A healer, trader, preserver and transmitter of cultural knowledge: the role of the market woman has been central to Caribbean communities, but so often her importance has been overlooked.

Jacqueline Bishop wanted to explore the reasons behind this. The Jamaican-born artist and poet’s work centres on “making visible the invisible [...] speaking aloud the unspoken and voicing voicelessness.” Her art engages with a myriad of themes, from exile and memory to sexuality and desire, and spans mediums including paintings and textiles.

Bishop’s piece The Keeper of All The Secrets has been acquired by Royal Museums Greenwich and is now on display in the Queen’s House. It reworks a traditional British tea service, using collages of Caribbean market women and botanicals to explore women’s agency and the legacies of empire and enslavement.

Her artistic practice has also been shaped by the work of Stella Dadzie. An award-winning historian, Dadzie is the author of books including A Kick in the Belly: Women, Slavery and Resistance and Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain.

Here, the pair meet to discuss the inspiration behind The Keeper of All The Secrets, from the secret nature of the market woman’s work to enslaved women’s fight for bodily autonomy. Their full conversation can be viewed at the end of this article.

Content warning: This article makes reference to historic enslavement, sexual abuse and abortion.

Hidden figures: shining a light on the market woman

The market woman was originally an enslaved individual from West Africa who was central to Caribbean society, Bishop explains.

“The market woman was the face of the Caribbean," she says. “When we look at the market woman, we’re telling multiple stories at once: she carries on her head the history of the Atlantic World.”

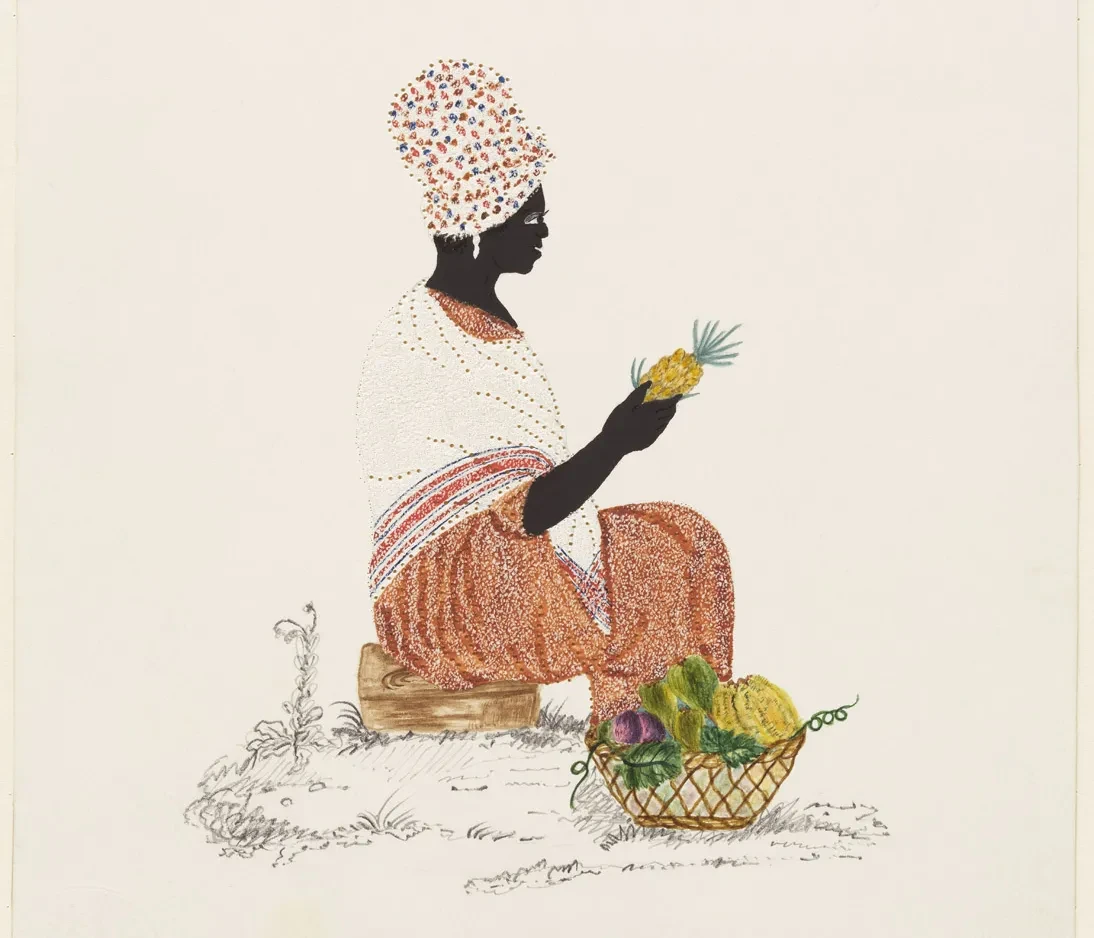

This watercolour was made in around 1820 and is thought to depict a market woman. The market woman was one of the first images to come out of plantations in Jamaica, Bishop explains. “She’s our most direct and continuing link to West Africa.”

The market woman sold a range of goods in both the town and the countryside. "She was a woman who was entrepreneurial, and who moved in different spaces,” Bishop says. The ability to move freely and unchallenged gave the market woman authority, Dadzie adds: “She comes across as a really powerful and important figure to me because she could move invisibly around the island, and that gave her all kinds of powers that most enslaved people didn’t have.”

It also meant she could be subversive. “Because she was seen everywhere, people ceased to notice her,” Dadzie says. “The capacity the market woman had to move around the island to carry produce, to interact with people, meant that she was both a carrier and a harbinger of news of subversive plots, gossip, speculation – a whole range of verbal interactions went on around her market stall.”

Granting agency

As well as selling produce, the market woman carried knowledge. She had a comprehensive understanding of the medicinal and healing properties of plants and flowers, gained from ancestral West African skills and wisdom, and interactions with Indigenous women.

In particular, she was aware of the plants and flowers that could induce abortions, and how these could empower enslaved women. “A Black woman under slavery did not own her body, did not own herself or her reproductive capabilities,” Bishop says. “The market woman was the one who knew the botanicals and the plants to give you agency and autonomy over your body.”

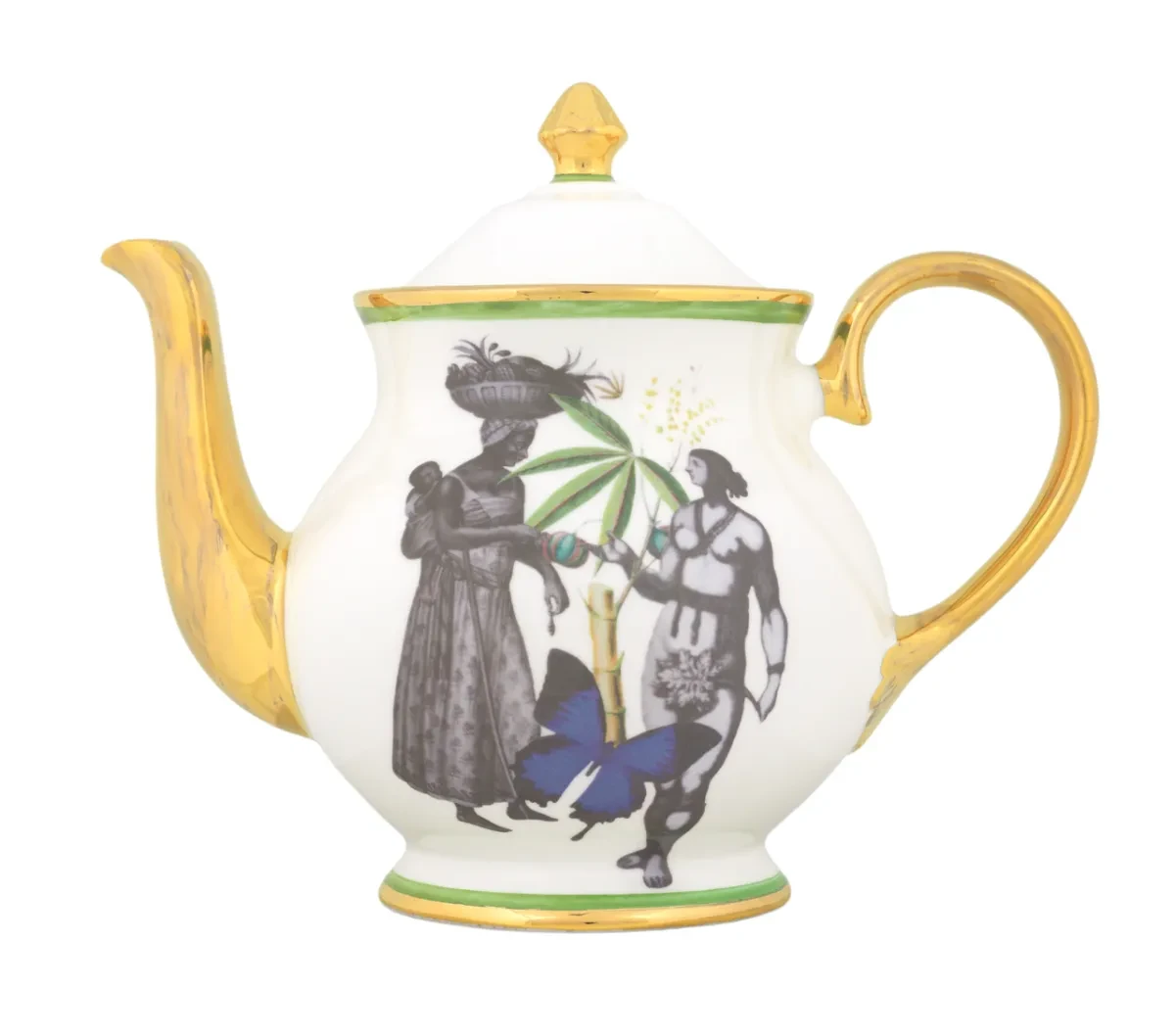

The exchange of knowledge between market women and Indigenous women forms the central image on this teapot. Cassava leaves and stems can also be seen, which were abortion-inducing substances.

The market women’s covert knowledge of the medicinal properties of plants also became a means of resistance as she enabled women to have control of their reproductive processes. Following the 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, which prohibited the trade in enslaved people in the British Empire, Black women’s bodies became the subject of debate. European plantation owners expressed concerns that the birth rate was declining rapidly, Dadzie explains, particularly in places such as Jamaica.

“When the Slave Trade ended, it became important for the population to keep breeding, and more pressure was applied to Black women’s bodies,” Bishop adds. “The ways in which Black women fought back for control of their bodies were through botanicals.”

Discover more great art

Sign up to the art newsletter for more information about Royal Museums Greenwich's art collection, and learn about upcoming exhibitions and events.

The Keeper of All The Secrets

Dispensing plants to aid abortion was an illegal practice. The market woman had to carry out her work in secret, to protect herself and the women she was helping. “The market woman had to keep and hold the secrets of the people around her,” Bishop says.

For the artist, the figure of the market woman has strong personal associations – both her grandmother and great-grandmother carried out the role in Jamaica. The idea for The Keeper of All The Secrets came when Bishop was looking through her late grandmother’s plate cabinets. “These plates had a colonial history,” Bishop explains, “and I decided: what if I started telling our history and my own history on these plates?”

Her finished work is a 13-piece 'tea service' in ceramic with digital print transfers and adorned with gold lustre. By using this form, Bishop highlights how enslavement, colonisation and empire were bound up with the trades in sugar and tea, which gave rise to luxury commodities enjoyed in Europe.

The work also reveals how tea – a symbol of British identity – was built on colonial trade networks and the labour of enslaved people. “The subterfuge that involved moving tea between China and India to make this British product is something that I want to explore more,” she says. “I wanted to create a tea service because many botanicals came in the form of teas, and you cannot think of tea without thinking of Britain, colonisation and empire.”

The use of porcelain was also significant, Bishop explains. “It is a very white medium, and I am interested in how these figures that I am putting onto porcelain move about in that white space,” she says. “The work on these porcelain plates is meant to exemplify my position as someone who is Black, who is born within the diaspora and has to navigate herself in very white spaces.”

Expanding narratives

The Keeper of All The Secrets is on display in the Queen’s House – a space that was designed by queens including Anne of Denmark and Henrietta Maria – which Bishop finds fitting. “To have the narrative of The Keeper of All The Secrets be part of a feminine narrative is deeply moving,” she says. A programme of events will unpick the themes within the work, from talks to wellbeing workshops.

For Dadzie, this acquisition is significant. “It’s essential that people come to a place like the Queen’s House and have conversations about this work, to lead them into other areas and perspectives.”

Broadening and expanding historical narratives is crucial, she says. “There’s no such thing as Black history. There’s simply that hidden history, all those hidden voices and narratives and stories and perspectives that have been airbrushed out of the picture because of who had the power to control the story.” She adds: “Bringing the story of Black women – and the role played by enslaved people – into the centre of stories surrounding Britain’s maritime glory is key.”

Watch the full conversation

Read more

Credits

Supported by Cockayne Grants for the Arts, a Donor Advised Fund, held at The Prism Charitable Trust.

The Keeper of All The Secrets display in the Queen’s House has been developed in partnership with Culture&, as part of their Time, Space and Empire programme.

Credits: The Keeper of All The Secrets © Jacqueline Bishop