During Black History Month Curator Andrew Choong Han Lin shares the story of Marcus Bailey, who served on HMS Chester at the Battle of Jutland

On 30 May 1916 the bulk of the British Grand Fleet left its base in the remote Orkney Islands. Intercepted German communications had alerted the British to a major fleet operation and the Royal Navy hoped to surprise the enemy ships by confronting them in the North Sea with the full might of the Grand Fleet. Among this impressive host of warships was the cruiser HMS Chester. Aboard the ship as part of her 450-strong crew was a cook named Marcus Bailey. Formerly of the mercantile marine, like many men his age he had answered the call to the colours and joined the Royal Navy. It was a decision which would lead to his participation in a terrible battle remembered by the British as Jutland and by the Germans as Skagerrak.

Perceptions of the Royal Navy at the beginning of the 20th Century tend towards an organization that was overwhelmingly –if not exclusively- white. This view is correct to a large degree. The bulk of the navy’s personnel was recruited from the British Isles and prior to World War I the racial demographic of the embryonic Canadian and Australian navies mirrored that of Britain. However, the preponderance of white servicemen should not obscure the valuable service rendered by men of other ethnicities, especially as such men had served in the navy since the age of sail. Born in Barbados, Marcus was by no means the only black man to wear a British naval uniform on 31 May 1916, but he is one of the few about whom some information exists. The continuing commemoration of the centenary of the First World War has presented opportunities to revisit the stories of minorities in the armed services, and Marcus rightly has a place in the National Maritime Museum’s ‘Jutland 1916’ gallery.

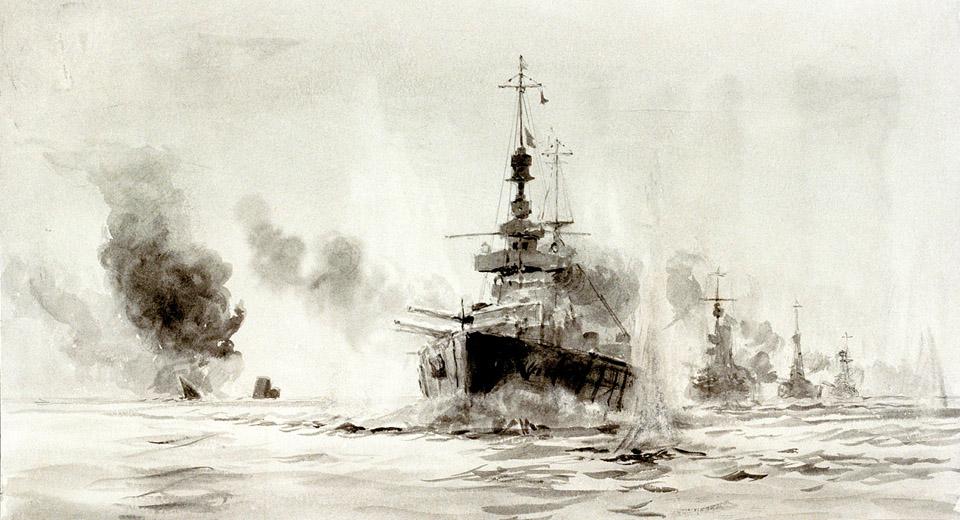

Unlike previous occasions, on 31 May 1916 the British and German sorties resulted in one of the largest and bloodiest naval engagements in history with 8,645 killed and 1,181 wounded. Chester was in the thick of the fight, and at one point found herself heavily engaged by four German light cruisers before being rescued by British battlecruisers. In the unequal combat the ship’s complement suffered heavy losses, with 29 killed and 49 wounded. Writing of the carnage after the action, Lieutenant Phipps Hornby recalled his inspection of the ship that evening; “I looked into the Wardroom. The furniture had been shoved up against the ship’s side and the place was full of wounded. Bloodstained clothing and dressings were scattered everywhere. In one corner lay a torn sea boot out of which protruded a severed leg. The smell was sickening. Outside I came across the Captain’s dog with his paw in bandages.”

Marcus survived the battle uninjured and was doubtless fortunate to do so. In combat, cooks were assigned to ammunition supply or damage control parties or casualty clearance, all of which had their attendant risks. Jutland was his only battle and he eventually returned to a career in mercantile service.