12 August 1809. In the French fortress of Sarre Libre, a British prisoner-of-war prepares to escape.

His plan has been months in the making. If he fails, execution awaits.

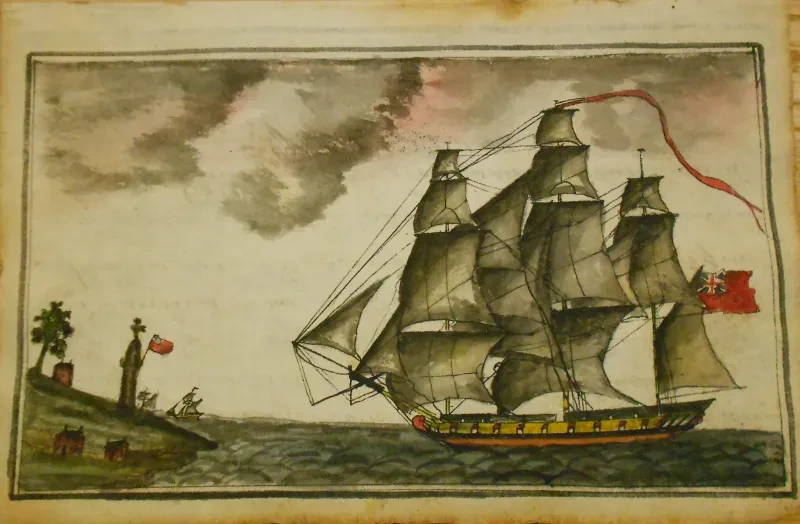

The 19-year-old seafarer escapes and flees across Europe, disguised as an officer in the French customs service. He travels through Germany and the Netherlands to reach Rotterdam. He then finds his way aboard a warship bound for Britain and is reunited with his family in Lincolnshire.

More than 200 years after this daring escape, the same uniform the sailor used as a disguise is on display at the National Maritime Museum.

This is the extraordinary tale of Charles Hare: the greatest prisoner of war escape you’ve never heard of.

Who was Charles Hare?

Born on 28 September 1789, Charles Hare began his career in the Royal Navy aged 11. It was not unusual for boys to go to sea during this period, as it meant they could complete their training before the age of 20 – the minimum age required to become a naval officer.

However, in 1801 – the same year Charles joined the Navy – his father died. As the eldest son, Charles became responsible for supporting his mother and younger siblings.

Two years later, with Britain at war with Napoleonic France, further disaster struck. Hare’s ship La Minerve was captured off the coast of France.

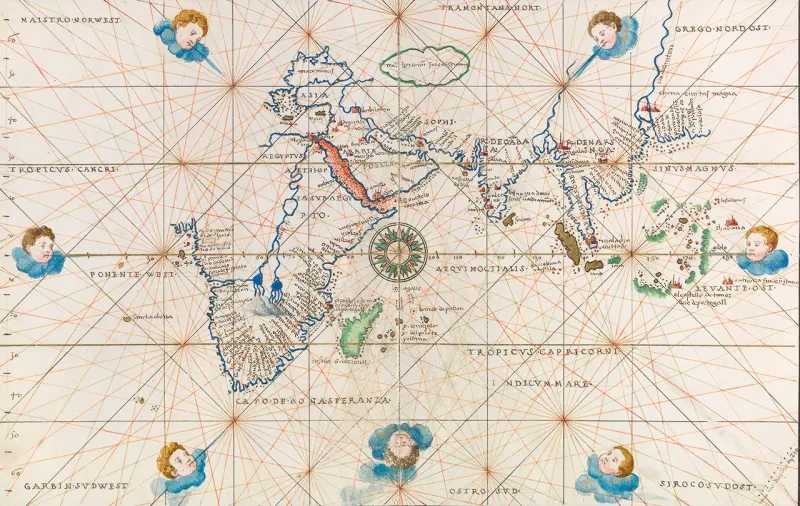

The officers and crew, including the now 13-year-old Hare, were marched hundreds of miles overland from Cherbourg to Verdun, a walled city that served as a prisoner of war depot. Hare remained at Verdun until late 1806 and was then transferred to Sarre Libre (present-day Saarlouis in Germany), where he spent a further two-and-half years in captivity.

“At this point, Hare was 19 years old, had spent most of his adolescence in prison, and hadn’t seen his family in over six years,” says Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich. “He might have remained imprisoned for many more years, had he not staged an audacious escape.”

A daring escape

“In earlier conflicts, opposing sides regularly used to swap captured sailors and soldiers, so there were very few escapes,” Gazzard explains. “However, Napoleon refused to authorise any prisoner exchanges, so captives were locked up indefinitely. Young officers didn’t want to spend crucial years of their lives and careers languishing in French prisons, which led to a rise in escapes.”

To aid his getaway, Hare made friends with a French customs officer, who hired a carriage to take him away from the prison and supplied him with false documents. He also gave Hare a French customs uniform – an ingenious disguise for a hostile country.

“French Imperial Customs officers were deployed widely across Napoleon’s Empire as part of an economic strategy to enforce an embargo on British trade,” Gazzard says. "Hare could disguise himself as a customs officer travelling across Europe on official business.”

However, it was a dangerous move. “Impersonating a French officer was regarded as espionage and was punishable by immediate execution,” she says. “There’s a real, palpable sense of fear when he writes about his own escape. He knows that if he makes even one mistake, it could result in his death.”

Hare put his escape plan into action on 12 August 1809. Once safely on board the carriage, Hare tossed his prison clothes into a cornfield and donned his disguise. The first stage of the escape had been a success.

On the run

Hare embarked on an adrenaline-fuelled dash across Europe: boat-hopping along the Rhine to Rotterdam and sneaking aboard a carriage to the Dutch coast. An account of his experiences, written retrospectively, highlights the numerous dangers he faced.

It’s a tale filled with drama and suspense. On one occasion, the disguised Hare is summoned to appear before the Commissary of Police at Cologne, who questioned all travellers passing through the town. “An interrogation from a man possessing powers of such investigation, for the first time nearly caused me to lose that presence of mind which fortunately had not yet forsaken me,” Hare recounts.

For Gazzard, some of the story’s most compelling moments are Hare’s interactions with the people he encounters. One incident sees Hare hitching a ride on a wedding barge, where he is “forced to swallow” several glasses of brandy and urged to “join chorus in French songs of gaiety.”

He also writes about the dog he adopted in prison and who accompanied him throughout his escape. At various points, Hare used the English terrier as a distraction to avoid awkward questions. He was dismayed when he lost his pet in Rotterdam. Panic-stricken, he raced to his lodgings where he found the dog shivering outside, having swum across the canals to get back to his owner.

“Hare’s account has a range of emotional beats,” Gazzard explains. “There are moments where he really communicates the danger and nervous energy, balanced by moments of levity, where his sense of humour comes through.”

The journey home

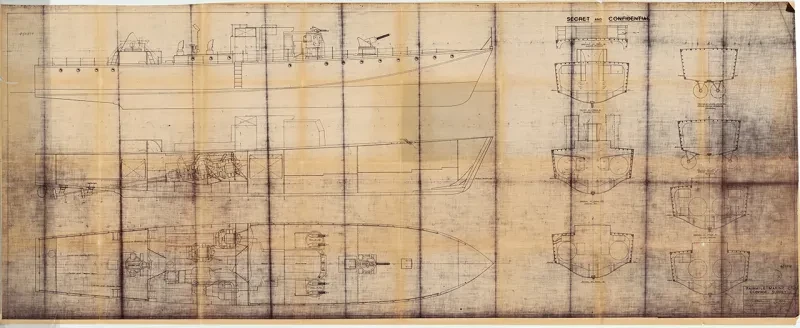

After nearly two weeks on the run, Hare enlisted the help of fishermen in Rotterdam, who rowed him out to the Royal Oak – one of several British warships blockading the harbour. He was eventually granted passage, a moment which, Gazzard explains, links to one of her favourite research discoveries.

For years, Gazzard has been looking into the wider context surrounding Charles Hare’s story; charting Hare’s escape route, studying the role and evolution of the French customs service, and delving into the experiences of prisoners of war.

At the National Archives she was thrilled to find the Royal Oak’s original muster book – a register of everyone on board the ship. Scanning through the list of entries she found the name ‘Charles Hare’, with a reference to his having escaped from prison at Sarre Libre.

“This tiny detail in the record tells us that his story is genuine,” Gazzard explains. “It is the moment that signals that he’s arrived and that he’s safe.”

In late August 1809, having walked 30 miles from Grimsby to his home in Fillingham, Lincolnshire, Hare was reunited with his family.

Life after prison

Hare’s ordeal did not deter his naval ambitions. Less than two months after returning home Hare was back at sea and promoted to lieutenant. “He was clearly ambitious and wanted to get on with his career, but he was also conscious of the need to support his family,” Gazzard says.

Hare served in North America, where he met and married Mary Stewart McGeorge in 1813. Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 Hare struggled to find postings as a naval officer, and instead found work as a merchant captain. He died in 1859, at the age of 70.

Throughout his life Hare remained proud of his daring prison break. In 1832 he wrote out the story for his seven-year-old son George.

“Hare’s family treasured his story, passing it down the generations and caring for the uniform he used as his disguise,” Gazzard says. “Now the uniform and written account have been acquired by Royal Museums Greenwich. We’re thrilled to take over the baton and continue preserving and telling his story for future generations.”

Find more stories you might like

This project was made possible by the generosity of the Anthony and Elizabeth Mellows Charitable Settlement, the Aurelius Trust, the Idlewild Trust, the Leslie Mary Carter Charitable Trust and the Radcliffe Trust.