cramped and filthy conditions in which many lived encouraged the spread of the disease. Any house where plague was identified was supposed to be shut up for 40 days with the family inside, marked with a cross and guarded by watchmen. Fear of being locked in with the dying meant that many early cases of plague were kept quiet.

Symptoms

Symptoms of bubonic plague included:

- fever

- delirium

- painful swellings of the lymph nodes in the neck, armpits and groin (‘buboes’)

- vomiting

- muscle cramps

- coughing up blood

Plague usually resulted in death, normally within a week of the first symptoms. The first few days though were without symptom and someone fleeing the dead could be a good carrier.

London during the Great Plague

The peak of the epidemic was the week of 19–26 September 1665 when London mortality bills recorded 7,165 deaths from plague. London now appeared almost deserted during the day. Grass grew on the streets of Whitehall and the court fled London for Oxford. In the City, the keeping of dogs, cats, and other domestic animals was banned and the dog-catcher destroyed over 4,000 dogs. Boats no longer sailed on the Thames and the Navy wisely kept its ships away from London.

Night after night, porters took piles of corpses for burial, filling large pits with the dead. Adding to the horror were rumours of the bereaved and the ill throwing themselves into the pits alive.

‘I having stayed in the city till above 7400 died in one week, and of them above 6000 of the plague, and little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells; till I could walk Lombard Street, and not meet twenty persons from one end to the other … till whole families (ten and twelve together) have been swept away … till the nights (though much lengthened) are grown too short to conceal the burials of those that died the day before’

Samuel Pepys, letter to Elizabeth Lady Carteret, 4 September 1665

Plague deaths rose rapidly in the spring of 1665; by June a quarter of deaths recorded in London were attributed to the plague, by August this figure had risen to 75%.

By early 1666 the number of people dying from the plague was receding and the epidemic was all but over by the summer of 1666.

The last reported case of the plague in London was in 1679. Although no one knew it at the time, this would mark the end of the era of plague that had devastated populations across Europe from the 14th Century.

What caused the plague?

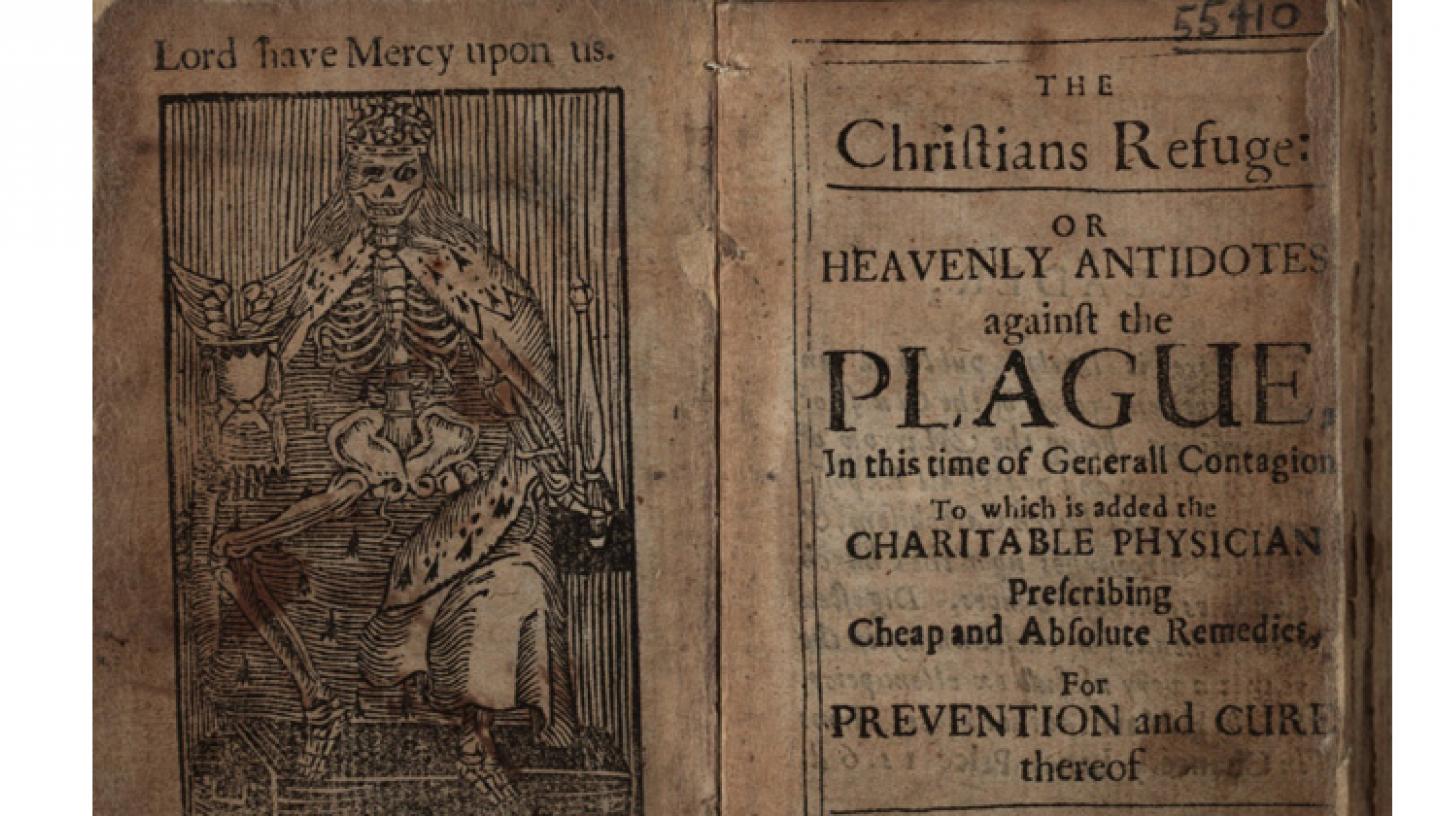

In the aftermath of the Civil War and the religious conflicts of the time, people were quick to point the finger at who or what they thought was to blame for plague.

Some looked to the alignment of the planets or the ominous appearance of a comet in December 1664 to explain the epidemic.

Medical folk discussed the transmission of the illness through bad smells. There was a good trade in nosegays and pomanders stuffed with medicinal herbs, and a proposal to float a ship of peeled onions down the Thames to counter the evil odours was entertained. Some people put their faith in amulets and charms or, like Samuel Pepys, chewed tobacco to ward off the plague:

‘I was forced to buy some roll tobacco to smell to and chaw – which took away the apprehension.’

Samuel Pepys, 7 June 1665

The plague was actually caused by infected fleas carried by black rats, although this would not be known for centuries to come. Rats were particularly prevalent in the cramped and dirty streets of the capital occupied by the poorest residents.

Explore the Great Plague further in our fact-packed infographic