Who owns the Moon?

Anyone can enjoy looking at the Moon, but can anybody claim to 'own' it? Find out about the laws governing nations and people in outer space - and why 'buying' a plot of land on the Moon might not be all that it seems.

Who owns the Moon?

According to the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the exploration and use of space shall be carried out in the interests of all countries: outer space is the "province of all mankind".

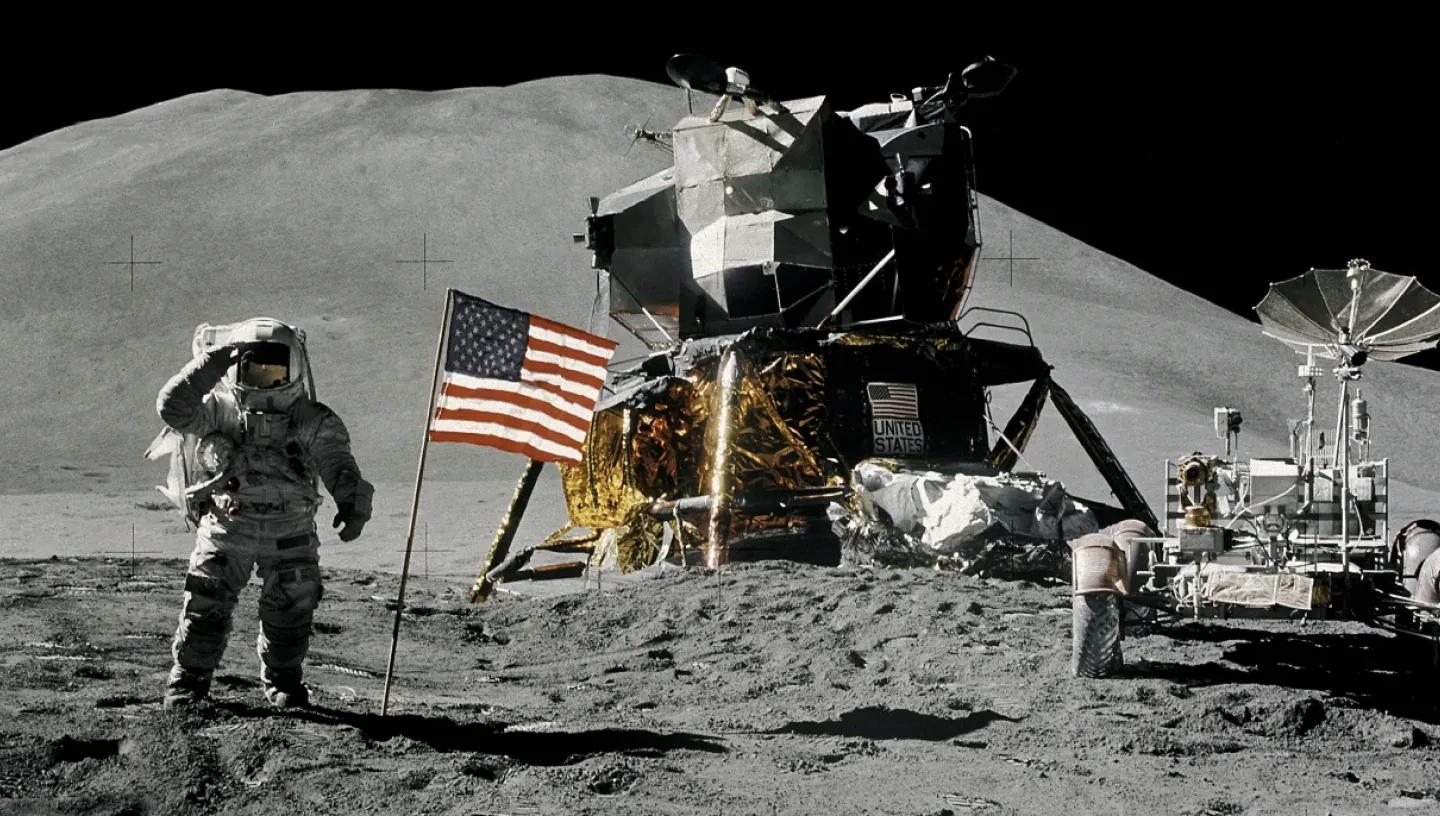

The Outer Space Treaty means therefore that - no matter whose national flags are planted on the lunar surface - no nation can 'own' the Moon.

As of 2019, 109 nations are bound by the Treaty, and another 23 have signed the agreement but have yet to be officially recognised.

What is the Outer Space Treaty?

The Outer Space Treaty is a list of guiding principles determining what nations can and cannot do in space. It also concerns planets and celestial bodies such as asteroids and the Moon.

The treaty's formal title is the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.

The Treaty was enacted during the Space Race by the USA, UK and Soviet Union on 27 January 1967, and has become the foundation for laws governing activities in space ever since.

The document is just 17 short articles in length. By comparison, the International Law of the Sea Treaty — the set of rules governing the use of the world's oceans — contains over 300 articles.

In short, the Outer Space Treaty states:

- The exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all nations and shall be the province of all humankind

- Outer space shall be free for exploration and use by all countries

- Outer space is not subject to national appropriation or ownership

- States shall not place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in outer space

- The Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used exclusively for peaceful purposes

- Astronauts are regarded as representatives of humanity by all nations, and shall be given all possible assistance in the event of accident or emergency

- States shall be responsible for national space activities, whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities

- States shall be liable for damage caused by their space objects

- States shall retain ownership and jurisdiction over any object they launch into outer space

- States shall avoid harmful contamination of space and celestial bodies.

The strange things humans have left on the Moon

But haven't people tried to buy and sell land on the Moon?

The Treaty has not stopped numerous claims of ownership from private individuals and companies over the years.

"According to the Outer Space Treaty, no country can lay claim to a celestial body. Does that mean that an individual or a company can? Some have made this claim, sometimes seriously and sometimes spuriously," writes space law expert Dr Jill Stuart in The Moon Exhibition Book.

"For a period of time it was fashionable to ‘buy a plot of land on the Moon’ as a novelty gift, with companies involved saying they had claimed the territory there as they were not subject to the Treaty's ‘national appropriation’ or ‘sovereignty’ clauses," Stuart explains.

In 1996, German citizen Martin Juergens declared that the Moon belonged to his family, claiming that it had been presented to his ancestors in 1756 by Prussian King Frederick the Great as a gift of service. Juergens petitioned the German government to take the matter to the US. Not surprisingly, no action has been taken by either government.

Private companies, meanwhile, have been 'selling' plots of land on the Moon since at least the 1950s. One of the most publicised examples is Dennis Hope's Moon real estate company, Lunar Embassy.

Believing that he had found a loophole in the Outer Space Treaty, Hope started selling plots on the Moon for $25 per acre. Since the 1980s, he claims he has sold more than 611 million acres of land on the Moon.

Hope claims that, as a private company, his enterprise is not bound by the Outer Space Treaty. However, experts in space law have argued that if nation states cannot lay claim to outer space, then by implication neither can citizens or businesses of that state.

As Dr Stuart says, "At the risk of disappointing any proud owners, claims to land would be very unlikely to be upheld under international law and in any case several companies claimed the same plots of land many times over."

The missions before the Moon landing

What other laws govern space?

Three other treaties were drafted and widely ratified following the Outer Space Treaty. These relate to astronaut rescue, liability for damage caused by objects in space, and registration of objects launched into space.

In 1979, an additional space treaty was drafted specifically to govern the exploration and use of the Moon and other celestial bodies. This Treaty was formally titled the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, also known as the Moon Agreement.

The new agreement advances the original Outer Space Treaty with further articles, such as:

- Banning any military use of moons and celestial bodies, including weapons testing and military bases

- Banning all exploration and usage of the Moon and other celestial bodies without the approval or benefit of other states

- Declaring that the Moon and its natural resources are the "common heritage of mankind", and that no state or organisation can claim to 'own' the resources available on the Moon.

However, as of 2019, only 18 nations have signed up to the Moon Treaty, with very few of them being spacefaring countries. China, the USA and Russia have not signed the agreement.

How does the law work in space?

As space is not owned, the question as to which country's authority and jurisdiction applies when a crime has been committed has no simple answer. Space, like the open ocean, is considered "res nullius", meaning it belongs to no one.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty provides the foundation for space law. In article eight of the agreement, for example, nations agree to "retain jurisdiction and control" over any object or personnel they launch into space.

However, the reality of 21st century space exploration is very different to when the Treaty was first drawn up in the 1960s, as space policy expert Dr Stuart makes clear:

Topics such as tourism, mining colonisation and celestial ownership have legal, ethical and philosophical implications that variously capture the attention of politicians, lawyers, academics and the media. However, at the core of them all is the changing profile of those who are participating in space activities. Once primarily the domain of an elite number of states, today space is accessible to a large number of countries and a diversity of non-state entities.

Dr Jill Stuart, The Moon Exhibition Book

Many nations and private companies now have the ability to send crafts and objects into space. Multi-government initiatives such as the International Space Station (ISS) or European Space Agency (ESA) complicate the legal picture still further.

On board the ISS, an intergovernmental agreement (IGA) was created in 1998 to ensure cooperation between nations, including the USA, Canada, Japan, Russia and several European countries.

According to the IGA, each state is expected to exercise criminal jurisdiction over personnel from their respective nation. For example, the US would investigate an alleged crime committed by a NASA astronaut, and Russia would investigate an alleged crime by a cosmonaut.

What was the first law broken in space?

To date, no laws are known to have been broken in space. However, in 2019, what is believed to be the first allegation of a crime committed in space occurred.

In August 2019, the New York Times reported that NASA was investigating US astronaut Anne McClain. It was claimed she had illegally accessed the financial information of her estranged wife while living aboard the International Space Station. McClain denies the claims, stating she accessed the account in order to ensure there were enough funds to support her spouse's son, who they had been raising together prior to the split.

Minor misbehaviours

While there have not been any actual crimes reported in space, there have been minor misdemeanours.

Sandwiches in space

On 23 March 1965, during the Gemini 3 mission, astronaut John Young removed from his spacesuit a corned beef sandwich which he had smuggled on board the spacecraft. Young offered the sandwich to fellow pilot Gus Grissom, who took a few bites before putting it in his pocket.

The moment was only a brief exchange captured on the mission's audio, but back on Earth it became a more serious issue, with NASA officials called to testify in front of a review in Congress. Young received an official reprimand.

NASA charged with littering

On 11 July 1979, the world's first space station, Skylab, burned up on re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. However, debris which hadn't wholly disintegrated scattered in part across a sparsely populated area of western Australia. When the Skylab investigation team visited the site to collect the debris, they were handed a $400 fine for littering.

While the fine was meant as a light-hearted joke, it did arguably have legal justification. As stated in Article 7 of the Outer Space Treaty: "States shall be liable for damage caused by their space objects."

On the 30th anniversary of Skylab's re-entry, the fine was finally paid on behalf of NASA by an American radio station.

Golfing on the Moon

The first American to travel into space also became one of the first people to smuggle an object onto the Moon.

As part of the Apollo 14 mission, Alan Shepard was the fifth, and oldest, person to walk on the Moon. At the lunar module landing site, Shepard attached a 6-iron golf club head to a rock sample tool. He took two golf balls and hit them across the lunar surface.

Shepard's golf club head is still attached to the space tool and is on display at the US Golf Association's Golf Museum.