Between the 1400s and 1800s, 12-15 million men, women and children were forcibly transported from Africa to the Americas.

The National Maritime Museum's Caird Library includes documents, manuscripts, books, newspapers, pamphlets and photographs that together help us understand the history and legacies of transatlantic slavery.

"These documents expose the nature – the genuine depravity – of the trade in human lives across the Atlantic," says historian S.I. Martin, who has worked extensively with the National Maritime Museum's collections.

Content warning: some of these documents contain racist or offensive terms.

This is at once a human story, but it's revealed also as a story of business. The two collide in the most horrible and prosaic manner imaginable

S.I. Martin

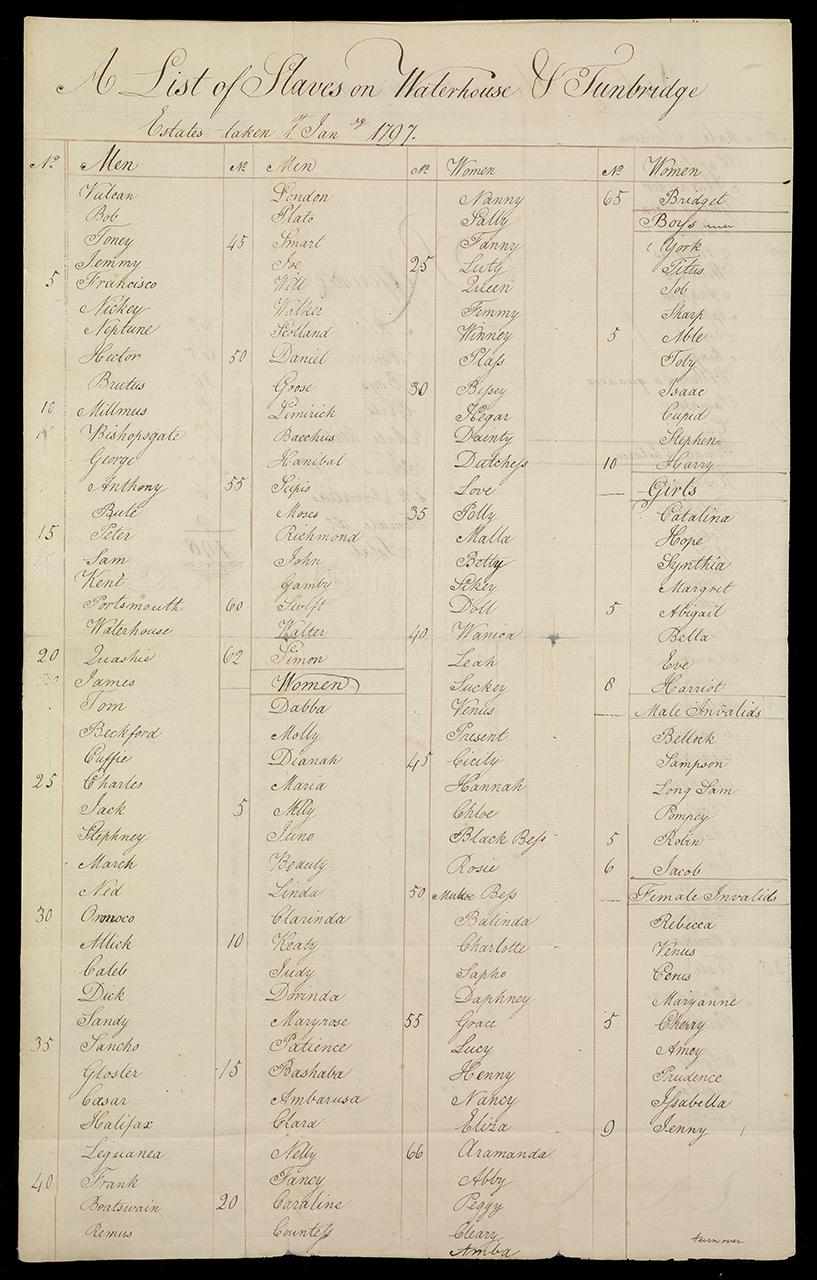

Plantation records: tracing the names and histories of enslaved people

For S.I. Martin, the plantation records held at the Caird Library's Michael Graham Stewart Collection provide a gruesome but vital connection to the lives of enslaved people in the 18th century.

"This is a typical piece of tabulated information from the year 1796. It's a list of enslaved people on the Waterhouse & Tunbridge Plantation in Jamaica," he explains.

"It's a business document – but the business is people."

Click the photograph to open the online collection record. Look at the names of the people listed: what do you notice?

"The very first name in this list is the name Vulcan," Martin points out. "You also have the name Bob. You have Neptune, Brutus, Hector – a whole host of these Greco-Roman names were given to African people. These are people whose names have been, largely speaking, removed."

Some of the men and women listed appear to have been 'given' names related to places: 'Kent', 'Portsmouth', even 'Waterhouse', the name of the plantation itself.

Others appear African in origin, although whether these people have managed to retain their actual names is unclear.

"This is part of a process by which the enslaved people are being separated from their origins," says Martin. "It reminds us that this is at once a human story – we are talking about human lives here – but in this form it's revealed also as a story of business. The two collide in the most horrible and prosaic manner imaginable."

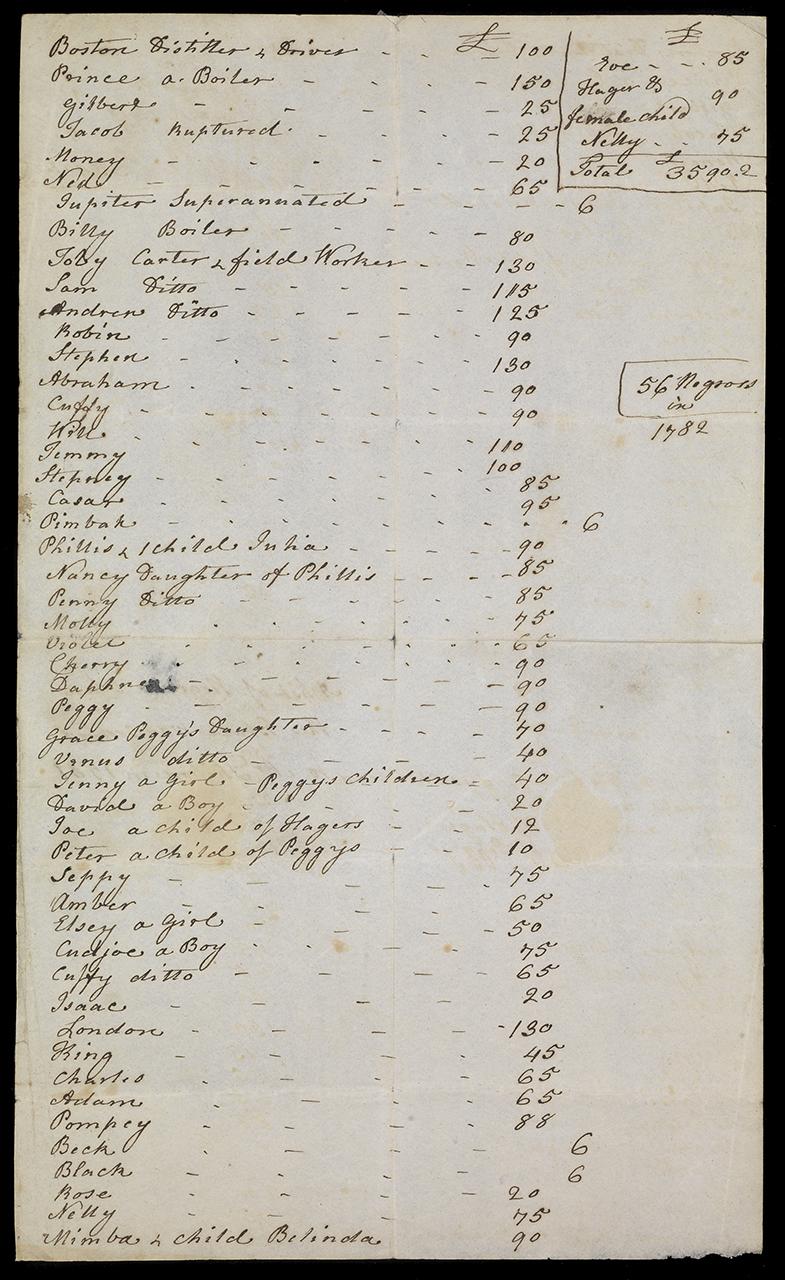

Another document from the 1780s records the names and occupations of enslaved people on an estate in Antigua.

"What is immediately affecting to me is that, like most people of African Caribbean origin, my family history is completely unreliable before the 1860s or 1850s," Martin says. "Any of these people could have been an ancestor of mine."

The record includes a value in pounds for individuals on the estate, which varies depending on the age, profession or gender of the person.

"Coming in at a value of £100 you have someone by the given name of Boston. Boston is a distiller and a driver, and is one of the more expensive lives on this sheet – because of course a distiller is a specialised occupation," he says.

"You see how the prices vary and how the lives are valued. You've got Jacob, who is apparently only worth £25 because he is, as they say, 'ruptured'."

"This is one of the ugliest documents I've ever seen," Martin concludes, "but it points to the importance of accessing material like this."

The Fort at Commenda: uncovering the architecture of slavery

"What we're looking at here is a plan of the Royal African Company's fort at Commenda in West Africa, in the year 1749," Martin says.

"This is a plan of one of a set of fortifications which was designed to consolidate and extend British power over various parts of West Africa, through which human lives were being increasingly funnelled. Remember that this is the year 1749; we're heading to the point around the 1780s where Britain is the largest trader in human lives."

The plan illustrates the various elements and fortifications of the building, designed, as Martin says, "for getting people out – as well as occasionally goods and trading items in."

"As ever it's important to remember that the trade in human lives was exactly that: it was a business. It was as banal, depraved and ugly as that, but it was a business with military and state backing."

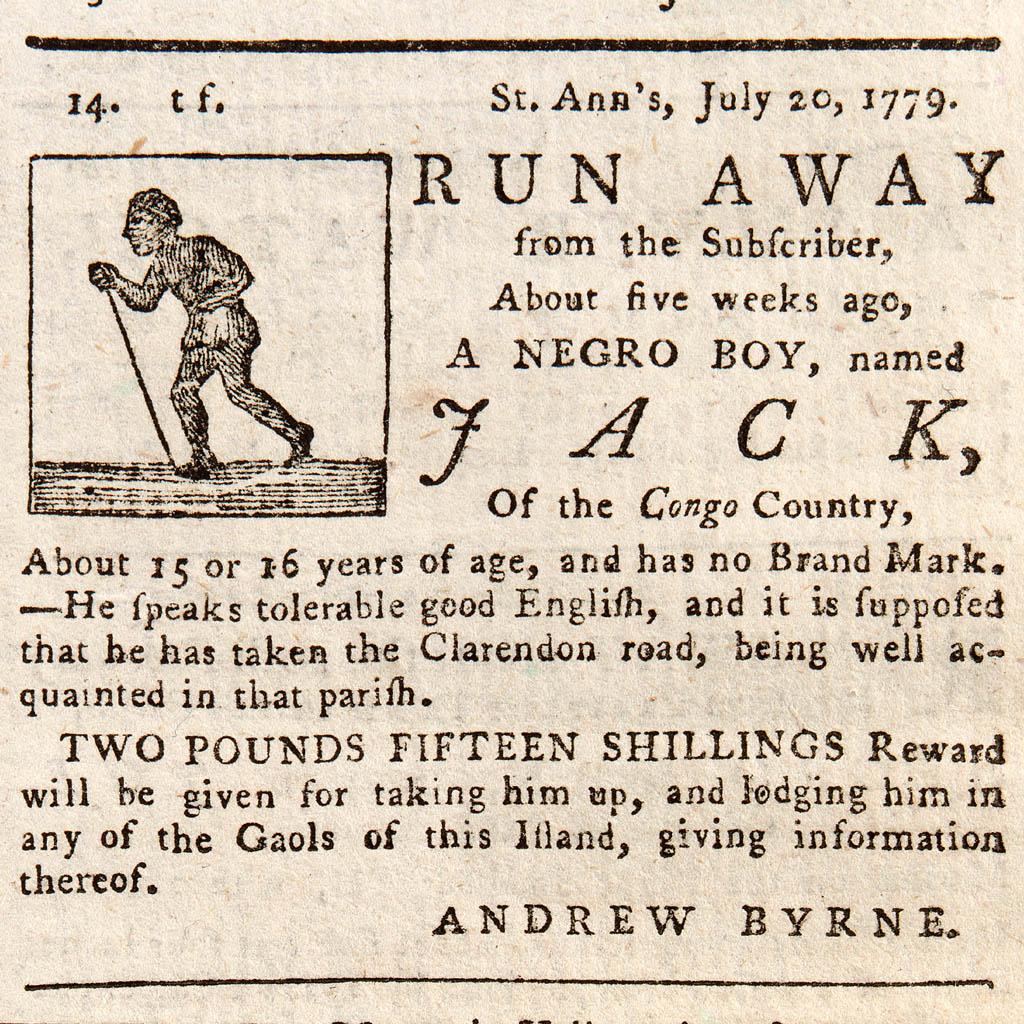

Escape and resistance: searching newspaper records for slave 'runaways'

The final document Martin examines is a copy of the Jamaica Mercury newspaper from 1779.

Along with the news reports of the day come various advertisements: for pieces of land, for language tuition, tea – and for enslaved people.

"What really catches my attention though is, you also have advertisements for runaway people," Martin says. "For enslaved people who have made what must have been the most extraordinary decision of their lives: to run away. To go for their own freedom."

This is a side of enslavement which is not really looked at very much: the fact that so many people take it upon themselves to create their own freedom

S.I. Martin

"All sorts of people summon the courage, such as this woman by the given name of 'Flora' – of course no surname.

"Flora is described as a 'North American Negro wench', and she has run away on Sunday 30 May," reads Martin.

The advert ends: 'Whoever secures said wench and delivers her to the subscriber shall receive two pounds 15 shillings reward'.

Martin explains, "This is a side of enslavement which is not really looked at very much: the fact that so many people take it upon themselves to create their own freedom; to actually liberate themselves."

Another advertisement concerns a 15 or 16-year-old runaway by the name of Jack. The text confirms that Jack ran away in July 1779; the newspaper is dated September.

"That means he's been on the run for two months," Martin points out. "We don't know ultimately what happened to Jack, but we know that there was a set of sufficiently large communities of runaways in which he could have crafted a new life for himself."