Delve into 500 years of history, and discover how portraiture has shaped our understanding of the royal family.

Book tickets to the exhibition

Henry VII by unidentified artist, 1505

The oldest object in the exhibition, this painting was created as part of unsuccessful marriage negotiations with Margaret of Austria. It shows Henry as an astute and cunning king.

Before paintings like this, representations of English kings and queens were often standardised images, with few hints as to their true likenesses or characters. This changed during the Tudor era: for the first time, people could see what their monarch actually looked like.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

In some ways this portrait of the first Tudor monarch marks the beginning of an English tradition of portrait painting.

Kristian Martin, exhibition curator

Anne Boleyn by an unidentified artist, late 16th century

This beguiling portrait conforms to descriptions of Anne, Henry VIII’s second wife, as having a long neck and black and beautiful eyes.

No portraits remain of Anne that were painted during her lifetime, but this is the finest version of a work made around the time of her marriage to the king.

Kristian Martin

Elizabeth I (the 'Ditchley portrait') by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, about 1592

This painting was probably commissioned by Sir Henry Lee, a favourite courtier of Elizabeth I and the first person to hold the office of 'Queen’s Champion'. Like many portraits of Elizabeth, the painting is filled with symbolism – the storms behind her and the clear skies ahead, referring to her forgiving nature. She is standing on a globe of the world, with her feet on Oxfordshire - site of Lee's Ditchley home.

This portrait shows just how skilful Elizabeth I’s portraitists were in using symbolic language to convey how the queen wanted to be seen. Her portraits were designed to amaze, inspire and intimidate.

Kristian Martin

Henrietta Maria, after Sir Anthony Van Dyck, 17th century, based on a work of about 1632-35

Henrietta Maria married Charles I in 1625, shortly after he became king. Our understanding of Charles I and his court is largely defined by the portraits of Flemish artist Anthony Van Dyck, who painted several portraits of the royal family. These paintings were often given as gifts to royal supporters at home and abroad.

A master in rendering fashion, fabric and flesh, Anthony van Dyck created some of the most enduring and reproduced images of the royal family, including Queen Henrietta Maria.

Kristian Martin

Charles II, attributed to Thomas Hawker, about 1680

This imposing portrait was painted in the last decade of Charles II’s life. It depicts him as a rather jaded and tired 50-year-old king. It perhaps reflects the political situation at the time: Charles had no legitimate children, leading to worries that his Roman Catholic brother would inherit the throne.

There’s a really curious contrast here between Charles’s relaxed pose and his formal kingly attire.

Kristian Martin

George III by studio of Allan Ramsay, based on a work of 1761-62

This portrait was painted shortly after George III’s coronation. It became the definitive portrait of the king.

There was an insatiable appetite for this painting from courtiers, heads of state, corporations, ambassadors and colonial governors, which meant that Allan Ramsay’s studio was crowded with versions in various states of completion.

Kristian Martin

Queen Victoria by Sir George Hayter, 1863, based on a work of 1838

Victoria’s coronation was hailed as a new era of hope and optimism for Britain. That wave of feeling is conveyed in her portrait, with her upturned gaze and a shaft of light illuminating the scene. This official coronation portrait is also full of the traditions of royal iconography, including a sceptre, Imperial State Crown and coronation robes.

If there was a template for a royal portrait then it would surely be this.

Kristian Martin

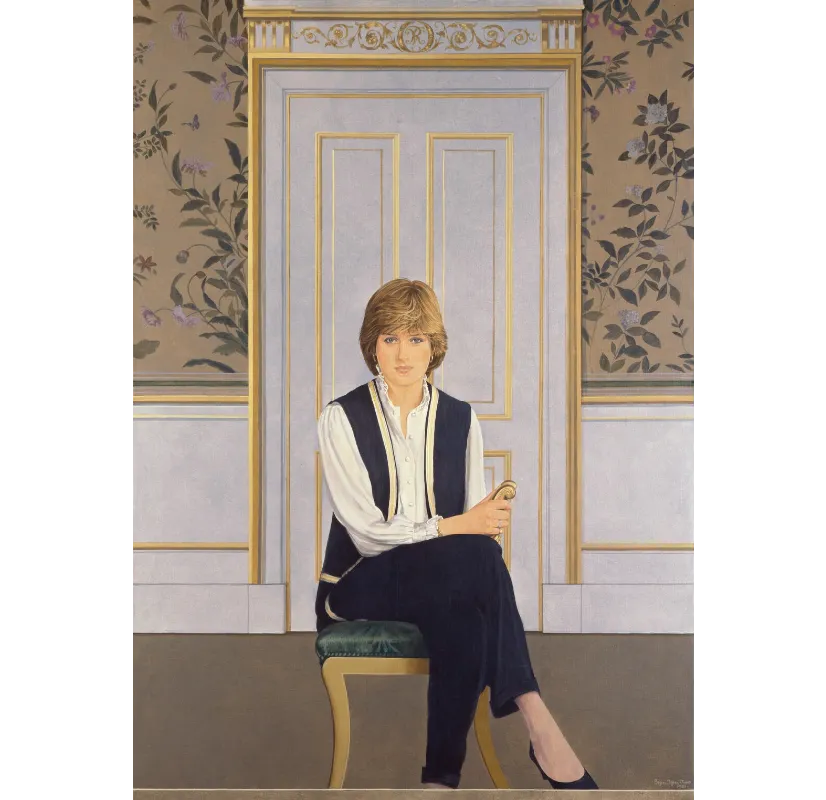

Diana, Princess of Wales by Bryan Organ, 1981

The National Portrait Gallery commissioned this work to mark the engagement of Lady Diana Spencer to the Prince of Wales. The painting, which depicts Diana in the Yellow Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace, attracted widespread interest, in particular for the unusual depiction of a female member of the royal family wearing trousers.