Two ships, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, left England in 1845 in order to search for the Northwest Passage - a vital sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

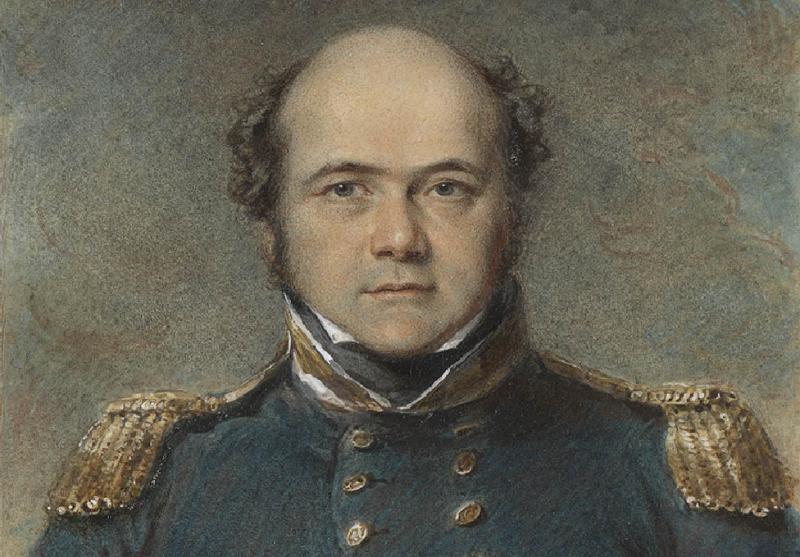

The expedition was commanded by Captain Sir John Franklin, a seasoned polar explorer who had already led two previous searches for the Northwest Passage.

However, his final journey to the Arctic would end in tragedy.

Both ships were lost, and all 129 men on board perished. It is the worst disaster in the history of British polar exploration.

Dozens of expeditions were launched to find Terror and Erebus. Many of the objects discovered during these missions are now held in the National Maritime Museum, relics to John Franklin's doomed voyage.

But what really happened to the crew of the Terror and Erebus? Fresh evidence from the shipwrecks discovered in 2014 and 2016 has offered fresh insight, while novels, TV series and archaeological investigations have all attempted to shed light on the crew's final moments.

Find out more about the real history of Terror and Erebus, and discover what the objects left behind can tell us about the crew who never returned home.

Don't lose contact

Sign up to our newsletter to discover remarkable stories from our maritime past, and keep up to date with special exhibitions and events from Royal Museums Greenwich.

In brief: the story of Erebus and Terror

In May 1845 two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, sailed from Britain to what is now Nunavut in Northern Canada.

Explorations of the Arctic coastline had led to great optimism that finding and charting the final part of the Northwest Passage – the seaway linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans – was now within reach.

Explorer John Franklin, who had made two previous attempts to find it, was keen to claim the prize.

By previous standards the Erebus and Terror were powerful and luxurious, with heating systems and vast supplies of preserved foods. In late July, the two ships were seen by a whaler in Baffin Bay, waiting for ice to clear in Lancaster Sound and to begin their journey to the Bering Strait.

It was the last time any of the 129 crewmen were ever seen alive.

After two years without receiving any communication from Franklin’s mission, the Admiralty sent out a search party but without success.

A total of 39 missions were sent to the Arctic but it wasn’t until the 1850s that evidence of what befell the men began to emerge. The exact circumstances of their deaths remain a mystery to this day.

What was life like on board Erebus and Terror?

The men on board the ships of Franklin's expedition faced bitter conditions – in extreme cold, even taking a balaclava off could rip the skin and beard from the chin. The crews therefore prepared as best as they could.

Royal Museums Greenwich curator Dr Claire Warrior pieces together the experiences of Franklin's men:

The short answer is, we don’t know what life was really like. We don’t yet have any of the journals or logbooks that would have been written aboard ship.

But we do have lots of evidence from other sources about what the men might have gone through. Using these, we can come as close as we possibly can to understanding what the crews of Erebus and Terror might have seen and felt.

Expeditions set off in the spring, so that they could get as far as possible before the winter, when their progress was halted.

Unfamiliar wildlife might be glimpsed, such as narwhals (which were called ‘sea-unicorns’), and splashes of botanical life, including vivid yellow poppies.

The Arctic could be a place of freezing fog and heaving seas, and the expedition crews were sometimes at the mercy of the immense pressure of the sea-ice and the unpredictable behaviour of icebergs. It was also, at times, breathtakingly beautiful, with dazzling colours and glowing skies.

Franklin’s ship was trapped in the ice in a remote and desolate area, which Inuit rarely visited, calling it Tununiq, ‘the back of beyond’. They couldn’t rely on local people for meat, clothing, and oil, as other expeditions had. But they had enough supplies for about three years, and British expeditions were experienced at overwintering in the Arctic...

Claire Warrior, Senior Exhibitions Curator

Temperatures outside could drop as low as -48°C overnight and -35°C by day. Conditions on board ship were not necessarily much warmer: previous expeditions reported the officers sitting round in their greatcoats below decks in freezing temperatures. But Franklin’s ships were fitted with a heating system that may have made life a bit more pleasant.

The men were probably inspected every week for signs of scurvy. Sore gums were an early sign, but scurvy can mean that old wounds reopen, teeth loosen and the skin bruises easily.

Expeditions were supplied with lemon or lime juice to prevent it, but it was a constant problem on polar expeditions, as fresh fruit and vegetables weren’t available. Inuit ate their meat raw, which ensured that they got enough Vitamin C.

Making magnetic and meteorological observations would have been a key part of the expedition’s scientific remit, but the men had to do so carefully. Placing cold metal instruments up to the eye could cause the skin to be damaged or even removed, and the men had to hold their breath to stop condensation forming on the glass parts.

Pulling sledges could be difficult, too, if the men were exploring beyond the ship. Even when temperatures outside are -50°C, you sweat heavily; when you stop, the sweat can turn to ice in your underwear.

Frostbite can blister fingers, making the skin incredibly tender, and toe damage is common. The skin becomes very cold and painful, before turning red, then numb and pale as the tissue freezes. If the blood supply is lost, gangrene may set in – the tissue is dead. Amputation may be needed if this happens. Sores can form when, for example, ice forms below the chin after a runny nose.

Taking a balaclava off can rip the skin and beard from the chin in extreme cold.

Hypothermia is always something to be aware of in these kinds of temperatures. It’s particularly important not to get wet. People shiver uncontrollably, become ‘sleepy’ and slur their speech, get amnesia and become confused, and their heart slows. They may then pass out.

Cows, sheep and a monkey - the animals on board Erebus and Terror

The ships started out with cattle, sheep, pigs, and hens to be eaten in the early stages.

The three pets aboard the Erebus were a monkey that Lady Franklin presented to the ship, an old Newfoundland dog called Neptune, and a cat. The monkey was an amusing but annoying thief, Neptune was very popular amongst the crew, and the cat was needed to catch rats.

While the marines and the officers had their own quarters, the crew did not have fixed bed places. They slung their hammocks from the deck beams in the open area forward of the main mast.

A total of 7,088 pounds of tobacco was supplied to the ships to be either chewed or smoked in pipes. The ship had also been loaded with 2,700 pounds of candles to provide light during the long dark winter months.

What happened to Erebus and Terror?

Franklin’s two naval vessels sailed up the Wellington Channel before turning south toward Beechey Island, where they would spend the winter. In the spring, they sailed south down Peel Sound but, off the northernmost point of King William Island, were trapped by the ice flow down the McClintock Channel.

In the spring of 1847, a party from the expedition travelled across the ice to Point Victory on shore and deposited a written record of their progress.

It is thought they reached Cape Herschel on the south coast of the island, filling in the unexplored part of the Northwest Passage. Sir John Franklin died in June that year.

Still trapped in the ice, Erebus and Terror drifted south until Captain Crozier ordered their abandonment in April 1848. Weakened by starvation and scurvy, the 105 surviving men headed south for the Great Fish River. Most died on the march along the west coast of King William Island.

The Victory Point note

In 1859 the sole piece of paper that revealed anything about what happened was discovered. It is often known as the Victory Point Note.

In the margins of this standard Admiralty form was a handwritten message, which said the ships had been deserted on 22 April 1848, having been stuck in the ice since 12 September 1846.

105 officers and crew under the command of Captain F. R. M. Crozier had departed on foot for the Back River (or Back's Fish River as it was then called). The note confirmed that John Franklin had died on 11 June 1847.

The search for Erebus and Terror

Two years on from the last contact with the Franklin expedition, the first of a series of expeditions was launched to find them – or to discover what had happened to Erebus and Terror.

The loss of Sir John Franklin, a British hero, captured the public imagination. Between 1847 and 1880 over 30 search expeditions ventured to the Arctic in the hopes of uncovering the fate of the expedition.

Traces of Franklin’s first winter camp on Beechey Island were found in 1850, but his progress and fate remained a mystery.

The Admiralty dispatched expeditions both overland and by sea, urged by Franklin's widow Lady Jane Franklin, Parliament and the British press.

However, by 1850 there were still no clues to the fate of the crew. The British Government, after much criticism, offered substantial rewards of £20,000 to any parties who could provide news.

Over the course of the next 30 years, news and relics – such as tin cans, snow goggles and cutlery – filtered back to Britain. Many of these are now in the collections of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

Together these objects speak of what happened: the deaths of the entire crew through a combination of factors including scurvy and starvation.

Cannibalism, madness and poisoning - what really happened to the crew of Erebus and Terror?

In 1854, Dr John Rae brought back Inuit stories that the expedition had perished somewhere to the west of the Back River.

It appeared some of the men had resorted to cannibalism, as many bodies were mutilated and body parts were found in cooking pots.

In 1981, over 100 years after the last search expedition returned home, forensic anthropologist Dr Owen Beattie returned to the fate of the crew as part of the 1845–48 Franklin Expedition Forensic Anthropology Project (FEFAP).

Relics and human remains, overlooked by earlier searchers, were collected from sites on King William Island.

The human remains were analysed using modern forensic techniques in an attempt to ascertain what might have caused the death of the crew and to identify which crew members’ remains had been found.

Through Beattie’s research it was found that the amount of lead in the bones of some of the men was exponentially high, leading to the theory that lead poisoning may have been one of the factors contributing to the expedition’s demise.

During later research on Beechey Island, Beattie and a specialised team exhumed and autopsied three remarkably well-preserved crewmen who had died and were buried during the expedition’s first winter in the Arctic.

Examination of tissues collected from the men’s bodies reaffirmed Beattie’s earlier theory that lead poisoning was one of the factors leading to the expedition’s destruction.

Beattie further supposed that the expedition’s tinned food, hailed as cutting edge technology and stocked in abundance, had been contaminated by lead solder used to seal the tins and was the most likely culprit.

Discovering the wrecks of Erebus and Terror

In 2014 and 2016, the wrecks of HMS Erebus and Terror were finally discovered, shedding new light on the much-debated fate of Franklin's final expedition.

Further dives conducted by underwater archaeologists from Parks Canada in collaboration with the Inuit Heritage Trust have revealed even more fascinating finds.

What can these new discoveries from the deep tell us about the fate of the Franklin expedition?