How did you first get into science? Were you inspired by someone?

I always wanted to be a scientist ever since I was a kid. I grew up around the ocean—sailing, snorkeling, swimming—and I wanted a job that involved studying the sea. It seemed like science was the perfect path to make that happen. When I was younger, I was inspired by Sylvia Earl, and later Jane Lubchenco.

Was there a moment where you knew you were going to be a marine biologist?

I wanted to be a marine biologist since I was a kid—this stemmed from a deep love for and connection with the ocean from a young age. I can’t remember any part of my life without the sea. The idea of becoming a science communicator was planted later while studying marine biology at Brown University. During my senior year, I took a science communication course from Heather Leslie and my eyes were opened to the idea that communication is an essential part of science, not separate from it.

Communication is an essential part of science. It is not separate or optional.

Dr. Jennifer Adler

How did you get started in underwater photography?

I first photographed underwater while studying abroad in the Turks and Caicos with the School for Field Studies during my junior year of college. But my photos were absolutely terrible—I didn’t start photographing seriously until I was working as a scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey and then working on my PhD at the University of Florida around 2013. It was Florida’s incredible freshwater springs that inspired me to pick up a camera and document beneath the surface in these ecosystems.

As I photographed underwater, I realized how much these ecosystems were changing and started documenting these changes as well as diving deeper into the limestone caves of the aquifer, a place few people will ever see. The aquifer is the source of drinking water for more than 92% of Floridians and I found that few people understood what an aquifer is and how they’re connected to it, so I started using my photos to help connect people in Florida to the water beneath their feet, as well as the science happening beneath the surface.

Is there any advice you would like to share with women looking to get into STEM careers?

Read everything you can find. Spend time in the ecosystem you want to study. Look, observe, take notes. Think of what types of questions you’d like to answer in your research and talk to other scientists. Don’t be afraid to reach out to them. Email the authors of peer-reviewed papers that you find interesting. I got my first job at the U.S. Geological Survey by emailing a woman whose papers I admired and asking if she had any openings in her research group. She didn’t, but she sent my resume around at the office and someone else at USGS hired me.

Is there a female scientist that you particularly look up to?

There are so many! I’ve always looked up to my undergraduate advisor Heather Leslie as well as Jane Lubchenco, who was actually Heather’s PhD advisor. Heather was the one who introduced me to the field of science communication—in a senior seminar at Brown University she assigned Jane’s 1997 presidential address to AAAS, which acknowledged communication as an essential part of science. Both of these women helped me understand how I could blend my training in science with photography and writing in an impactful way.

I also really admire Jess Cramp, a shark researcher who works in the Cook Islands and is a fellow National Geographic Explorer and AAAS Ambassador. She founded Sharks Pacific and is inspiring in not only the impactful work she does that informs policy and conservation, but also in the way she communicates about being a woman in STEM and how she uplifts other women in science.

How important is it for women to see themselves represented in STEM fields?

Although similar numbers of males and females now earn scientific doctoral degrees in the United States, men dominate news stories, keynotes, invited panels, and upper-level faculty positions and the Geena Davis Institute found that only 37% of STEM characters are female. Seeing women in STEM roles is crucial to the next generation of girls picturing themselves in these fields too. It is also crucial for there to be broader representation in STEM fields with regards to race, ethnicity, nationality, etc. for the same reason.

In 2018, I documented an incredible group of female scientists planting staghorn coral in the Dry Tortugas. They outplanted 1220 corals during long, beautiful days underwater. Their drive and passion were inspiring—they can give us all hope for the future of coral reefs.

Also in 2018, I documented a few incredible scientists studying cryptobenthic reef fishes in French Polynesia, including marine ecologist Dr. Jordan Casey. She and her colleagues were visiting the Tetiaroa Society Ecostation to study small 'cryptobenthic' fishes. They targeted specific species with spear guns in order to dissect them and analyze stomach contents. This helps them understand how abundant, yet understudied, smaller fish fit into the complex marine food web.

Coral reefs support more species per square meter than any other ecosystem on Earth. Reefs also protect shorelines from storms and provide food and livelihoods for billions of people. Losing coral reefs means not only losing biodiversity but food, livelihoods, and protection from storms.

Dr. Jennifer Adler

What has been your most challenging dive?

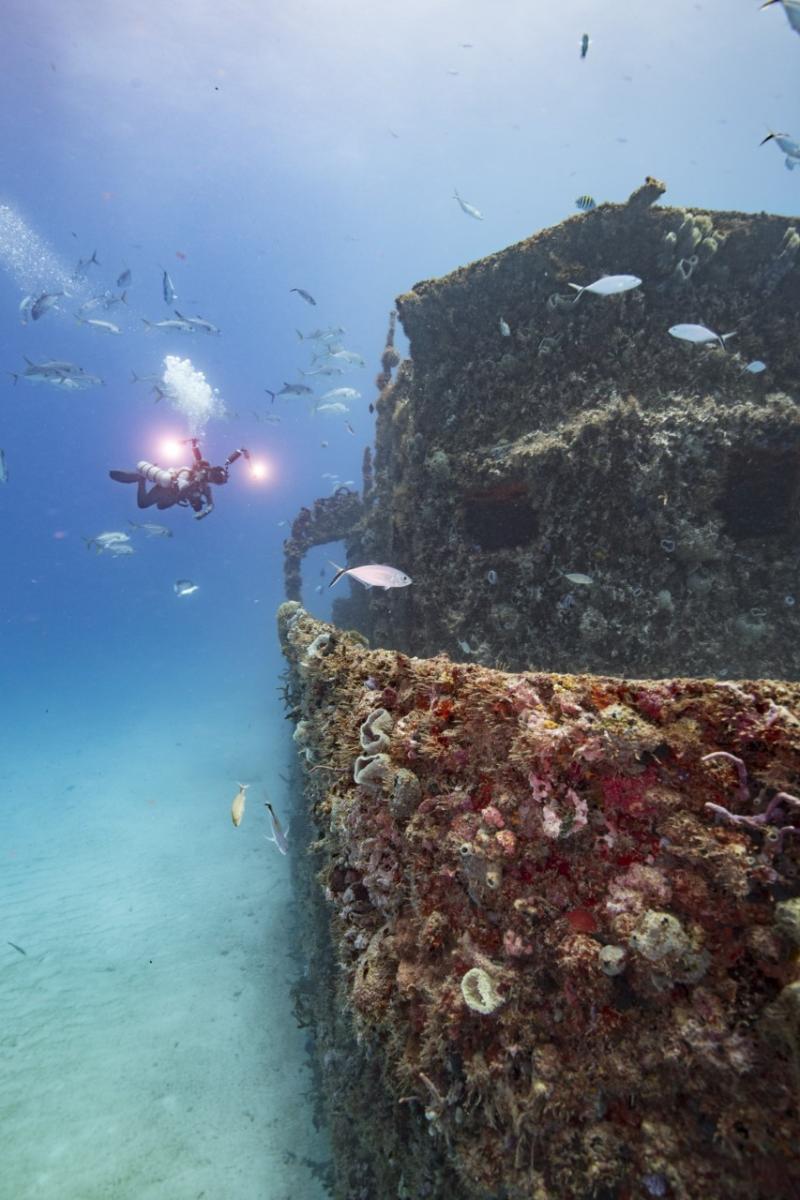

One of my most challenging dives was off Puerto Morelos, Mexico on a ship sunk as artificial reef. We splashed over the side of the boat into big waves, gripping the line so the ripping current didn’t sweep us away. We clipped on our tanks, one on each side, while being tossed in the waves and finally catching our cameras over the side of the boat while being jolted around by rough seas.

I breathe deep and exhale, descending slowly, with lights clipped to my harness, camera clutched in one hand, and mooring line in the other as Katy Fraser and I are blown sideways like flags waving in the wind. We both wonder if it’s worth it. Our captain Miguel and others have told us it’s a point of local pride and when we told them we’re documenting coral reefs, they said we shouldn’t miss it.

I can now tell you with certainty that it most absolutely was worth it. The corals covering the ship were vibrant and the surrounding waters full of fish in every shape and size. A massive cloud of schooling amberjacks swirled downstream of the ship and a pod of eagle rays soared overhead. It was perhaps the most challenging but also most rewarding dive I have done in years.

How have you witnessed the effects of climate change in your work?

I have witnessed the effects of climate change in countless ways while documenting science and conservation around the world. Warming waters, coral bleaching, dying seagrass, algae outbreaks, sea level rise, increasing coral diseases, changes in Florida’s freshwater springs. Besides climate change, I also witness countless other anthropogenic impacts such as dredging, overfishing, trash, pollution, coastal development, and so much more.

Photography can help communicate science in ways that words and numbers cannot—with emotion.

Dr. Jennifer Adler

Discover more

This article was originally published to coincide with Exposure: Lives at Sea, a photography exhibition at the National Maritime Museum.

Six seafarers and researchers shared images of their lives at sea, taken in the course of their work in some of the planet’s most challenging environments.