Astronomer Royal is a prestigious post in British astronomy.

The role was established in 1675 by King Charles II alongside the founding of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

For almost 300 years the title was awarded to an eminent astronomer who directed both the scientific programme and day-to-day running of the Royal Observatory.

Numerous leading figures in British science, including John Flamsteed and Edmond Halley, held the post.

In 1972 the title became largely honorary and was no longer associated with the Royal Observatory itself. It is awarded to a distinguished astronomer as recognition for their contributions to the field.

The current Astronomer Royal is Michele Dougherty, who was appointed in July 2025.

List of Astronomers Royal

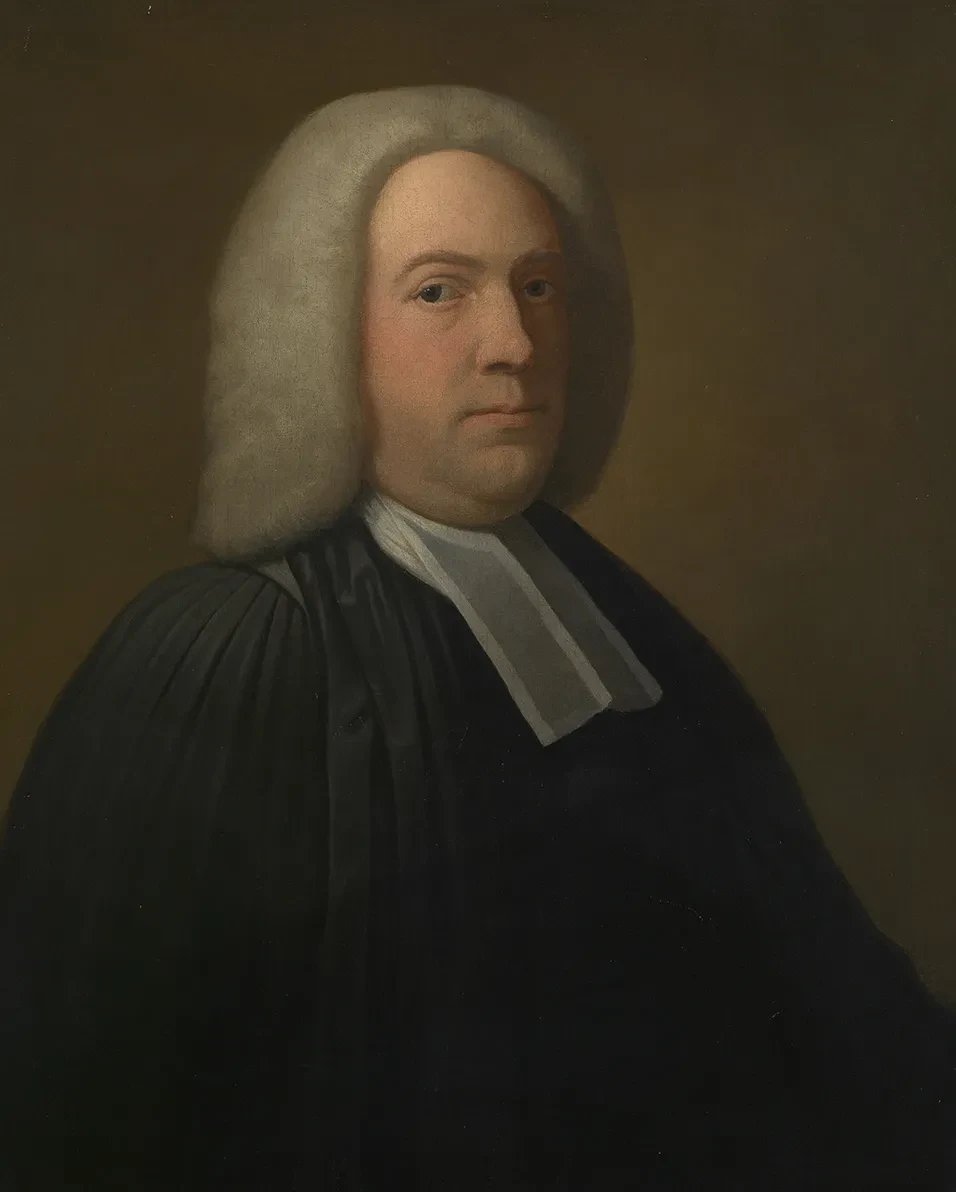

John Flamsteed (1675-1719)

John Flamsteed was appointed ‘astronomical observator’, the position that would become Astronomer Royal, by King Charles II in 1675. He held the position for 44 years.

Flamsteed's task was to create an accurate map of the night sky, which could be used to help determine longitude and improve navigation at sea. The Royal Observatory in Greenwich was founded in the same year to aid him in this task.

During his appointment, Flamsteed played an integral role in establishing the Observatory’s reputation as a pioneering centre of astronomy and timekeeping.

His key works were a catalogue of 3,000 stars, Historia Coelestis Britannica, and the largest and most accurate star atlas that had ever been published, Atlas Coelestis.

However, his later years were mired in controversy over his hesitancy to share his life’s work before perfecting it, which led to Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley publishing an unfinished version against his will in 1712. His works were finally published in full posthumously by his widow Margaret.

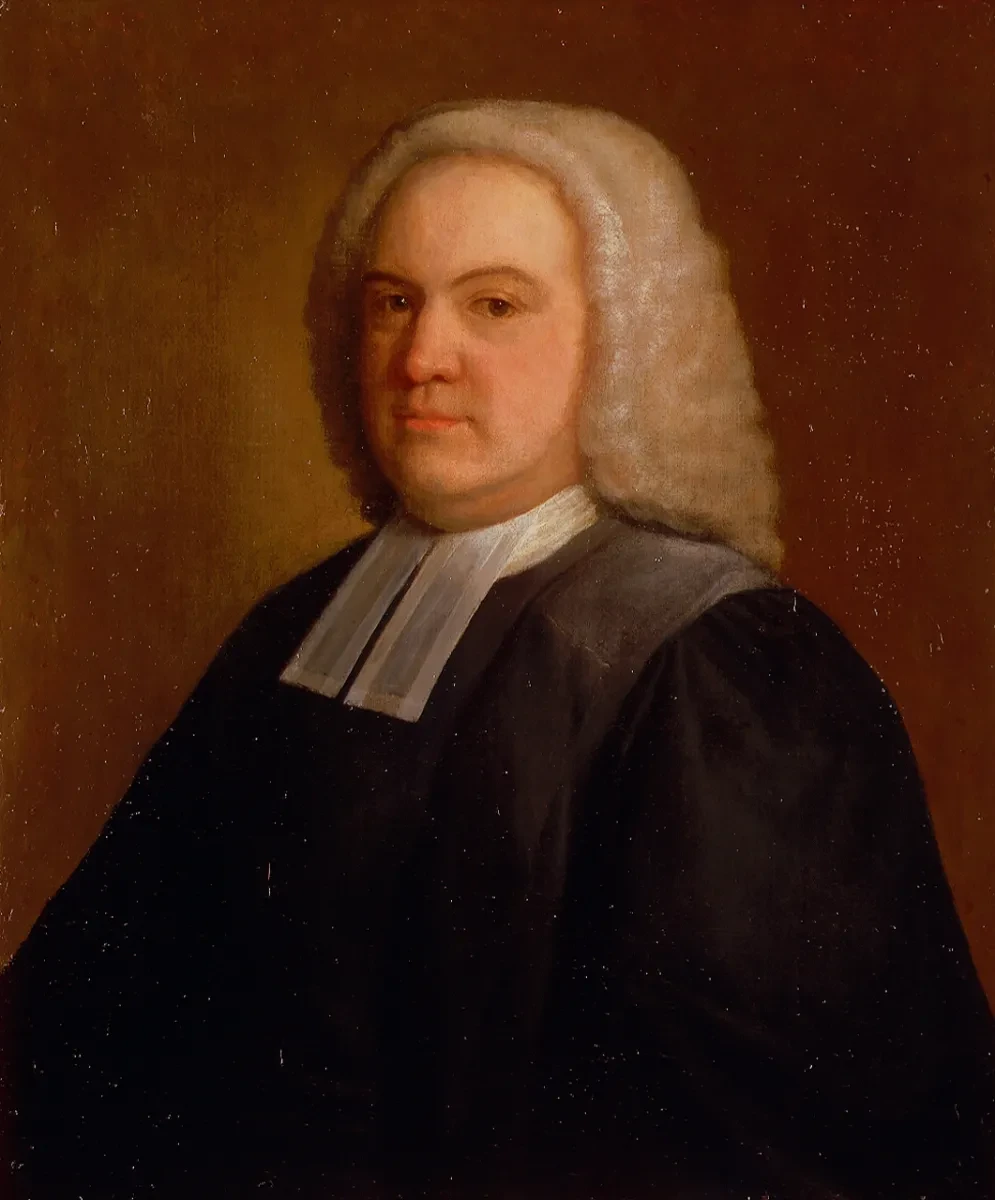

Edmond Halley (1720-1742)

Edmond Halley had a long and illustrious career in astronomy before becoming Astronomer Royal at the age of 64.

His work included creating a 341-star catalogue of the southern skies, helping to develop the theory of gravitation, and sailing as a captain in the Royal Navy to investigate using the difference between true and magnetic north to calculate longitude.

He became Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford in 1704, a post he held for almost 38 years.

In 1705, Halley worked out that comets could make multiple visits to our skies and computed the orbits of several comets. He predicted that a historic comet would return in 1758, and when this turned out to be correct, it was posthumously named ‘Halley’s Comet’.

Halley took over from John Flamsteed as Astronomer Royal in 1720. He re-equipped the Royal Observatory, after Margaret Flamsteed removed the instruments her husband had personally purchased.

To complement Flamsteed’s star catalogue, Halley saw his main task as improving the accuracy of mathematical tables that charted the position of the Moon. However, these measurements lacked accuracy, and although they were eventually published, their limitations soon became obvious.

James Bradley (1742-1762)

James Bradley studied theology at Oxford University for years before developing an interest in astronomy, encouraged by Halley.

Bradley was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1718, and left the church to take up the post of Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford in 1721. Towards the end of the decade he discovered ‘aberration’, when a star appears in a position slightly displaced from its actual position due to the orbital motion of Earth and the finite speed of light.

In 1742 Bradley took over from Halley as Astronomer Royal. He had been making observations of the Moon since 1727, and this would lead him to announce his discovery of ‘nutation’ in 1748, the effect of Earth's 'wobble' on its axis caused by the gravitational pull of the Sun and Moon.

Bradley also studied Jupiter’s diameter and satellites (moons), provided evidence for the theory that Earth orbits the Sun, and calculated the speed of light.

Between 1748 and 1762, Bradley made more than 60,000 astronomical observations which were published posthumously in two volumes.

He also established 'Bradley’s Meridian', which defined 0° longitude in the early editions of the mariner’s book of essential astronomical information, the Nautical Almanac. It was also used as the prime meridian for the first Ordnance Survey (OS) map of Britain in 1801 and remains as the basis of OS maps today.

Nathaniel Bliss (1762-1764)

Nathaniel Bliss was Astronomer Royal for the shortest time, having been appointed two years before his death. However, many of Bliss's observations would become key in solving the problem of longitude.

In the 1740s, Bliss worked at the Earl of Macclesfield’s private observatory at Shirburn Castle, near Oxford, making observations of a comet approaching the Sun. He later worked alongside James Bradley at Greenwich, before succeeding him as Astronomer Royal in 1762.

In April 1764 he made and published observations of the annular eclipse visible from Greenwich, but sadly passed away a few months later in September. Many of the observations Bliss made were considered potentially useful for solving the longitude problem and bought from Bliss's widow by the Board of Longitude.

Nevil Maskelyne (1765-1811)

Nevil Maskelyne was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1758.

In 1761, when sailing to observe the transit of Venus for the Society, he experimented with calculating longitude at sea by observing lunar distances.

In 1763 he published The British Mariner's Guide explaining the experiment, and a year later tested John Harrison's fourth timekeeper’s effectiveness for finding longitude at sea, which he reported as inconclusive.

Maskelyne become Astronomer Royal in 1765. His first achievement at Greenwich was to establish regular publication of The Nautical Almanac. This was first issued for 1767 and disseminated the astronomical tables essential for accurate navigation, especially for finding longitude by lunar distances.

In 1769 the next transit of Venus was successfully observed at various points, including from Tahiti by Captain Cook on his first Pacific voyage, based on Maskelyne's instructions.

Maskelyne also made numerous extensions and improvements to the Observatory’s buildings.

John Pond (1811-1835)

John Pond was elected fellow of the Royal Society in 1807 and became Astronomer Royal in 1811, a position he held for almost 25 years.

Pond is primarily known for his work in modernising the Observatory. He updated and replaced old and damaged equipment and changed working arrangements within the Observatory as a whole, with increased staffing and new programmes of work.

In 1833 he installed the time ball at Greenwich, a large ball on top of the Observatory which dropped at exactly 1pm every day and was used by mariners to check their chronometers (accurate sea clocks). The time ball still drops daily at 1pm.

He also produced a new catalogue of over 1,000 stars with unprecedented accuracy in 1833, before retiring from the Astronomer Royal role two years later in 1835.

Sir George Biddell Airy (1835-1881)

George Biddell Airy was a mathematician and Director of Cambridge University Observatory before his appointment as Astronomer Royal in 1835.

During his tenure at the Royal Observatory Airy replaced and added many significant instruments. This included the altazimuth telescope (1847) and the Airy Transit Circle telescope (1851), which defined the Greenwich Mean Time and the Prime Meridian, 0° longitude

He introduced specialist staff and new departments to the Observatory, including the Magnetic and Meteorological departments in 1838.

Airy also brought in photographic registration to automate recordings, an electric device to time transits, spectroscopic observations to analyse starlight, and instigated a new programme of daily observations of sunspots.

Alongside his work at the Observatory, Airy worked as a scientific advisor to the government, advised on topics such as the railways, bridge, canals, the laying of the transatlantic telegraph cable, the construction of the clock for the new Houses of Parliament (Big Ben) and the creation of a new set of national standards for weights and measures.

Find out more about Sir George Biddell Airy

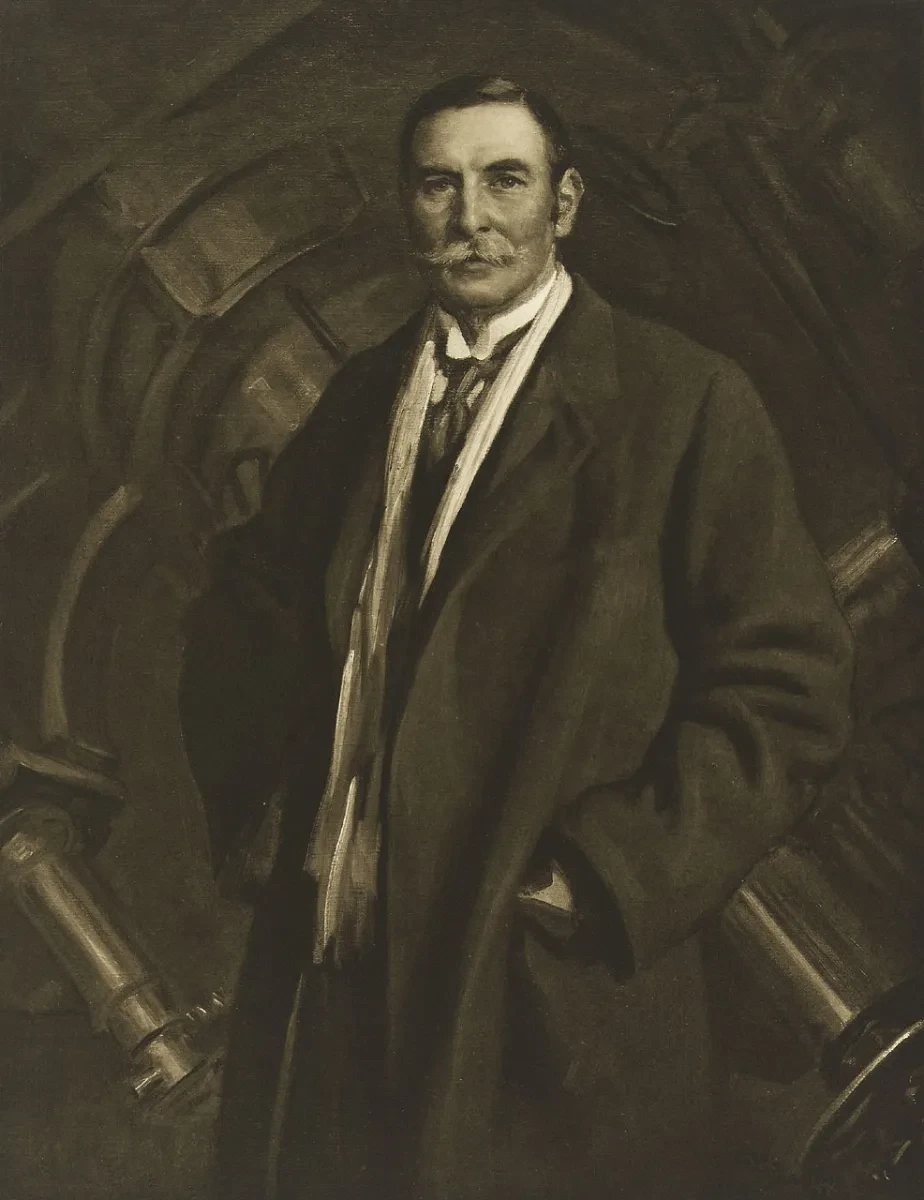

Sir William Henry Mahoney Christie (1881-1910)

William Henry Mahoney Christie was Chief Assistant at the Royal Observatory from 1870 until he replaced George Biddell Airy as Astronomer Royal in 1881.

Under Christie the Observatory not only continued its work in positional astronomy but also became involved with international collaborative projects, such as the Astrographic Chart and Carte du Ciel project of mapping the entire sky in both catalogue and photographic form.

Christie was also responsible for a number of additions to the Observatory site such as the 28-inch Great Equatorial Telescope, and the construction of the New Physical Observatory (known today as the South Building).

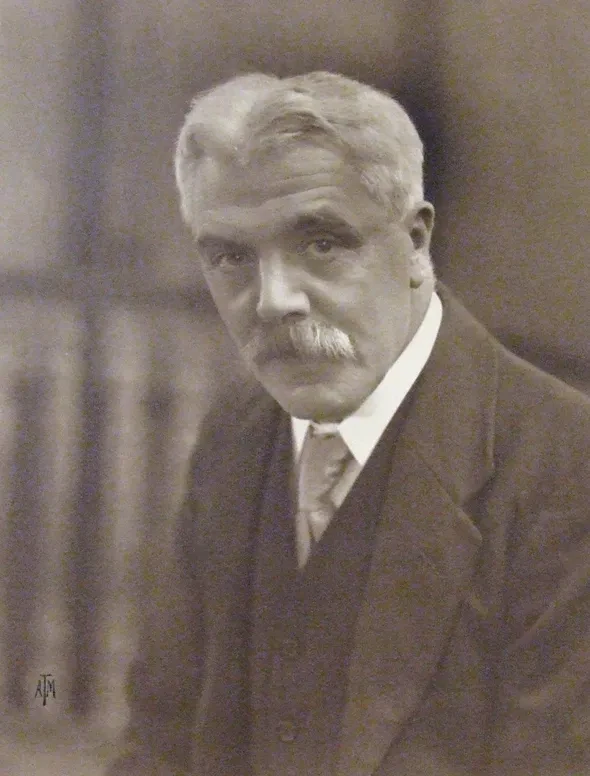

Sir Frank Watson Dyson (1910-1933)

Frank Watson Dyson first worked on problems associated with gravitational theory before becoming Chief Assistant at the Royal Observatory Greenwich in 1894.

His work at Greenwich included managing the Carte du Ciel project, which in turn led him to investigate the proper motion of stars.

In 1906 he moved to Edinburgh Observatory as Astronomer Royal for Scotland and later returned to Greenwich in 1910 to replace Christie as Astronomer Royal.

During his tenure, Dyson's work included studies of the solar corona, stellar parallaxes, and participation in numerous eclipse expeditions. He was also instrumental in organising the famous 1919 eclipse expedition that proved Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Dyson was particularly interested in timekeeping, and brought new accurate clocks into the Observatory, as well as being involved in setting up the Greenwich 'six pips' signal first broadcast in 1924.

After the First World War, Dyson was part of an effort to reestablish international cooperation in science through the International Research Council and the International Astronomical Union.

Sir Harold Spencer Jones (1933-1955)

Harold Spencer Jones was Chief Assistant at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich from 1913 to 1923, then HM Astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope for nine years, before taking up the Astronomer Royal post in 1933.

Under him, the Observatory worked with the Post Office to introduce the speaking clock, and a quartz crystal clock was installed at Greenwich.

Spencer Jones also worked on the colour and temperature of stars and on the Earth's rotation, publishing an important paper in 1939 showing it was not uniform.

In 1941 he announced an improved value of solar parallax and two years later was awarded the Royal Medal from the Royal Society.

It was decided that the Observatory should be moved to a new site at Herstmonceux in Sussex due to increasing light pollution and smog in London, a move which began in 1948 and took place over the next decade.

Spencer Jones was made a Knight of the British Empire in 1955.

Sir Richard van der Riet Woolley (1956-1971)

Richard van der Riet Woolley first joined the Royal Observatory Greenwich in 1933 as Chief Assistant, during which time he worked on meridian astronomy, time service control, double star observation and solar spectroscopy.

Woolley worked as an astronomer at Cambridge Observatory and then as Director of the Commonwealth Solar Observatory Australia, where he studied photospheric convection, the emission spectrum of the chromosphere, and the solar corona.

In 1955 he became Astronomer Royal at a time when the Royal Observatory was still moving equipment from Greenwich to its new site at Herstmonceux.

Woolley made a series of changes, including the installation of the Isaac Newton Telescope – the largest optical telescope in Britain - and initiated summer courses for students at the Observatory. He retired from the post in 1971, but continued to work in astronomy.

Woolley was the last Astronomer Royal to also be Director of the Royal Observatory.

The post becomes honorary

In 1972, the day-to-day running of the Royal Observatory was overseen by a new Director and the role of Astronomer Royal became an honorary title awarded to a prominent British astronomer.

The five Astronomers Royal to hold the title after this change were Sir Martin Ryle (1972-1982), Francis Graham-Smith (1982-1990), Professor Sir Arnold W. Wolfendale (1991-1995), Martin Rees (1995-2025) and Michele Dougherty (2025-present).