Royal Observatory Greenwich is Britain’s oldest purpose-built scientific institution.

Founded in 1675, it is the birthplace of modern astronomy, and the home of Greenwich Mean Time and the Prime Meridian.

Today the site holds a unique position as a museum, science attraction and historic site: the national centre for the public understanding of astronomy past and present.

In 2025 the Royal Observatory is celebrating its 350th anniversary. Visit now to discover the site for yourself, and read on to learn about the place that put Greenwich at the heart of global time, navigation and astronomy.

Why is there an Observatory in Greenwich?

"Whereas, in order to the finding out of the longitude of places for perfecting navigation and astronomy, we have resolved to build a small Observatory within our Park at Greenwich upon the highest ground … with lodging rooms for our Astronomical Observator and his Assistant."

This order, given by King Charles II, led to the founding of the Royal Observatory in 1675. Three hundred and fifty years later, it is one of the most important scientific sites in the world. But why was the Observatory built in the first place?

By the 1600s, Britain and other European nations depended on the sea to trade and keep in contact with other nations. However, travelling by sea was hugely dangerous.

This wasn’t just down to the wind and the waves. Once out of sight of land, sailors had no accurate way of finding out their position.

Working out their latitude (their position north or south) using the Sun and stars was relatively easy. However, working out their longitude (position east or west) was much harder. The Royal Observatory was founded in order to find a solution to this 'longitude problem'.

Charles II had been convinced by some of the country’s leading scientists that a national observatory was needed to keep pace with Britain’s seafaring rivals, and that astronomy held the key to finding the 'so-much-desired longitude of places'.

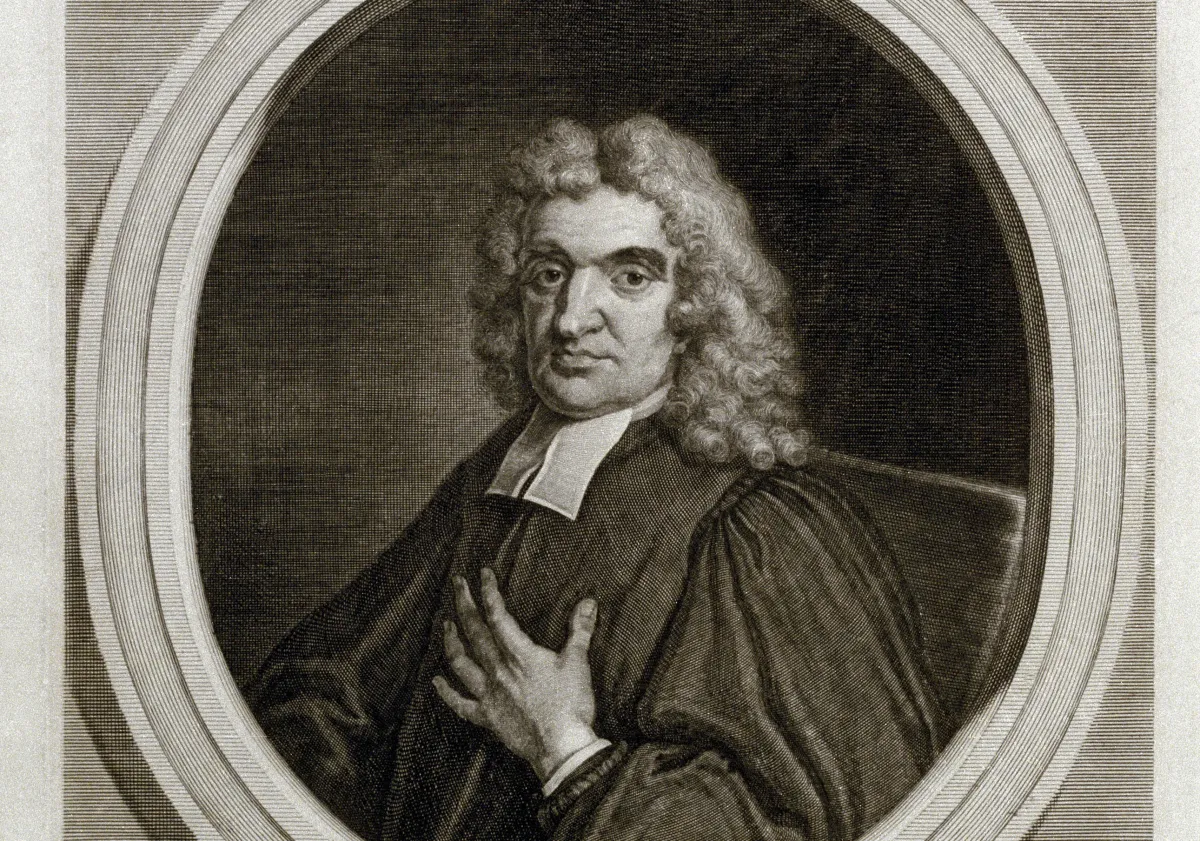

On 4 March 1675 Charles appointed John Flamsteed as his ‘astronomical observator’ – a post later to be known as the Astronomer Royal. A few months later, on 22 June, the king ordered the building of 'a small observatory within our park at Greenwich, upon the highest ground'.

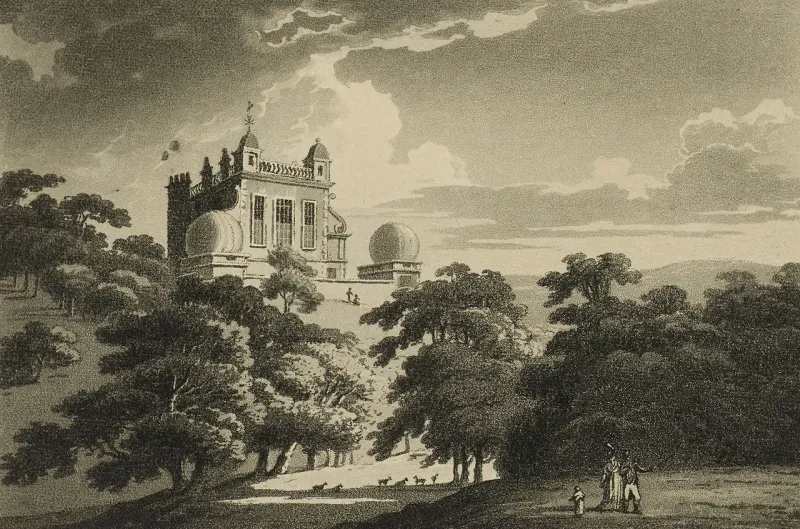

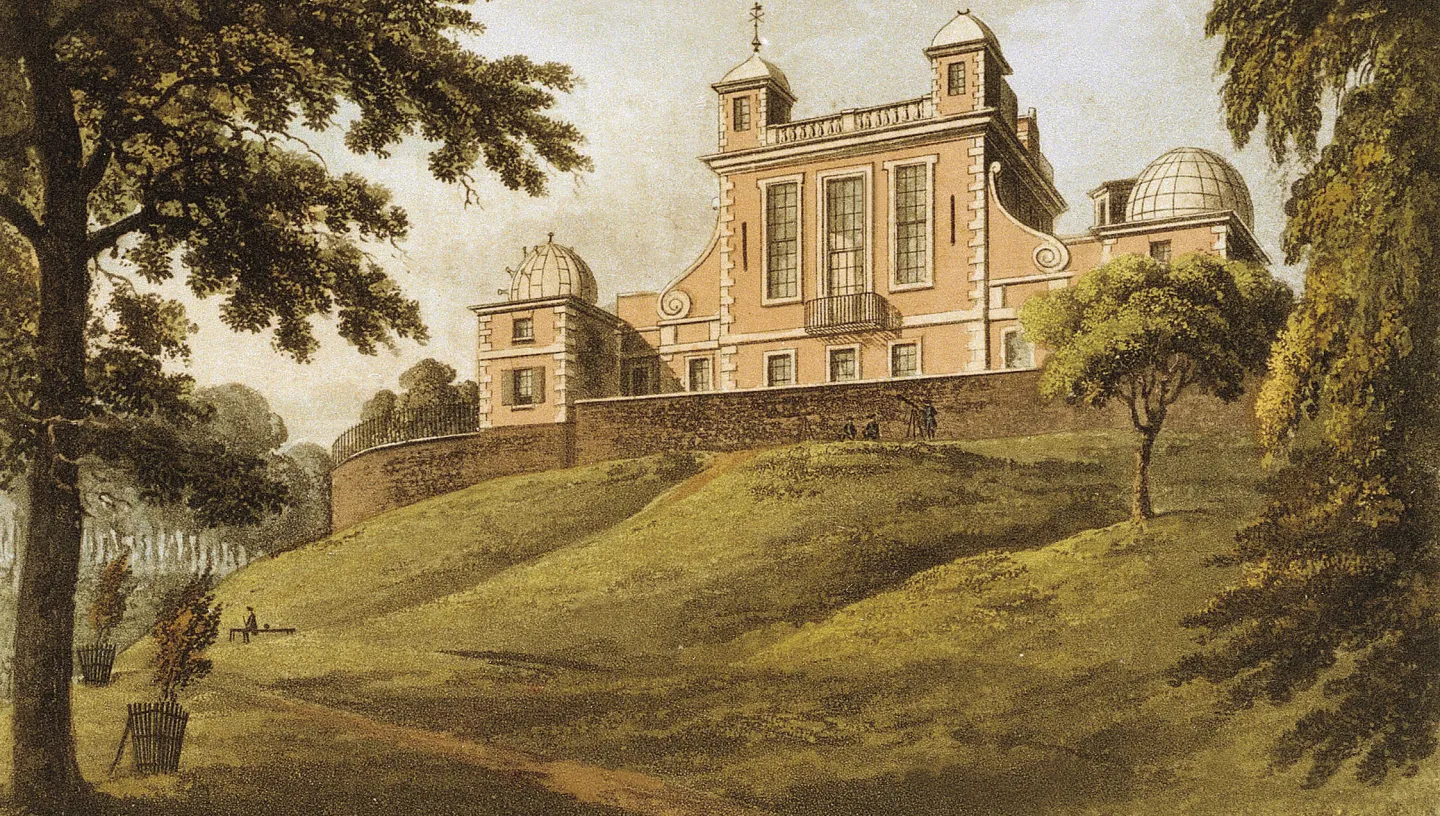

Christopher Wren, best known as the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral, was tasked with designing the Royal Observatory along with his assistant Robert Hooke. Wren’s selection was appropriate: before finding fame as an architect he had been a professor of astronomy at Oxford.

Wren suggested using the ruined Greenwich Castle as the site for the new observatory. The old castle's solid foundations could be repurposed and, because it was located in a Royal Park, the land already belonged to the Crown. The rural hilltop location also made it ideal for astronomical observation while still remaining close enough to London and the city's scientific community.

At 3.14pm on 10 August 1675, Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed laid the foundation stone of the new Royal Observatory. He moved in less than a year later on 10 July 1676.

During the course of the next 40 years, Flamsteed lived within the house which would later bear his name and made over 50,000 observations of the Moon and stars.

The Octagon Room was built above the main living quarters of Flamsteed House. The room's eight-sided shape, high windows and lofty position were designed to provide astronomers with an uninterrupted view of the sky. The high ceilings also allowed the Observatory to install some of the most advanced clocks of the age.

The Astronomer Royal

The Royal Observatory was always intended to be both a working institution and a home for the Astronomer Royal.

Ten Astronomers Royal lived and worked here between 1676 and 1948. Before the 19th century each Astronomer Royal worked alone, with a single assistant, on the meticulous task of gathering data required by other astronomers and navigators at sea.

From the 19th century onwards the Astronomers Royal were supported by a growing team of specialists.

Today, the Astronomer Royal is an honorary title awarded to an eminent astronomer who promotes astronomy both within government and the public sphere.

Click here to learn more about the people who have held the post of Astronomer Royal over the years.

Navigation and the Prime Meridian

As long ago as 1514, it had been proposed that the Moon could be used to measure longitude at sea. The Royal Observatory was founded in order to put this theory into practice, collecting the astronomical data that would enable sailors to find their position at sea.

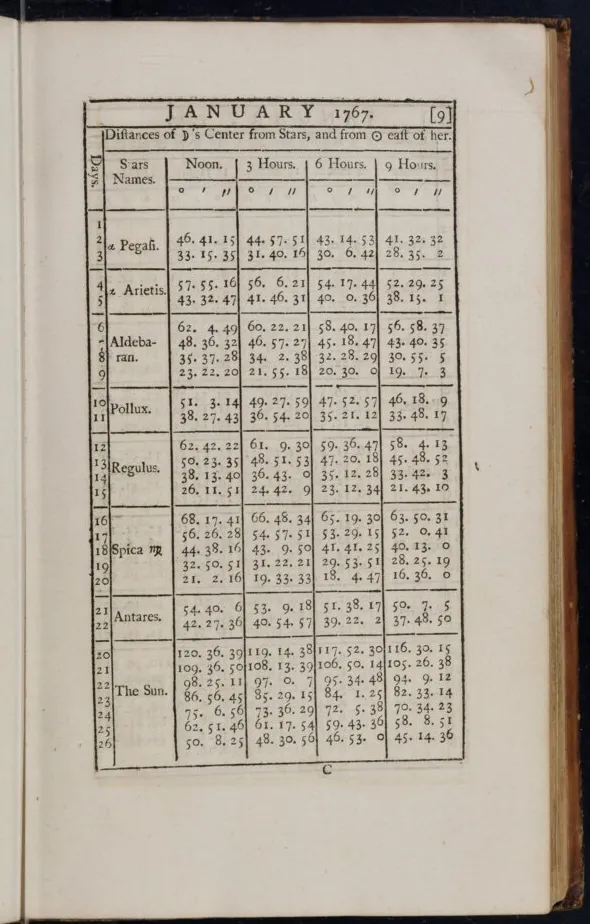

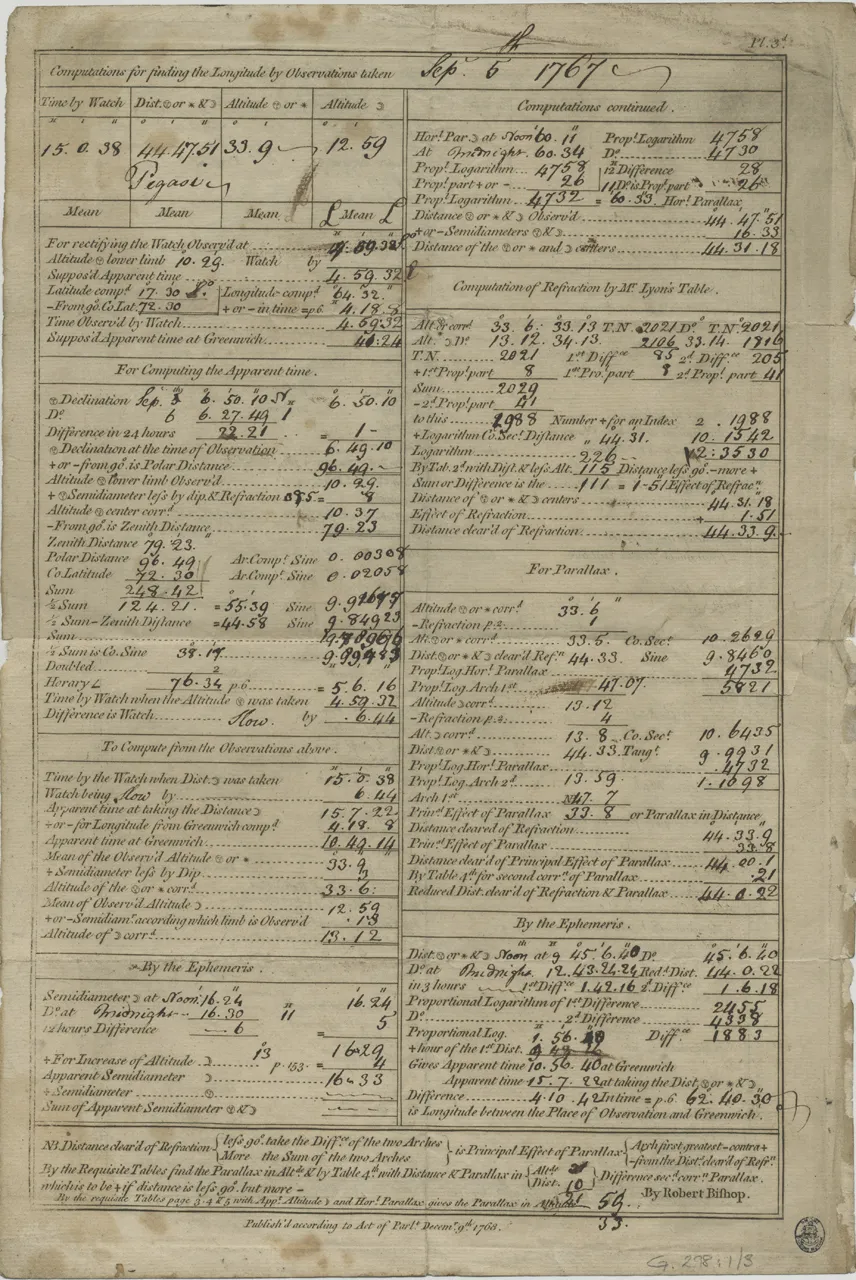

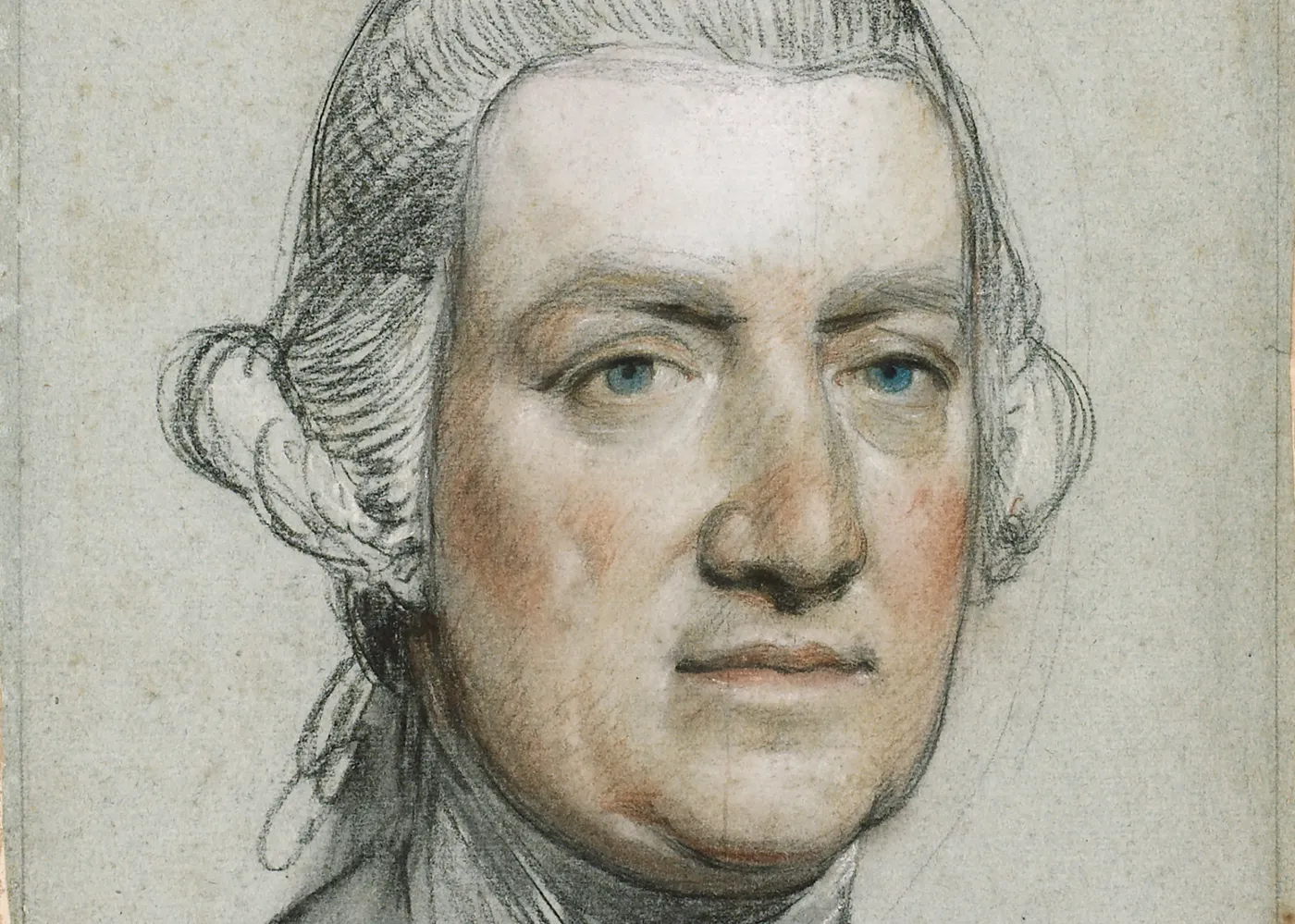

Successive Astronomers Royal and their assistants meticulously observed and plotted the positions of stars in the night sky, as well as the movements of the Sun, Moon and planets. This work culminated in 1766, when fifth Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne published the first Nautical Almanac.

The Nautical Almanac contained a set of tables predicting the position of the Moon during 1767 relative to nearby bright stars. An accompanying handbook helped to explain the complicated calculations needed to measure longitude using lunar observation. Sailors could now use the Nautical Almanac, along with improved navigational instruments such as the sextant, to find their position at sea with far more accuracy than before.

In parallel with astronomers' efforts, clockmakers were also attempting to find ways for seafarers to measure longitude.

To find out how far east or west a sailor was from home, in theory all they had to do was compare their local time with the time back home at exactly the same moment. However, designing a clock that would remain accurate enough during long voyages at sea at first seemed impossible.

By the 1760s however, the English carpenter and clockmaker John Harrison had proved that such a timekeeper was feasible. The groundbreaking 'H4' marine chronometer underwent testing at the Royal Observatory, and Harrison's first four designs are now on display in the Observatory's ‘Time and Longitude’ gallery.

After centuries of uncertainty, by the 1770s seafarers had two ways of measuring longitude at sea.

The Nautical Almanac was updated every year, and became an essential reference tool for seafarers and navigators. The Almanac always gave longitude calculations based on observations taken at the Royal Observatory, but by the 1880s this Greenwich reference line had become a global standard: nearly two-thirds of the world’s ships used charts based on the Greenwich meridian.

That meant that when, in 1884, a conference was held to establish the world’s first ‘Prime’ meridian, the Greenwich meridian was the obvious candidate. Greenwich became the place that defined zero degrees longitude for the world, and the Royal Observatory became famous as the home of the Prime Meridian.

Greenwich Mean Time

Astronomy and time are inextricably linked. By tracking the movement of the stars astronomers can use the sky like a giant clock and ensure accurate time here on Earth.

As the Royal Observatory built a reputation for navigation and astronomy, it also established itself as a centre for measuring and sharing time.

In 1821 the Observatory became the testing centre for marine chronometers used by the Royal Navy. Then in 1833 the Greenwich Time Ball was installed by John Pond, the sixth Astronomer Royal, on the roof of Flamsteed House.

The Time Ball was designed to provide ships in London with an easy way to check their clocks – and it still operates today. At 12.55pm each day the ball is hoisted halfway up its mast. At 12.58 it rises to the top, before dropping down at 1pm precisely.

But accurate time wasn’t just needed by seafarers.

Up until the mid-19th century towns and cities across Britain kept their own ‘local’ time defined by the Sun. There was no unified time for the whole country.

This began to change with the development of the railways. For the first time travel was fast enough for people to notice – and to be confused by – the varying times across the country. Travellers from London to Liverpool for example had to put their watches back 12 minutes on arrival to compensate for travelling from east to west. Railway companies argued that a new ‘Uniformity of Time’ was needed to coordinate the growing network. The Royal Observatory would provide it.

By the 1840s most railway companies had adopted Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) as their standard time, irrespective of local time. Then in 1852 a new electrical clock system was installed at the Royal Observatory, capable of sending time signals via telegraph wires to stations and buildings across the country.

The clock also sent the time to a dial installed directly outside the Royal Observatory, making it the first clock to share Greenwich Mean Time directly with the public. The distinctive Shepherd Gate Clock, with its 24-hour dial, is still found on the wall of the Royal Observatory today.

In 1880 Greenwich time became the official legal standard in Britain, but there was more to come. In 1884 the International Meridian Conference, as well as establishing Greenwich as the Prime Meridian, recommended a new global time zone system based on Greenwich Mean Time. The Royal Observatory found itself at the centre of world time and navigation.

Exploring deeper into space

During the early 19th century, astronomers at the Observatory began to expand their work beyond simply recording the positions of the stars.

To help them understand how changes in air pressure and temperature affected instruments and observations, astronomers started to collect meteorological data. Similarly, collecting data about the Earth’s magnetic field helped them determine whether compasses used for navigation could be affected by these changing forces.

In the 1830s the Observatory site was almost doubled in order to accommodate the new Magnet House.

The building was specifically constructed of materials such as wooden planks and brass nails to avoid any interference with the sensitive magnetic and electrical instruments. The Observatory became part of a network of institutions across Europe that documented change within the Earth’s magnetic field. This research became increasingly important as people began to rely on new technologies such as electricity and telegraphy that were affected by magnetic fluctuations.

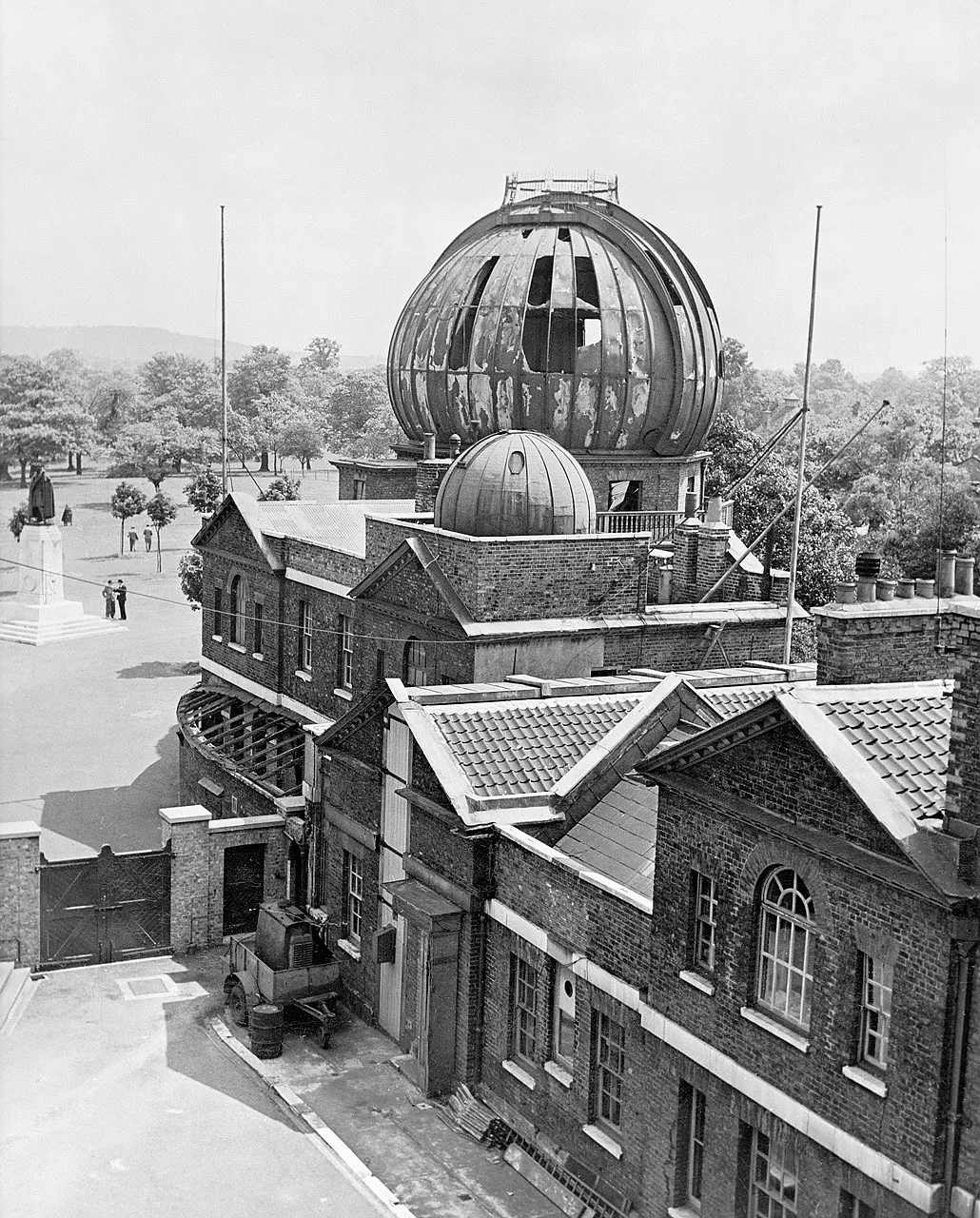

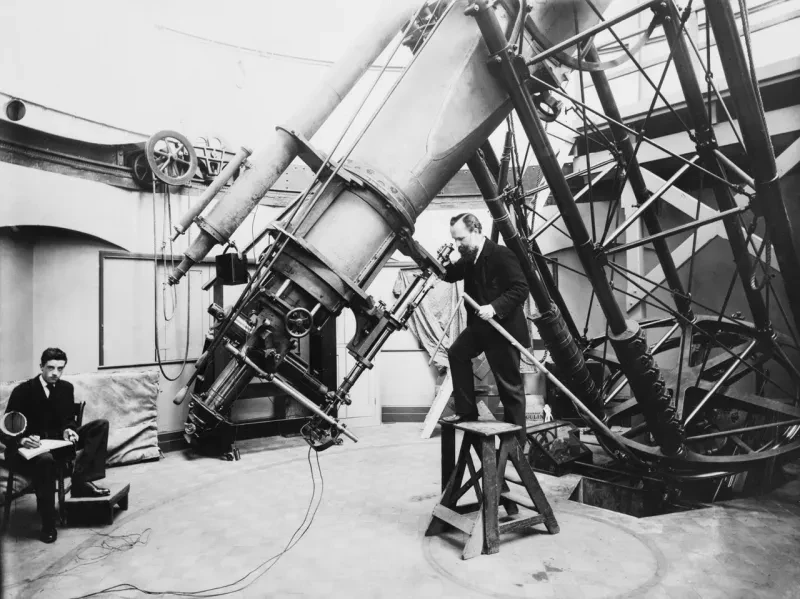

The installation of the Great Equatorial Telescope in 1893 marked another turning point.

A decade earlier, the Eighth Astronomer Royal, William Christie, had realised that other observatories were building bigger and better telescopes. He persuaded the Admiralty to replace the existing telescope with this larger version, keeping the Observatory at the forefront of research into the nature of the universe.

The telescope was used for observing double stars and for spectroscopy (analysing starlight) until 1947 when it was transferred to the Observatory’s new, smog-free site at Herstmonceux Castle in Sussex.

The 20th century and beyond

Despite the expansion of the Royal Observatory site, at the start of the 20th century it was becoming increasingly difficult to observe effectively at Greenwich.

The astronomers found their work hindered by London’s smoke and light pollution. New train lines also caused vibrations and interference to magnetic observations. A move was planned, but delayed by the Second World War – during which the Royal Observatory sustained bomb damage.

From 1948 onwards various departments of the Royal Observatory were relocated to a new site 60 miles away at Herstmonceux.

In 1953, the Greenwich site became part of the National Maritime Museum. The oldest part of the site, Flamsteed House, was opened to the public in 1960, and other buildings soon followed.

2007 saw the opening of the Peter Harrison Planetarium, ushering in a new era for the Royal Observatory as a public attraction.

Today astronomers bring modern astronomy to life through an ever-changing programme of planetarium shows, astronomy courses, school visits and more. By training and inspiring the next generation of scientists, the Royal Observatory is helping to ensure that the future of astronomy will be as exhilarating and surprising as its past.

Time to subscribe?

Sign up to our newsletter for the latest news, offers, and events from Royal Museums Greenwich, including exclusive offers from the Royal Observatory.