150 years ago, HMS Challenger departed England on a quest to explore the world's oceans.

How was this Royal Navy warship adapted and prepared to conduct ocean science around the world? And how did the ship's design help scientists and seafarers work effectively together? Find out with Dr Erika Jones, author of The Challenger Expedition: Exploring the Ocean's Depths.

The progress of oceanography depends on a great extent upon the development of mechanical aids, by which we mean not only the scientific instruments employed, but also the whole arrangements of the ship itself.

John Murray

Preparing to travel round the world

The Challenger Expedition was several years in the making.

The expedition’s civilian scientists, Charles Wyville Thomson and William Benjamin Carpenter, had both undertaken voyages on a smaller scale in the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean in the late 1860s. In 1871 they conceived ‘of the idea of a great exploring expedition that should circumnavigate the globe’, aiming to ‘find out the most profound abysses of the ocean, and extract from them some sign of what went on at the greatest depths’.

In order to realise their ambitions, they first had to convince the Admiralty to dedicate a ship and crew that could withstand the rigours of working for months at sea, and the government and Royal Society in London to provide everything else.

The Royal Society formed a committee to appeal for funding from the government. It asked for three provisions:

- A ship of sufficient size to afford accommodation and storage-room for sea-voyages of considerable length and probable absence of four years.

- A staff of scientific men qualified to take charge of the several branches of investigation.

- A supply of everything necessary for the collection of the objects of research, for the prosecution of the physical and chemical investigations, and for the study and preservation of the specimens of organic life.

These were not modest requests, but the Admiralty did approve, and Thomson and Carpenter’s plan began to form.

The transformation of HMS Challenger

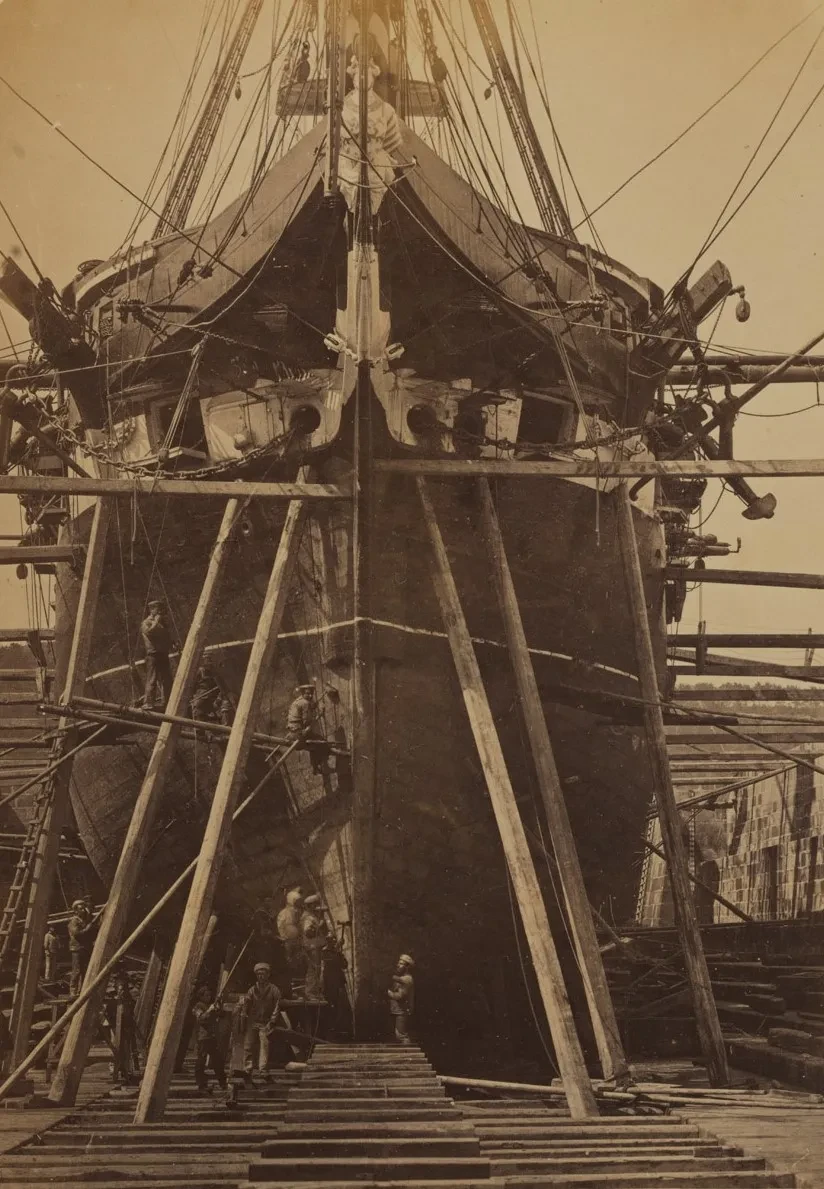

First launched on 13 February 1858 from Woolwich Dockyard, HMS Challenger was one of ten warships of the Pearl class of 21-gun corvettes and built to carry a normal complement of 290 men.

It was representative of a new maritime age belonging to steam and iron, and combined more traditional sail technology with the advantages offered by steam propulsion: the ability to travel independently of the wind, and superior flexibility of course and speed.

In March 1871, Challenger returned to Britain from its service as flagship of the Australian Station. The ship's physical attributes appealed to the expedition’s needs; at a length of 226 feet (68.9 metres) overall, 200 feet (61 m) on deck and with a beam of 40 feet 6 inches (12.3 m), the ship had ample space below deck for scientific work.

Challenger was selected for the expedition and its 14-year service as a warship came to an end.

In preparation for the circumnavigation, the ship’s refit commenced in June 1872 at Sheerness Dockyard, located at the mouth of the River Medway. It was estimated that repairs and modifications would require six months of planning and work.

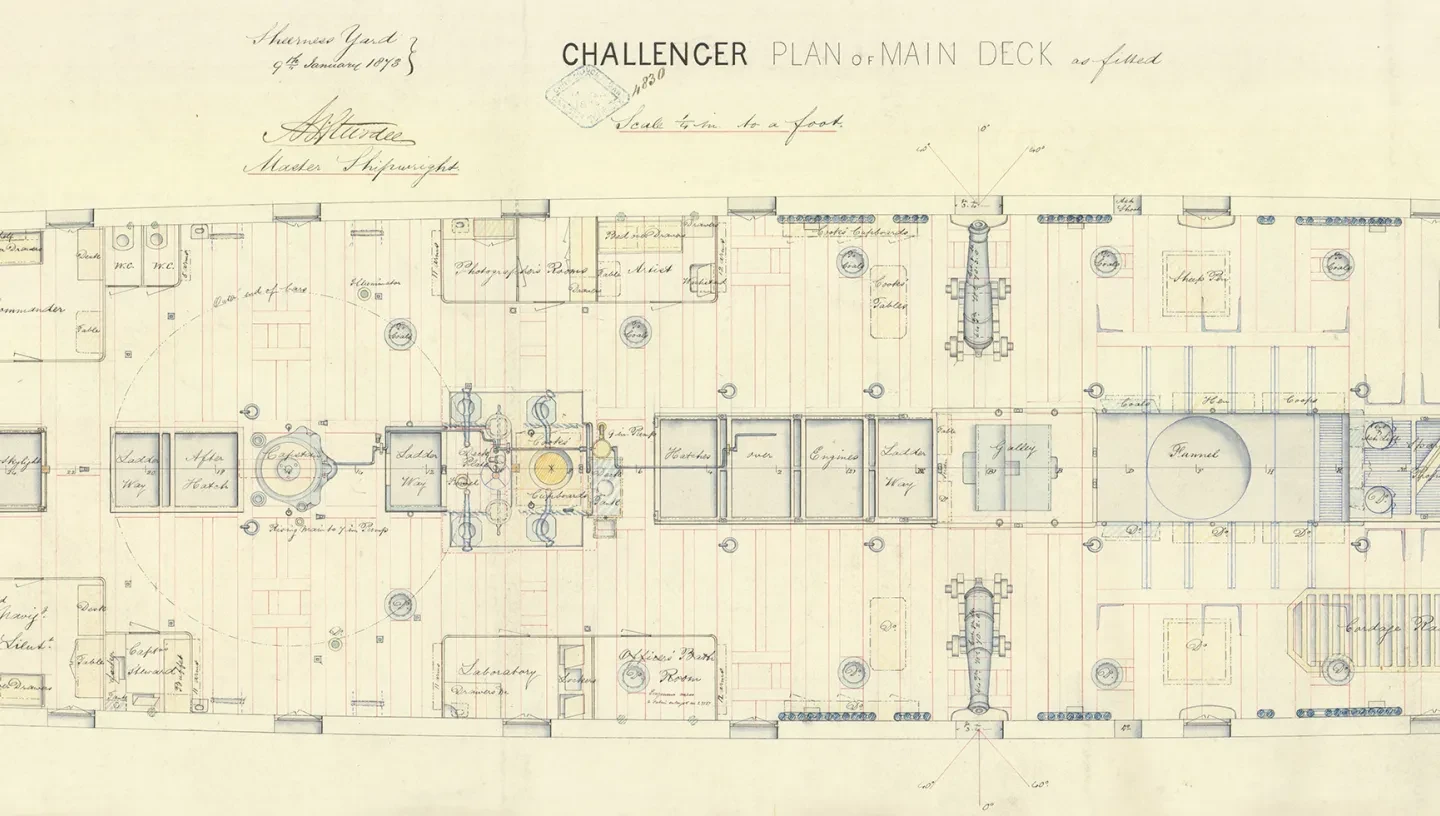

Making space for science at sea

At the time, it was unusual for civilian scientists to live and work on naval vessels alongside the crew.

Some feared that it would be difficult for the two groups to work amicably together, especially over the course of such a long voyage. The oceanographic experiments also needed to be incorporated into the everyday operations of the vessel. For these reasons, parts of the ship were adapted and others were radically altered in preparation for the expedition.

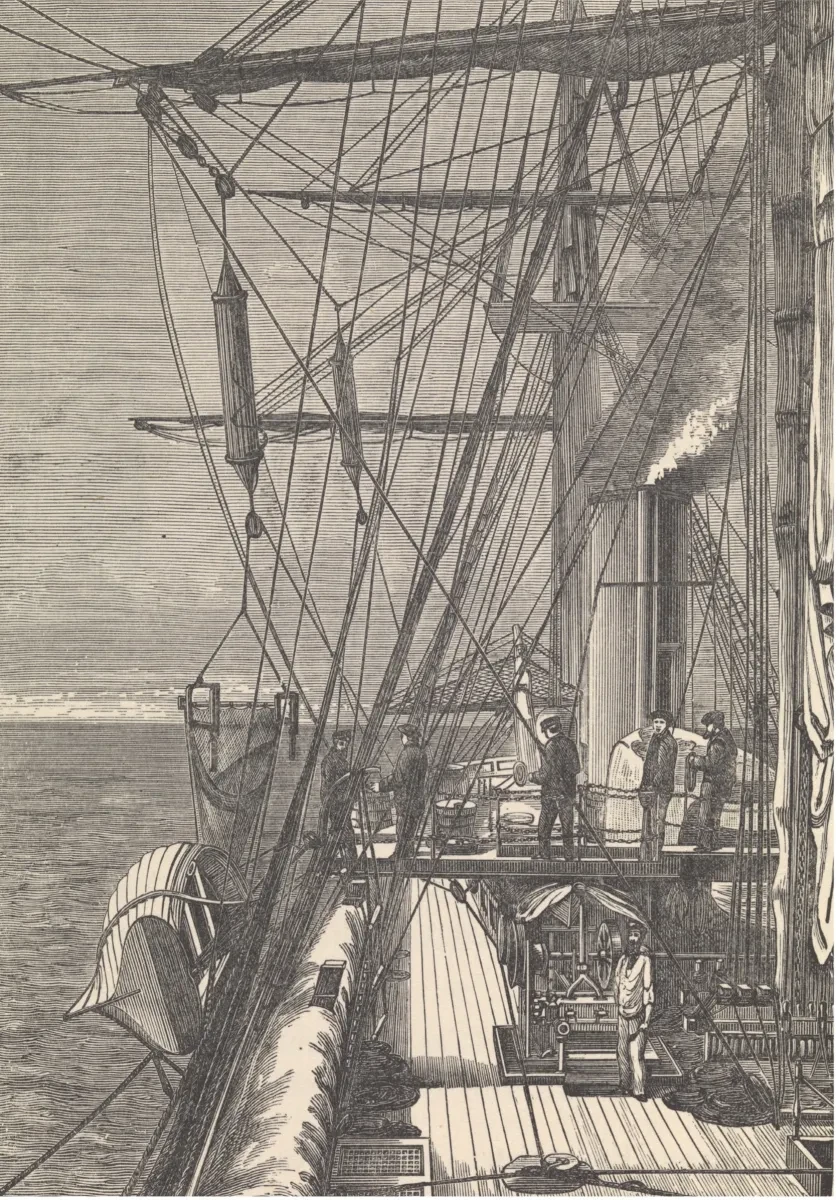

Dredging was central to the naturalists’ study, but the sorting process deposited large quantities of mud on the ship’s deck. A raised dredging platform (pictured) was therefore installed in front of the mainmast in the central part of the ship and built level with the hammock nettings.

There, ‘the contents of the dredge might be emptied, so that the naturalists, while engaged in sifting the mud and preserving specimens, might not be interrupted by the seamen working the ropes’.

Two large shafts were fitted from the platform to the water’s edge so that ‘the refuse from the dredge might be thrown overboard without dirtying the decks’.

Below the platform, lengths of line dominated the upper deck, ‘reeled and coiled in every available spot on the forepart of the main-deck and elsewhere’, used in sounding, dredging and measuring ocean temperatures. A small steam engine on the upper deck aided with the hauling of the line and instruments back to the surface.

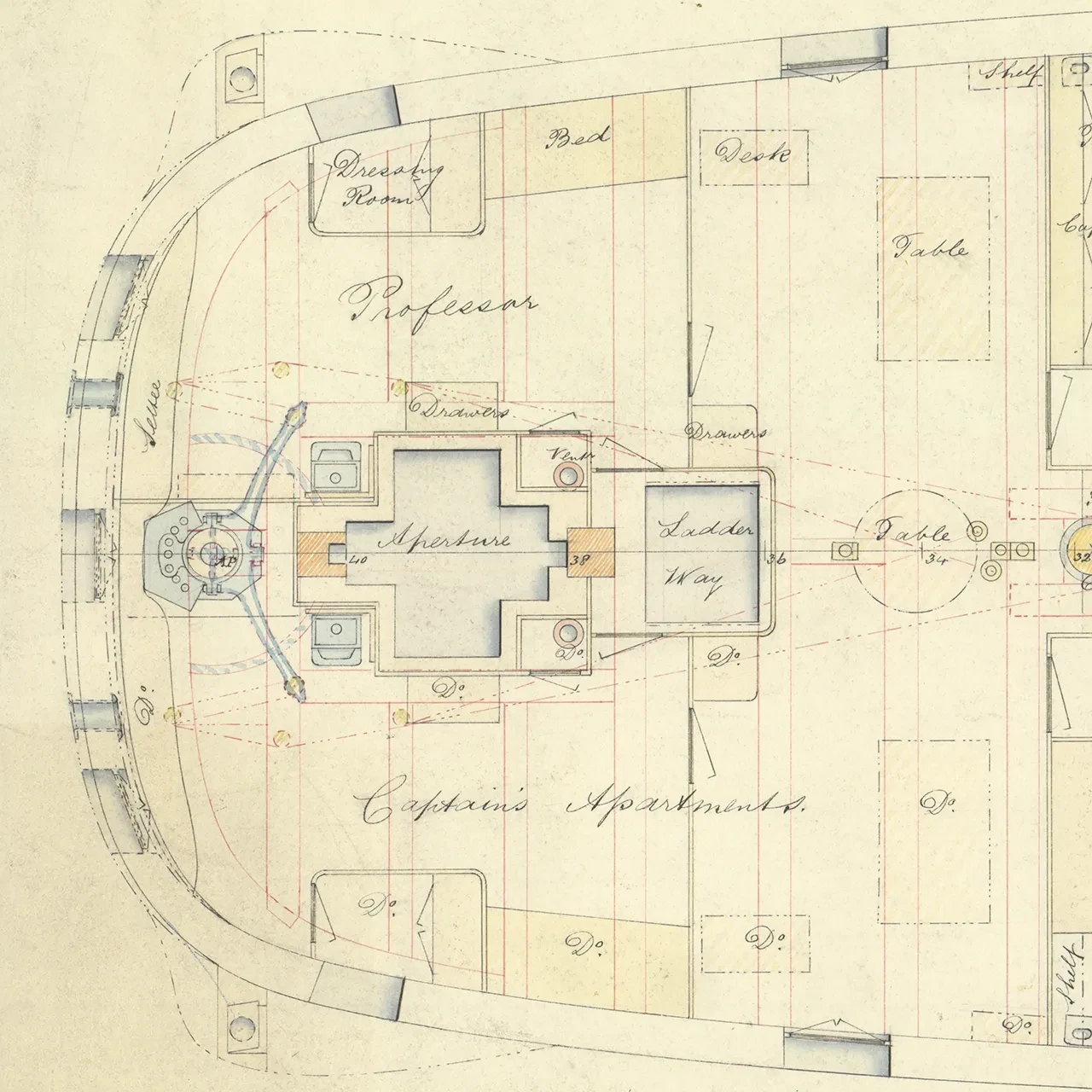

In Challenger, unusually, two cabins of equal size were built, one each for Captain Nares and Thomson – a statement of the professor’s position of authority on board.

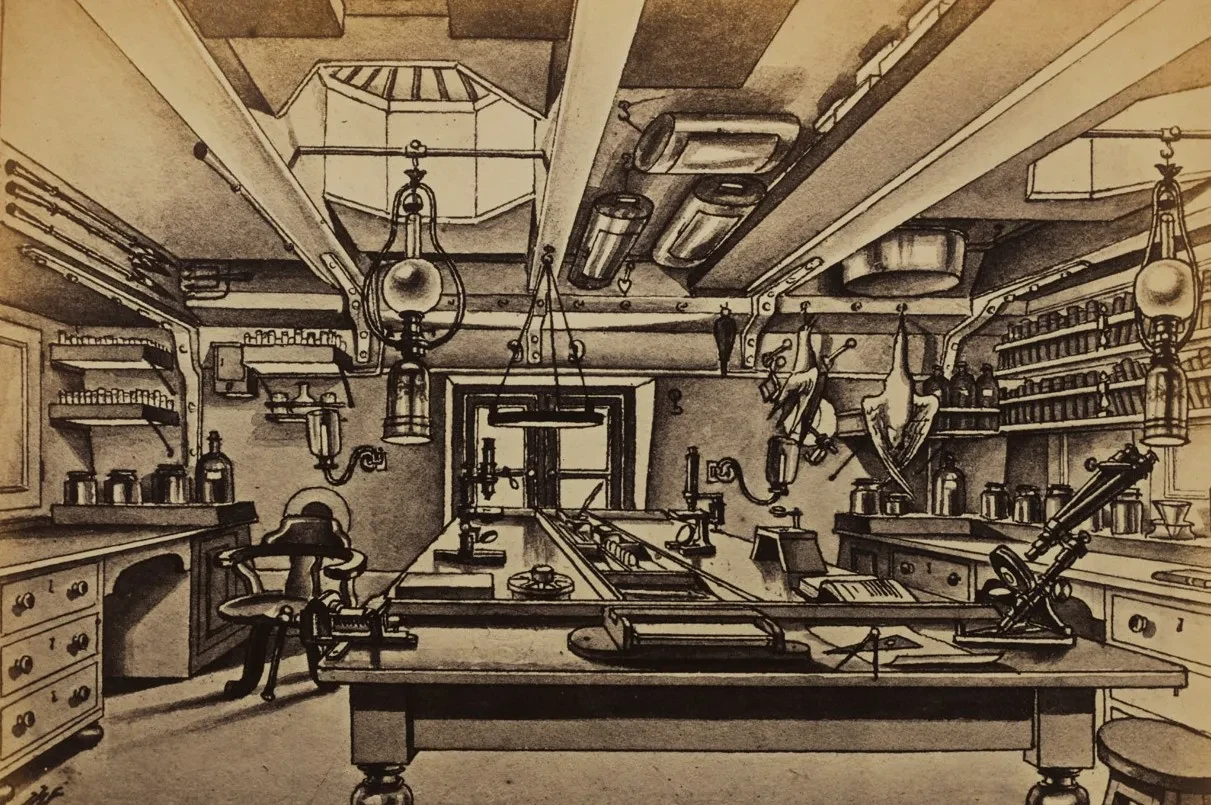

In place of a battery of guns were laboratories, workrooms and storage for marine specimens. Two large workrooms (measuring 18 feet by 12 feet) were built outside the captain’s cabin, one on each side of the ship.

On the port side, the natural history workroom was prepared with many of the instruments Challenger scientists would have used in a museum or university laboratory. Modifications were made to counter the movements of a rolling ship: racks of test tubes were fitted against the walls to prevent breakage; equipment – scissors, forceps and scalpels, for example – was stored in small compartments in dresser drawers to stop it knocking about and becoming blunt; two microscopes were secured with clamps to a long workroom table to keep them upright at sea.

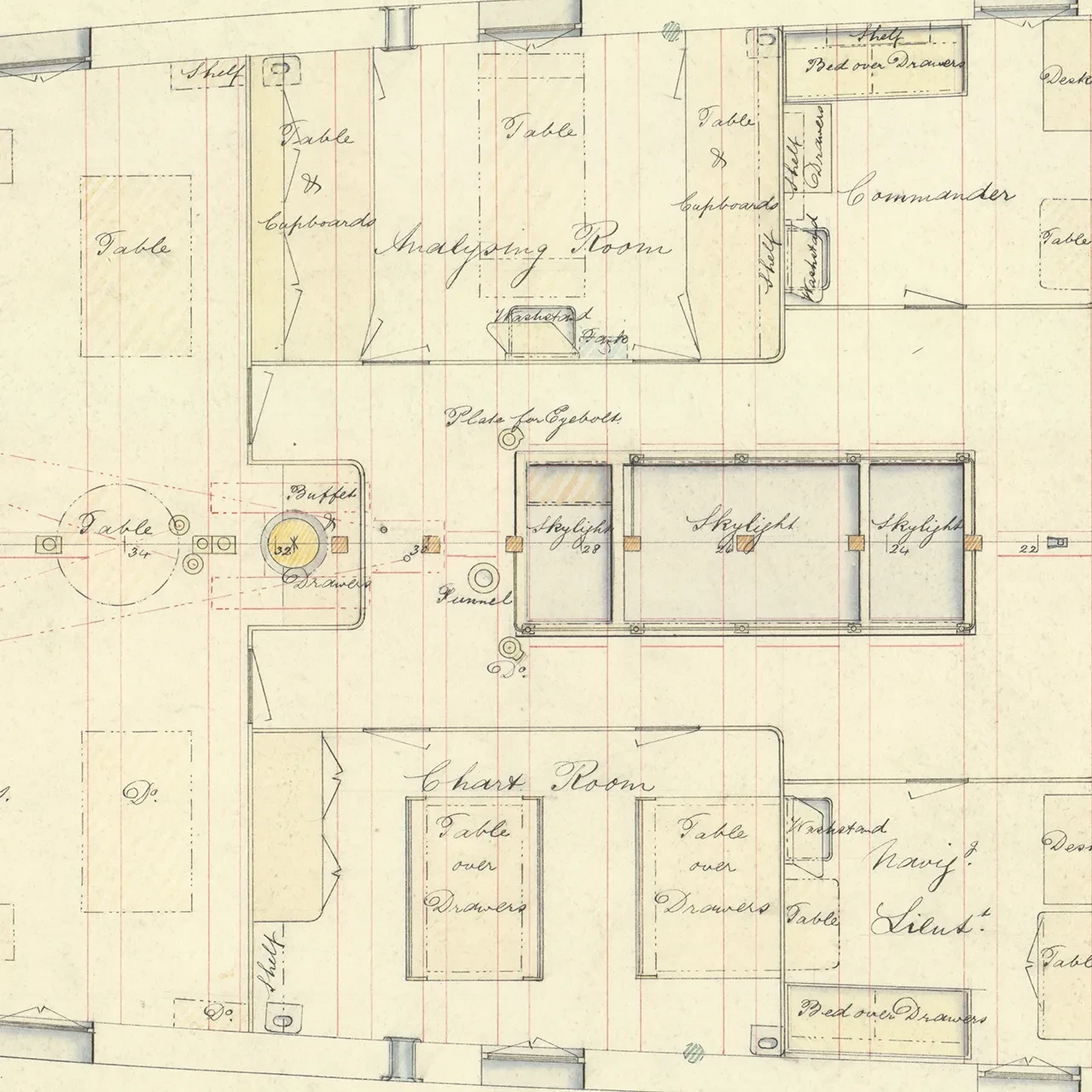

The cabin on the starboard side was used by naval surveying officers as a chart room and installed with a complete set of charts of the world, instruments such as theodolites, books, sailing directions, drawing materials and stationery.

In the central part of the main deck, storage space was found for additional scientific equipment and two smaller cabins were built abreast of the main mast. On the port side was a photographic laboratory and on the starboard side a chemical laboratory. The area between the cabins was taken over by equipment that would not fit into the workrooms, including a hydraulic press for testing thermometers and other instruments.

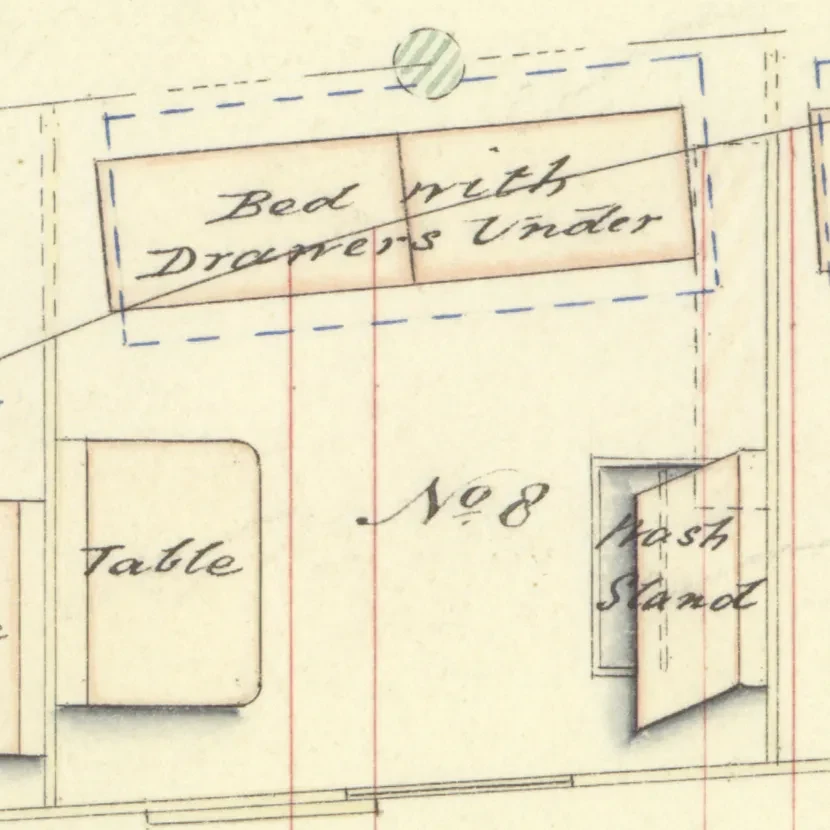

The lower deck, by contrast, remained much the same as on a standard warship.

Living quarters carefully regulated social interactions depending on rank and position. Lower-ranking members of the crew slept in hammocks forward of the main mast, while the naval and scientific staff occupied cabins with small beds located aft.

With no intention of engaging in hostilities, the positions of ship’s gunner, marine officer and chaplain remained unfilled. Furthermore, no midshipmen or subordinate officers accompanied the ship on its exploring voyage. Their designated mess was therefore demolished, making way for five cabins for the civilian staff.

The wardroom, where commissioned officers ate together, was significantly enlarged to accommodate the scientists and provided a space where they could meet informally with officers. Tizard remarked that the staff met ‘to compare notes with the others in the smoking circle daily after dinner, a function always well attended, and where the events and work of the day were freely and amicably discussed’.

This article is an edited extract from The Challenger Expedition: Exploring the Ocean's Depths by Dr Erika Jones, Curator of Navigation at Royal Museums Greenwich.

The book, published to mark the 150th anniversary of the expedition's launch, reveals the often hidden efforts and collaborations at the heart of HMS Challenger's landmark endeavour, the legacy of which shaped the development of ocean science for years to come.