For centuries, Jeanne Baret's name and place in history were largely forgotten - yet she was the first woman to sail around the world, and made important contributions to the field of botany on her voyages.

Hers was an extraordinary life full of adventure, deception and danger, but only now are we reevaluating her achievements as an adventurer and a scientist.

In 1766, she set sail on a voyage to the Pacific Ocean to collect new and exotic plants with the botanist (and her lover) Philibert Commerçon.

Due to women being banned from French naval ships, Jeanne had to disguise herself as a man, which made the journey particularly difficult and perilous for her.

Read on to discover how Jeanne navigated the challenges she faced as a woman in the all-male environment of an 18th-century sailing ship.

Jeanne's background

Jeanne was born in 1740 in the small village of La Comelle in Burgundy, France.

As the daughter of a peasant labourer, she could expect a life of extreme poverty; literacy and life expectancy rates were very low for women of her class and position.

However, in 1760 Jeanne met the man who changed her life – the natural historian and scientist Philibert Commerçon. He was a major figure in the French Enlightenment movement, corresponding with luminaries such as Voltaire and Linnaeus.

The two came from opposite ends of French society, and normally should never have met. What brought them together was a passion for the natural world, specifically for plants.

Commerçon was an early exponent of Taxonomy – the new science of categorising all living things into family groups.

Meanwhile, Jeanne was known locally as a ‘herb woman’. She grew up with traditional folk knowledge of the location, properties and medicinal uses of herbs and plants.

Male doctors, surgeons, academics and chemists traditionally relied on peasant women such as Jeanne to source the plants they needed for their studies and work.

Whatever the circumstances of their first meeting, we know that Jeanne joined the Commerçon household as a servant, and soon began helping Commerçon with his work of collecting, preserving and categorising plant species.

After the death of Commerçon’s wife in 1762, Jeanne became his housekeeper, but their relationship was clearly much deeper and more personal.

Jeanne became pregnant with his child, and in 1764 they moved to Paris – ostensibly to further Commerçon’s career but probably also to escape provincial morality.

Their unconventional relationship was accepted more easily in Paris, but Jeanne still had to give up their son for adoption, and he sadly died within a year.

The expedition

In 1766, Commerçon was offered the opportunity of a lifetime. Louis XV had agreed to sponsor a three-year expedition to sail around the world and identify new colonies and trading opportunities for France.

Commerçon was offered the role of 'Expedition Botanist', to collect new plant species and survey the natural environment.

He was allowed to bring a servant with him, and Jeanne was the natural candidate. Quite apart from their romantic relationship, she was also his scientific assistant and his nurse (Commerçon was troubled by leg ulcers).

The disguise

However, there remained a big problem. Unlike in the British Navy, women were not allowed on French naval ships. So, together, they came up with a plan for Jeanne to join the expedition disguised as a man.

This would put Jeanne in a difficult and potentially dangerous situation as a lone woman in the confined and all-male environment of an 18th-century sailing ship.

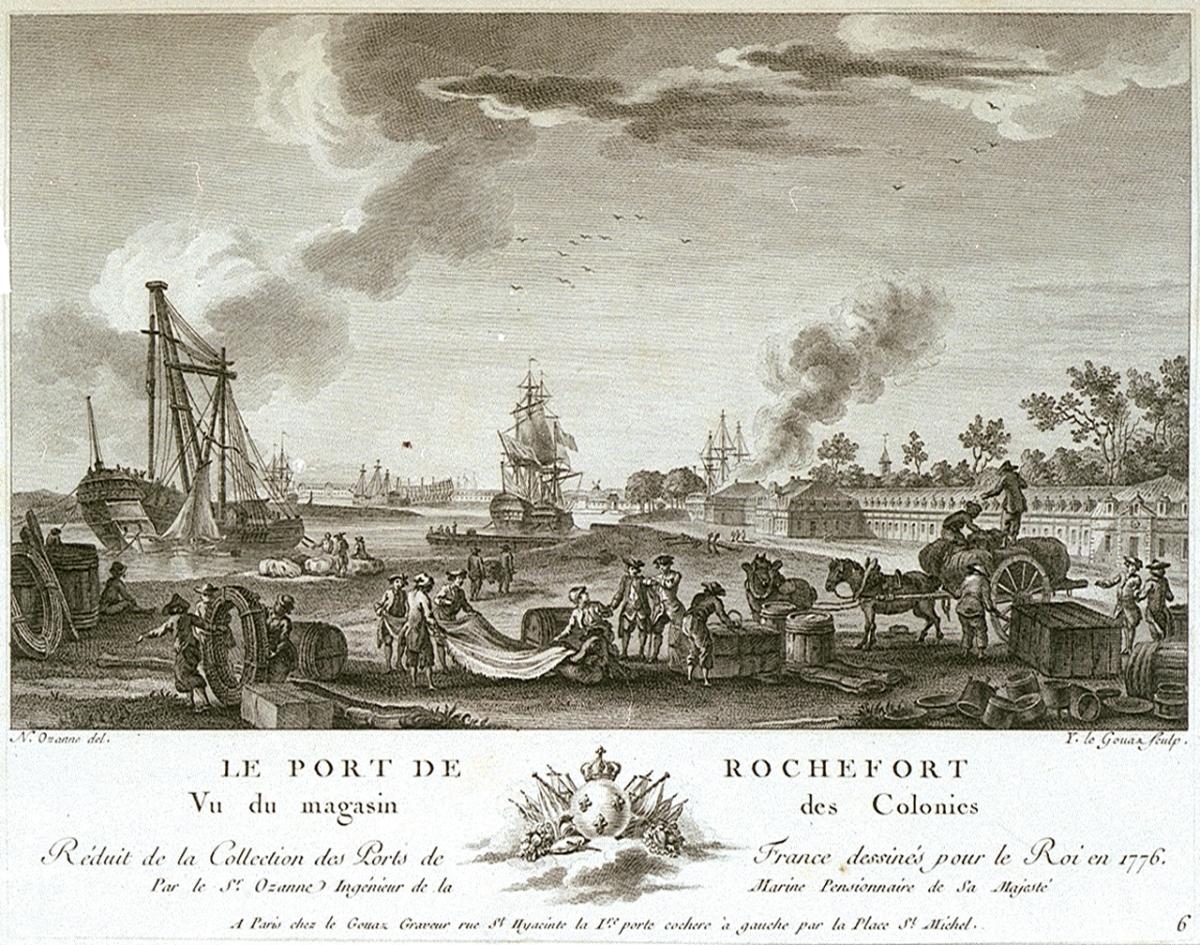

The expedition was leaving from the port of Rochefort on France’s Atlantic coast. Jeanne (now called ‘Jean’ and dressed as a man, with her breasts bound by linen bandages) turned up at the quayside on the evening before departure.

Commerçon pretended they had never met, and appointed ‘Jean’ as his valet.

Keeping her identity secret

Commerçon and Jeanne sailed on L’Etoile - the expedition’s store ship. Due to all their scientific equipment, they were given accommodation in the captain’s cabin.

This came with its own toilet, which should have made it easier for Jeanne to maintain her deception. However, rumours quickly began to circulate that ‘Jean’ was in fact a woman. To deflect suspicion, Jeanne claimed to be a eunuch – captured and castrated by Ottoman forces.

She also had to maintain her deception during the ‘Crossing the Line’ ceremony. This humiliating ritual was commonly forced on crew members crossing the Equator for the first time.

Choosing to remain fully clothed, she was dangled overboard and pelted with dirt from other crew members. However, to maintain her disguise, she couldn’t take her clothes off and wash them afterwards.

South America

In June 1767, L’Etoile reached Rio de Janeiro, where it met up with the expedition’s other vessel, La Boudeuse, and its commander, Admiral Louis Antoine de Bougainville (pictured).

The serious botanical work could now begin. Each day, Commerçon and Jeanne were rowed ashore. Commerçon’s poor health meant Jeanne became his ‘beast of burden’ - journeying into the interior carrying heavy field equipment and bringing back samples of plants, stones and shells.

She earned respect from the crew for her strength, courage and resilience in the most difficult and dangerous circumstances.

One of the species they discovered was a sub-tropical flowering vine, which they name Bougainvillaea after the expedition leader.

The Pacific: the discovery of Jeanne’s gender

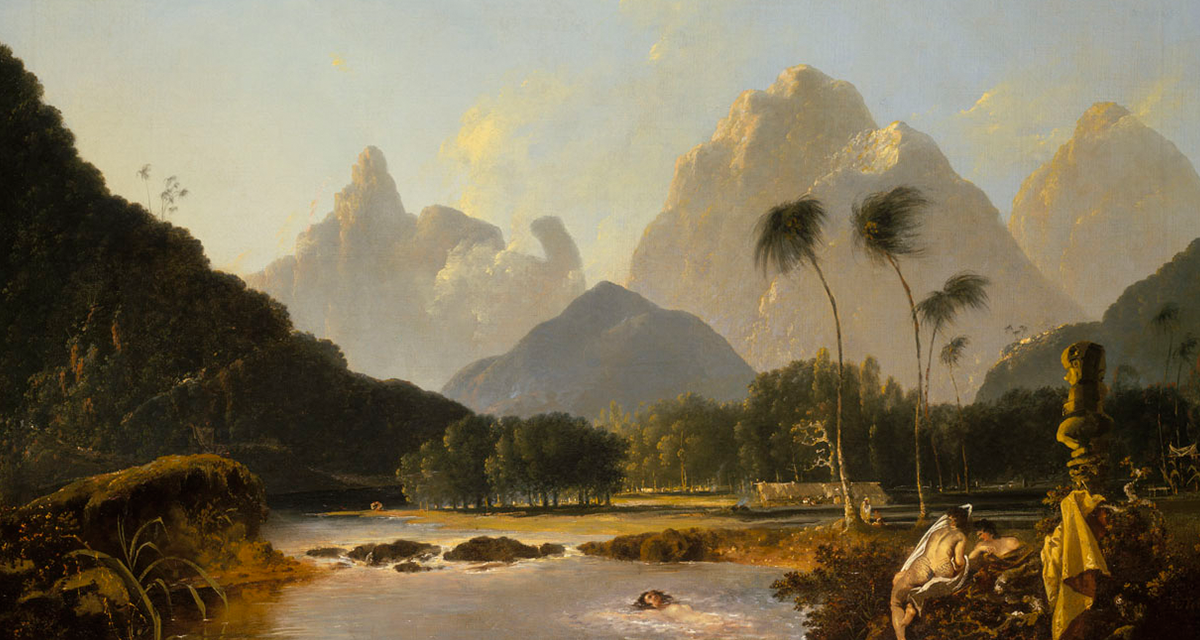

There are different stories concerning the discovery of Jeanne’s true gender. According to Bougainville’s official account of the voyage, this moment occurred when the expedition reached Tahiti in April 1768.

According to him, when Jeanne was rowed ashore she was surrounded and threatened by islanders who cried out that she was a woman, and she had to be rescued by crew members.

This convenient version of events flattered European sensibilities and protected Bougainville from complicity with Jeanne’s deception.

However, there is another more sinister story of Jeanne's gender reveal, which claims Jeanne was confronted and sexually assaulted by crew members in July 1768 on New Ireland (part of Papua New Guinea).

Mauritius

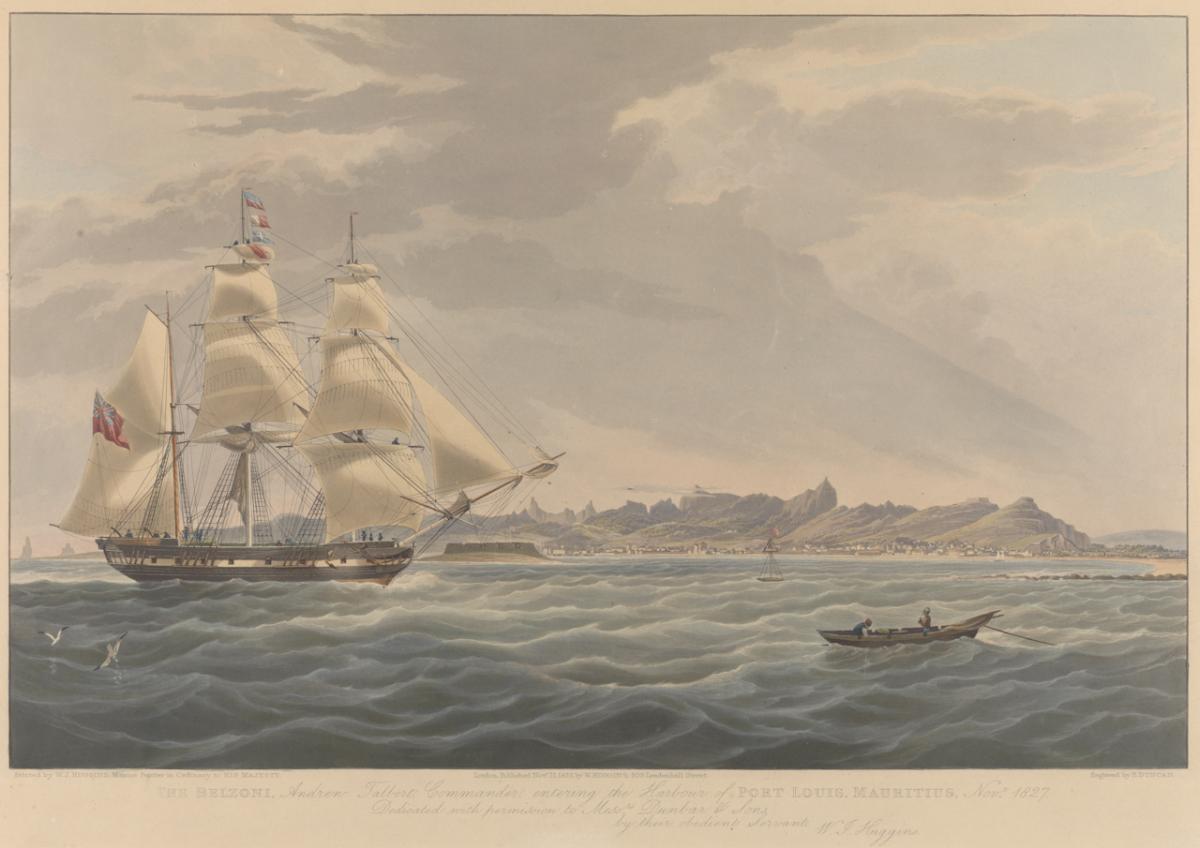

Jeanne was confined to her cabin for the next stage of the voyage. In November 1768, the expedition reached Ile de France – a French trading station that we now know as Mauritius.

By chance, the governor was an old friend of Commerçon and a fellow botanist; when the expedition left, Commerçon and Jeanne stayed behind on the island as his guest.

This meant de Bougainville did not have to return to France with a woman in his crew.

Completing the voyage

Commerçon and Jeanne spent the next three years based in Mauritius, undertaking botanical expeditions to the nearby islands of Madagascar and Reunion.

Jeanne faced another moment of crisis when Commerçon died in February 1773, leaving her alone with little money or support. We know she worked in taverns in the island’s capital, Port Louis, and was fined 50 livres for selling alcohol on Sunday.

In May 1774, Jeanne married a French non-commissioned officer called Jean Dubernat. Together, they returned to France in late 1774. We don’t know exactly when or where Jeanne set foot on French soil, but this was the moment she became the first woman believed to have sailed around the world.

It had taken around eight years. There was no welcoming committee: no one understood or recognised her momentous achievement.

Thanks to money from Commerçon’s will and a French state pension, Jeanne lived out the rest of her life in the village of St Aulaye in the Dordogne with her husband and family members.

She died at home on 5th August 1807 at the age of 67.

What did Jeanne Baret discover?

Working with Commerçon, Jeanne collected over 6,000 plant specimens during her travels and identified numerous new species.

Many specimens made it back to France, and can be found today in museum collections, research institutes and seed banks, adding to our knowledge of the natural world.

For centuries, Jeanne Baret was largely forgotten – sidelined, overlooked and voiceless, like so many women in history. Salacious stories of her deception and exposure overshadowed her very real scientific achievements.

Only in 2012 was a species of nightshade – Solanum Baretiae – finally named after her. And in 2018, the International Astronomical Union named a mountain range on Pluto in her honour. Not a bad legacy for an uneducated peasant girl from a small village in Burgundy!

Article written by Simon Black, Visitor Assistant at the National Maritime Museum.