How did Elizabeth I use gendered symbolism in the Armada Portrait? Dr Kit Heyam explores.

Elizabeth I was constantly aware of how she performed her gender. Subject to sexual rumours about her relationships with her male favourites, and constantly working to distance herself from early modern gendered ideologies which saw women as unreliable subjects to their passions, she inevitably incorporated gender into the crafted symbolism of her portraits.

Among the overtly gendered symbols of the Armada Portrait, like Elizabeth’s virginal pearls, are symbols whose gendered significance is less obvious. This portrait contains many more gendered histories than that of Elizabeth herself.

In 2019, I was privileged to be part of ‘Gendering Interpretations’: a collaborative project between the V&A Museum (London), University of Plymouth, Vasa Museum (Stockholm), Lund University, Leiden University and the University of Western Australia. Building on the earlier project ‘Gender, Power and Materiality in Early Modern Europe’, we worked with a selection of objects at the V&A and Vasa museums to develop a way to uncover these hidden gendered stories. By looking at the role of people of all genders in an object’s life story – and by paying attention not just to the gendered rules of early modern England, but to the people, like Elizabeth, who broke those rules – we revealed rich gendered histories behind the most ordinary of objects. The Armada Portrait is no exception.

The globe

One of the most clear and potent symbols in the portrait is the globe on which Elizabeth’s right hand rests. It’s no coincidence that her fingers are resting on the Americas: this was the focal point of European colonial ambition, which had already seen England clash with Spain, the Catholic enemy whose defeat the portrait commemorates.

The story of Western European invasion and colonisation of the Americas is often told – but what we hear about less often is the way in which that story of colonisation is also the story of the imposition of Western European gender hierarchies and binaries on indigenous American societies.

This story was being written from the moment of first contact between Europeans and the indigenous people of the Caribbean. The first group to encounter Christopher Columbus’s party of invaders were the Taíno people of the Caribbean.

Taíno society and gender

Prior to European invasion, Taíno society didn’t have a very distinct gender hierarchy. Their role of chief was not gender-specific, and women had important political and economic roles.

Spanish colonisation, including the enslavement of Taíno men to labour in silver mines, undermined this relative equality: in particular, as Spanish men married Taíno women, they imposed European hierarchical gender roles.

A similar process took place in other colonised societies: for European men, marrying indigenous women – sometimes consensually, sometimes not – was seen as a key strategy for gaining advantageous trade deals.

And in societies whose understanding of gender didn’t fit neatly into the Western European gender binary, colonisers suppressed other genders and misrepresented them as sexually transgressive.

The pearls in Elizabeth’s splendid headdress, probably from Venezuela, are also implicated in colonialism.

On a symbolic level, though, they also function to emphasise Elizabeth’s chastity. It’s no surprise that Elizabeth chose to use her headdress to communicate this: headwear in the early modern period was a focal point of gendered symbolism and performance.

When late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century writers inveighed against gender nonconformity, their complaints focused overwhelmingly on the head: long, luxuriant hair on people assigned male at birth, and short hair and hats on people assigned female.

Young, fashionable courtiers in particular were often accused of effeminacy – a term which, in this period, suggested excessive desire for women, reflecting (or perhaps causing) excessive attention to one’s appearance and a ‘womanlike’ lack of sexual control.

We can see these courtiers cavorting in the background of Elizabeth I’s sieve portrait.

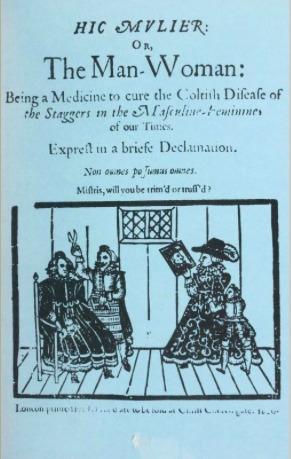

Complaints about women and people assigned female at birth, meanwhile, are exemplified by the anonymous pamphlet Hic mulier: or, The man-woman, printed in 1620, in which writer complained that people assigned female at birth were ‘exchanging the modest attire of the comely Hood, Cawle, Coyfe, handsome Dresse or Kerchiefe, to the cloudy Ruffianly broad-brim’d Hatte, and wanton Feather’.

Here and elsewhere in this pamphlet, we can see the association of ‘women in men’s clothes’ with sexual licentiousness – the hat doesn’t just have a feather, but a ‘wanton feather’ – which reflects the fact that men’s clothes were tighter and more revealing, and that presenting as male was one way to sneak into intimate situations with men.

This kind of gender nonconformity might have incensed some pamphleteers, but – like the long-haired, decoratively dressed courtiers – it was fashionable.

The hunting costume we see in Paul van Somer’s 1617 portrait of Anne of Denmark, complete with ‘broad-brim’d Hatte and wanton Feather’, is a good example.

Anne’s social status, of course, gave her the freedom to evade censure: like many kinds of gendered and sexual transgressions in early modern England, the real problem came when it disrupted the social hierarchy. But the fashionability of this gendered presentation, and the many textual responses to it, tells us that it was widespread.

This means that among the large group of gender nonconforming people, we should make room for individual motivations: for women who were following fashion; women who used male presentation to access economic opportunity; women who wanted to attract other women; and other people assigned female at birth, for whom male presentation felt most comfortable in line with how they saw themselves, and who might today have identified under the trans umbrella.

Of course, while the globe and headpiece of the Armada Portrait have many layers of hidden gendered significance, they are overtly symbolic: included in the portrait to make the viewer notice them and contemplate their meaning.

But this portrait also contains many less obvious symbols. Most crucially, what it obscures is labour: the invisible work that went into producing Elizabeth’s sumptuous outfit and the objects that surround her.

Much of that labour was carried out by poorly paid women, whose work was central to the early modern textile industry, from spinning to ribbon-making.

Beyond cloth, the ‘Gendering Interpretations’ team at Stockholm’s Vasa Museum – home to a vast seventeenth-century warship – have revealed women’s many contributions to maritime history of the kind we see in this portrait, from cannonball manufacture to ship carvings.

Pictures like the Armada Portrait, and all the other wonderful portraits that populate the rooms of the Queen’s House, shape our views of the past – and in doing so, they influence whose past we think about.

Delving deeper into the gendered symbolism of the Armada Portrait reveals that it doesn’t just contain the histories of royalty and national politics: it can also tell us about the histories of people of colour, queer and gender nonconforming people, and working-class people.

We just have to learn how to look for them.