Female sailors who ran away to sea aren’t hard to find in the 19th century.

Stories of people raised as women who lived and sailed as men became popular subjects for ballad writers and newspaper editors, and still exert a powerful draw today – but is there another way to interpret the accounts they left behind?

Independent researcher Ema Sala has been investigating the ballads, newspaper reports and biographies of these ‘female sailors’ as part of their work with the Queer History Club, a group of LGBTQ+ researchers and creatives who meet monthly at the National Maritime Museum.

Their findings suggests that, for some individuals, this transition into a different identity was more than mere disguise.

What was the popular view of female sailors in the 19th century?

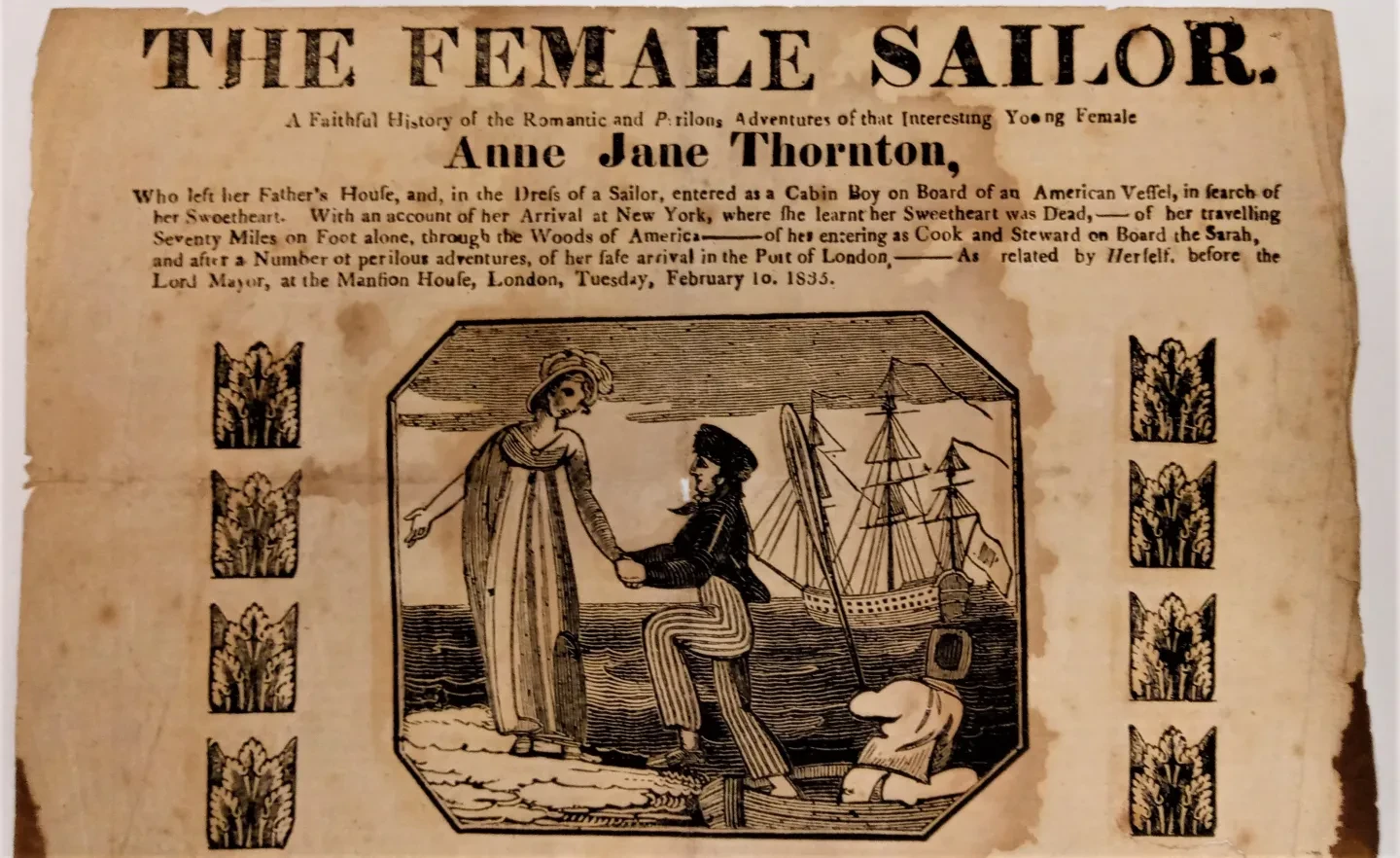

People thought that female sailors were ‘cute’ in a way. Early newspaper articles, ballads and biographies gave rise to this romantic idea that female sailors were typically girls in love with a guy who went to sea out of love.

The stereotype was that they were very good sailors – but also very delicate. When they were found out, they returned to their normal lives and went back to living as women.

This idea persists in contemporary research into female sailors, which draws on 19th century depictions whilst also introducing new ideas – for instance that they went to sea in search of economic opportunities.

What made you want to question that interpretation?

I think that narrative is undeniably attractive, but as a nonbinary person it never quite felt right. It seemed that, for some people, there could be more to this embodiment of masculinity.

These individuals had desires and motivations and joys that remain unexplored. There is this idea of a woman being ‘freed’ from a male-dominated world – but what does it mean to be free? Was it in fact more freeing for these people to embody a gender that they felt comfortable in?

At the same time, the idea that it was easier for a woman to live as a male sailor seems a bit facile. Being a sailor was a terrible, terrible job! And it wasn’t just sailors: during my research I found people who chose to remain living as men even after they were discovered, working in factories and other tough working environments.

So I had this emotional response; a feeling that there was more to this story than meets the eye. But we’re scholars, we have to be rigorous: we need to test it.

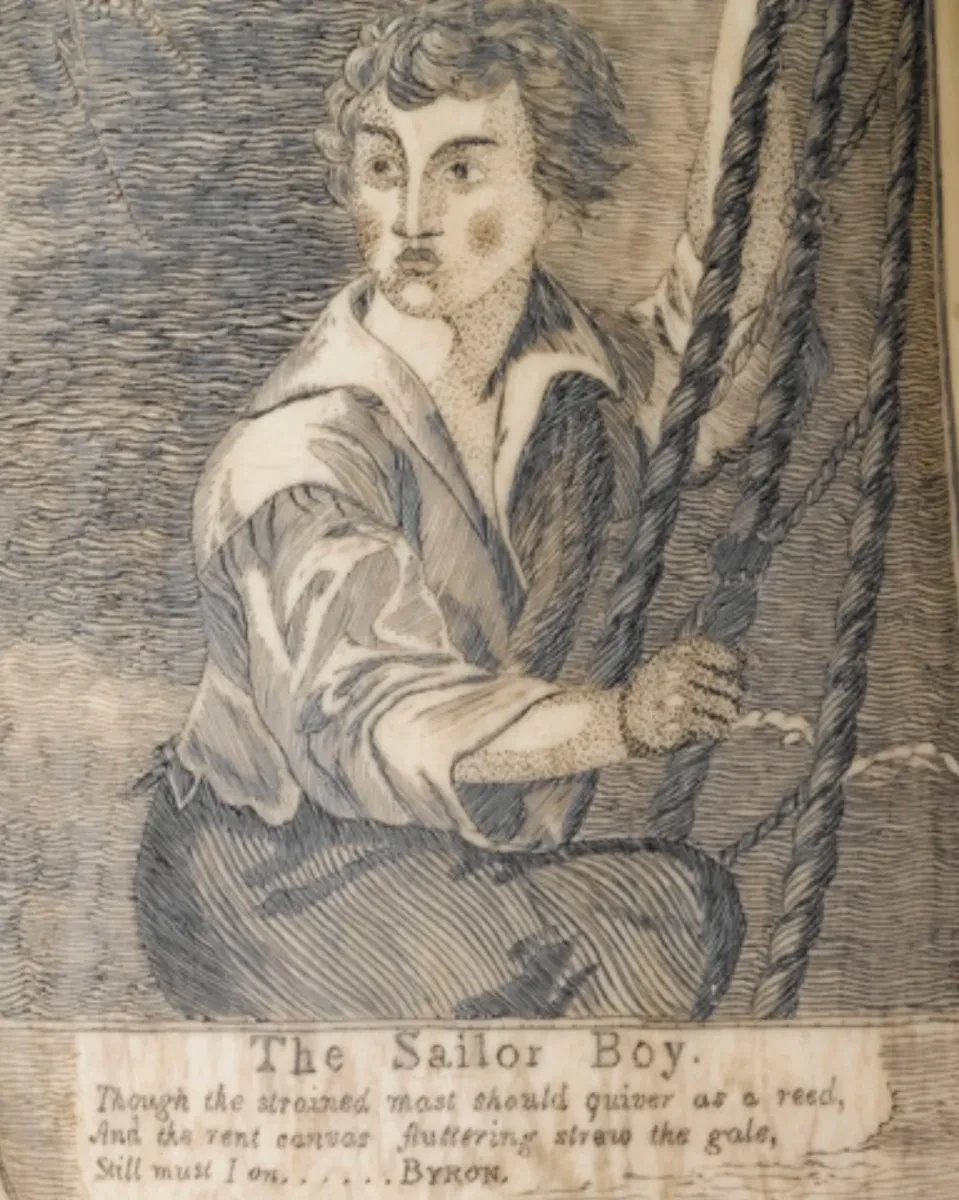

Detail from an engraved whale tooth, showing a sailor climbing a ship's rigging in a storm. The inscription is titled 'The Sailor Boy' and includes a quote from Lord Byron's narrative poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage: 'Though the strained mast should quiver as a reed, And the rent canvas fluttering strew the gale, Still must I on...'

Where did your research take you?

These characters are present everywhere: in the press, in ballads, in stories that are written about them. Many of them are real people: people who were ‘outed’ if you like.

I began by looking at female sailor ballads, and a collection at the Caird Library of documents and notes taken by folklorist and historian Roy Palmer.

But then something caught my eye: a newspaper clipping about a person – a ‘female sailor’ – who was found out while in Palermo in Italy. Palermo is my hometown, so immediately I was curious. It felt like we had chosen each other in a way: finding this person in the archives, who feels so personal to you, makes you want to learn more.

What did you find out about them?

The sailor I am investigating is so interesting because he was 'outed' not once but twice.

The first time he is found out is in 1864 while serving on a ship in Palermo. He is taken to the British Consulate, and William (as he was then known) asks if he can continue to work as a sailor in order to pay his way back. They agree.

Often when a female sailor is discovered it becomes a big news event, but William’s story doesn’t reach the papers until months later. In the meantime he has been living as a man in a lead works in Newcastle. The reports describe how everyone at the factory liked him, even after it was discovered he was assigned female at birth.

What about the second time they’re discovered?

After this encounter I thought I’d lost him. Then, while trawling the British newspaper archives, I found him again almost by accident in an account from 1868. They had misspelt his female name, which was why I’d missed him before. I almost shouted with excitement.

In 1868 he is called Thomas – his previous discovery as William had become such a big story that he had to change his name in order to continue being a sailor. To me this speaks to another thing: this person really, really wanted to be a man. It wasn’t a disguise that he was adopting.

Thomas finds his way aboard another boat, but in Bombay they find him out again, and arrange for a medical expert to examine him. I can only imagine how abusive and traumatic that must have been, but it does emphasise how seriously he was taken when he declared that he was a man.

The language the doctor uses is striking: the report says that Thomas ‘is of the female sex’. To me that phrasing feels quite modern, almost an acknowledgment that they could not call him a ‘girl’. This was a person who bridged genders.

You refer to William as he/him. How do you approach the challenge of talking about gender identities of people in the past?

In my research I use the term ‘transmasculine people’, but my definition of trans people is about what they’re doing rather than an identity: a movement from one gender presentation to another. Sometimes they move back, sometimes they remain in between.

I tend to use the pronouns they/them and the term ‘people assigned female at birth’ when referring to individuals who lived as female sailors. Of course, I cannot know what their self-perception was, so for me this is a way of acknowledging that I don’t know, and recognising that they themselves used both masculine and feminine pronouns throughout their lives.

My one exception is William. I think the documents show that he very much wanted to live as a man, and I wanted to respect that.

Was there anything you found in your research that made you uncomfortable?

When I read that they had called in a doctor to examine William, that was the point I really felt for him.

Before that, even when he had been found out and was in trouble, it almost felt swashbuckling. But his medical examination hammered home the point that this was a traumatic experience for him. I suppose it also speaks to the fact that, even today, so many trans and nonbinary people can have distressing encounters with medical figures.

Does being part of a group of LGBTQ+ history researchers help you in those situations?

Everyone is so supportive. When I brought that particular story to light, people immediately understood: yes, this was a difficult history to tell, but it was also a new discovery, something that added to our picture of William’s life.

The main thing I’ve learned from the Club is the attitude that you can bring to research. I spent so much of my time in academia trying to remove myself from the sources emotionally, but this is the complete opposite of that.

You feel completely enmeshed in these stories, and that gives you a newfound respect for the people you're researching. The records and the establishment have not always been kind to them, but these are real people, these are your people. You have to take care of them.

Ema Sala is an independent researcher and writer. You can find them on Instagram @femalesailors