For more than six years, contemporary artist Wayne Binitie has explored the ice core laboratory at British Antarctic Survey.

It is here that ice cores, extracted from Antarctica and the Arctic, are sliced, examined and analysed.

For Binitie, both the ice and the space of the laboratory itself can help us reflect on our changing planet.

"Although not a library or archive, the laboratory is a significant repository of water, words and stories, articulating the indivisibility of a polar world in extremis," Binitie writes.

One of his pieces, 'Dark Bubbles', is now on display in the National Maritime Museum's new gallery Poles Apart: Explore the World of RRS Sir David Attenborough.

Binitie tells us more about his work, and considers how art can respond to the climate crisis.

The story of 'Dark Bubbles'

My first view of Antarctica arrives as an ‘elsewhere’ from behind a lens.

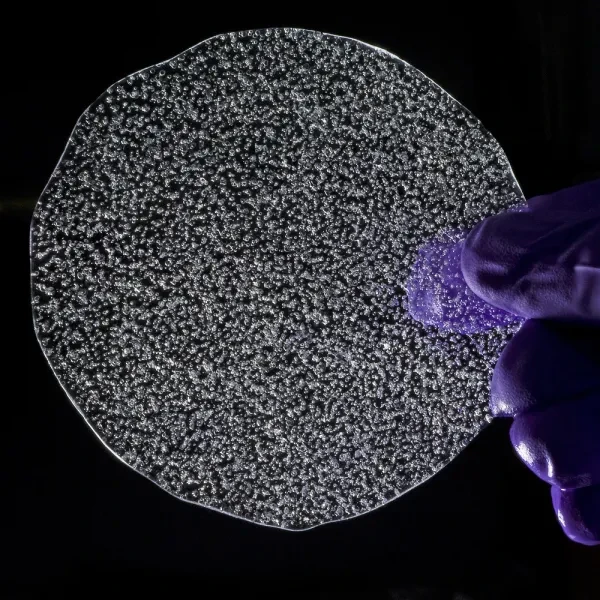

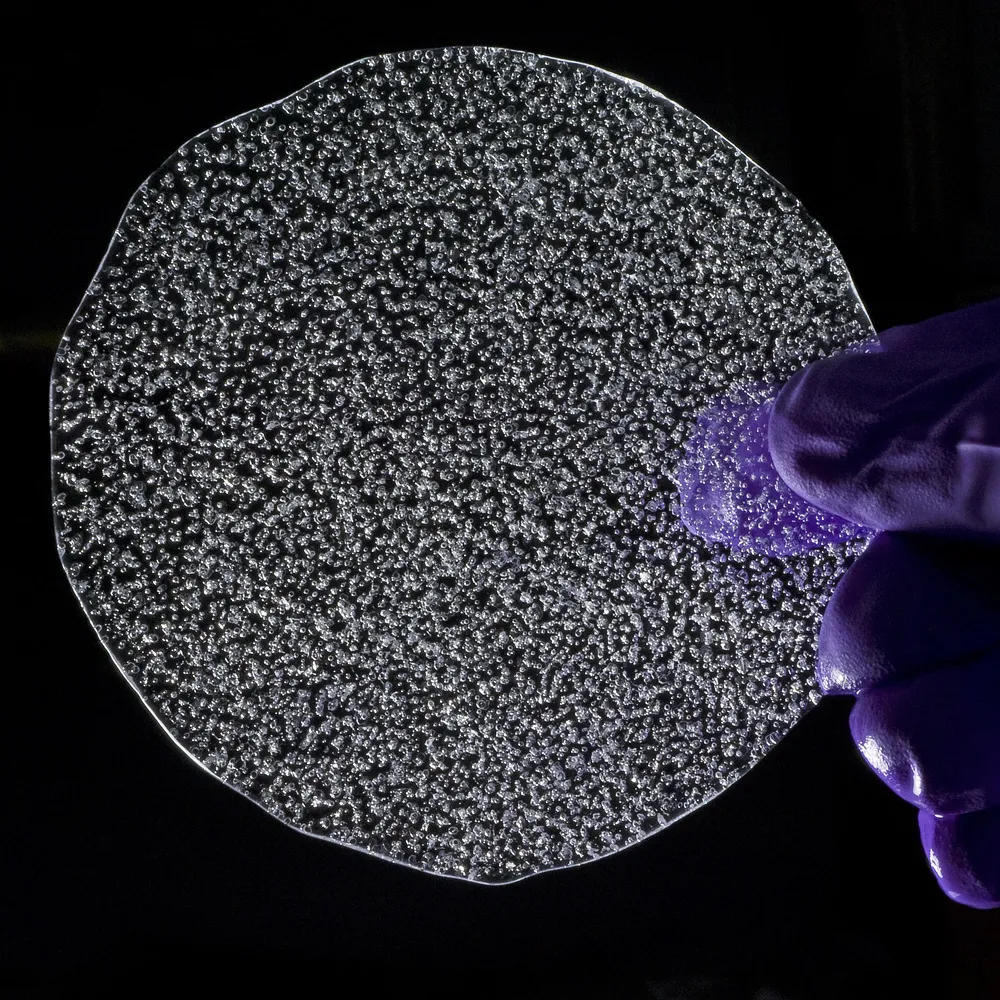

Using a high-definition camera and attached condenser radio microphone, the film captures my first documentation of Antarctic ice-core samples, held in a glass container at the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge.

The camera’s light meter and lens cannot properly calibrate the speed with which the solid samples disintegrate in liquid motion. Even after several attempts the recordings continue to shift in and out of focus, and initially appear disappointing.

However, the cracking, popping, fizzing and exploding sound recordings are instantly mesmeric. They will be later used as the basis of original sonic composition.

The 'dark bubbles' themselves are escaping atmospheric gases, mainly carbon dioxide and methane, which have been trapped inside accumulated layers of ice.

This ice was drilled by British Antarctic Survey glaciologist Robert Mulvaney from the Dyer Plateau, northern Antarctica at 70°40'16.0"S 64°52'30.0"W. The drilling took place at a sea elevation of 2,002 metres, and the team managed to drill down two kilometres below the surface. The designated ice-core samples arrived frozen solid in a small metal flask. After an hour, they had melted.

My first attempt is a filmic failure, and it will be several months before I fully understand what I have just recorded.

A world away?

Using Binitie's coordinates, we can find the exact spot where the ice-core sample was extracted.

The secrets of ice cores

The British Antarctic Survey ice core laboratory in Cambridge holds an important collection of ice cores from both the Arctic and Antarctic polar regions.

Dating back 800,000 years in geological time, ice cores contain the most accurate climatic records found anywhere on Earth, including compositional changes in both temperature and concentration of atmospheric gases. They are cylinders, drilled from an ice sheet or glacier, that scientists use to measure and predict the direct correlation between accelerating global warming, rapid melting of glaciers and rising sea levels.

They also produce popping sounds when dissolved in water. For the past six years I have been conducting audio-visual recordings at the ice core laboratory.

During my doctoral research, I created three integrated bodies of written and practical work. The work was informed by my real and imagined experience of the Arctic in southern Iceland and Rothera in northern Antarctica. I documented and interpreted how ideas of polar water, as experienced through contemporary artworks, contribute to our understanding of time, place and memory. These ideas were further refined through my central case study, Roni Horn’s Library of Water (2017).

The research examines the threat posed by the current climate crisis at the site at which its consequences are most clearly apparent – the polar waters of the Arctic north and the Antarctic south.

'To touch and be in touch with the Earth'

I am interested in how Arctic and Antarctic history is written, read and erased in the present.

In 2021 my work Polar Zero was exhibited at the Glasgow Science Centre, coinciding with the COP26 climate change conference.

Polar Zero was a UKRI-funded commission and an art, science and engineering collaboration between British Antarctic Survey, Arup and the Royal College of Art.

The centerpiece was 1765 – a cylindrical glass sculpture, encasing Antarctic air from the last possible date before the Industrial Revolution started to contaminate both atmosphere and climate. Alongside 1765 was Ice Core, a single column of ice taken from below the surface of Antarctica.

The final element, Ice Stories, was a multi-format work including words inscribed on the floor, a book, sound and film. The work consisted of anecdotes, memories and oral testimonies from national and international scientists and experts, whose lived experiences of the polar regions enable its narrative history to be written.

Together, the three artworks offered a sense of proximity to what is often a distant and remote conversation.

COP26 was hosted in the city of Glasgow, home of Scottish inventor, engineer and industrial pioneer James Watt. As such, it felt like the natural place to exhibit the work. After all, it was Watt’s improvement of the steam engine that unwittingly set in motion the environmental devastation resulting from the Industrial Revolution.

At a time of increased spatial distance, environmental fracture and sensory isolation, Polar Zero explored and revealed what it means to touch and be in touch with the Earth.

For all its industrial high tech, there seemed to be a meditative quality about the final exhibition space. I wanted visitors to arrive and depart with a greater awareness of our relationship to the glacial past, present and future. 1765 and Ice Core stood just a few metres apart in the darkened exhibition space, illuminated by LED white light, aligned in direct parallel.

I thought that if I presented an apparently empty space with two opposing forms – one permanent, one impermanent – but didn’t fully explain their correlation, just have them there, then I might be able to create an intriguing space of imagination for COP26 visitors to inhabit. And perhaps then I would be able to create an interesting vacuum, momentum and mystery.

A work 20,000 years in the making

My exhibitions to date are all informed by ideas of memory and recall, remembering and forgetting.

Ice Floor (2019) was a commissioned artwork about climate change, developed with Arup Phase 2 and British Antarctic Survey.

Leaving the brightly lit foyer of Arup’s corporate headquarters, visitors slip through grey felt curtains into a small dark room where the temperature is kept at minus six degrees Celsius. A low, circular container, with a wide rim that doubles as a seating bench, occupies the room’s centre; it is filled with freshly cut circular slices of ice sitting on a solid ice floor.

Lit from above, below and within, the container and its cargo glow futuristically in the surrounding darkness. Slowly eroding over the course of the exhibition, the ice slices are sections of a 20,000 year-old ice core, extracted from two kilometres below the surface of the Dyer Plateau in northern Antarctica.

From the outset, I stated my desire to produce an installation with a low carbon remit, where the ice, and the visitors’ tactile experience of it, was the art. Moving beyond surface intellectual debates, I wanted to explore emotionally that which lies beneath.

Ice Floor brought the transformative atmosphere of the polar regions alive through the non-human power of temperature, and the human power of touch. During the course of three months, over 2,400 visitors were able to hold a fragment of polar history in the palms of their hands. Accumulated slowly over geological time and place, this material form of 'polar memory' is always solidifying, freezing, melting or vanishing into thin air. Aiming to collapse distances of time and place, north and south, the installation sought to situate renewed critical proximity to a distant, remote and conventionally inaccessible polar world.

To mitigate temperature and humidity, only a small number of visitors were allowed into the exhibition space at any one time, creating a heightened sense of anticipation for audiences queuing outside. To moderate the solidity of the ice over the course of the exhibition, temperatures were kept to minus six degrees Celsius. Woollen blankets were offered at the entrance to keep visitors warm.

The chemical phase transition from a solid to a liquid is melting; going from a solid directly to a gas is sublimation. At minus six degrees, the ice did not melt. As a result, visitors’ breath was frozen and refrozen accumulatively into the ice. It had sublimed, becoming an integral part of the work.

Art is an encapsulation of a lot of complexity. A subject like climate change, which is so incredibly complex – you need to engage with it emotionally. That’s what I think is so powerful really: you can look at a piece of art which has been stimulated by climate change, and it sets your mind turning over, contemplating things in a different way

Jo Da Silva, Arup engineer and Global Sustainable Development Leader

Getting to heart of the matter

My work documents and explores the British Antarctic Survey ice-core laboratory as a vital, yet critically underexplored, source of polar narrative. Although not a library or archive, the laboratory is a significant repository of water, words and stories, articulating the indivisibility of a polar world in extremis.

The ice core laboratory contains polar water from both the Arctic and Antarctic. They contain vital climatic and atmospheric records used by climate scientists to model and predict the transformation of the planet. Arguing for a more profound awareness of the polar future, my research explores the solid, liquid and vapour states of water at the laboratory to rethink how polar history is written, read and erased in the present.

The noun core derives from the Old French Coeur, meaning ‘core of the fruit’ or more literally, ‘heart’. My exploration of atmospheric gases trapped inside ice-core samples is a drilling into the heart of the story – its essential part or very centre.