Curator Andrew Choong tries to make sense of the First World War's greatest sea battle.

Involving a total of 279 ships Jutland was fought in 1916 between the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet. Both sides suffered heavy losses in ships and men, but despite the human and material cost the action was a keenly-felt disappointment, with neither side achieving a decisive victory.

The war at sea had developed its own unique character, and for the most part sailors found themselves spending much of their existence within the physical confines of their ships with little or no contact with the enemy for long periods of time. For many, this life of frequent exercises and shipboard routine was abruptly and brutally shattered when the rival fleets met in the North Sea.

Jutland was a complicated battle and for ease of narrative is often described in terms of four phases; the Run to the South (approximately 3.30-4.40pm); the Run to the North (approximately 4.40-6.00pm); the main fleet action (approximately 6.00-8.00pm); and finally the night action (approximately 8.00pm-3.00am on 1 June).

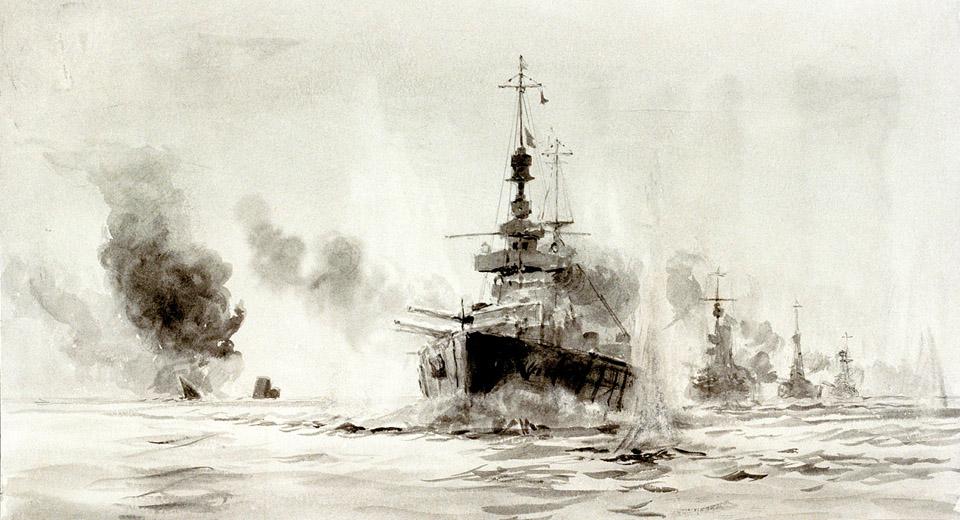

Most of the action was characterised by conditions of poor visibility and confusion arising from inadequate communications. Large numbers of men worked their ships and fired their guns at an enemy they glimpsed only briefly, if at all. The night action which followed was even more bewildering. Vessels appearing suddenly out of the darkness were difficult to identify, and failure to correctly distinguish friend from foe could have lethal consequences.

In terms of losses, the Germans could claim a tactical victory. Fourteen British ships had been sunk and twenty six damaged, as opposed to German losses of eleven sunk and thirty damaged. British casualties (including prisoners) came to 6,945 compared to 3,058 German. Balanced against this the Germans had retreated, effectively conceding the field to the British. On 1 June, one hundred and five undamaged British warships were ready to renew the battle. With only forty combat-ready ships, the Germans did not re-emerge that day.

The High Seas Fleet had failed to critically weaken the Grand Fleet, and the disparity in fighting power would widen in the Royal Navy’s favour as the war continued. Strategically, the battle had little long-term effect other than sowing the seeds of an intensified German U-boat campaign as the only viable alternative to challenging the Grand Fleet. The Royal Navy maintained its dominant position at sea and most importantly was able to continue the blockade that steadily eroded the German war effort.