Discover some of the surprising entries recently discovered in the medical records of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital. Are you able to join our transcription project and help to unearth more?

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich was the main clinical site of the Seamen’s Hospital Society (now Seafarer’s Hospital Society), founded to bring relief to sick and injured seafarers of all nations. The HMS NHS: The Nautical Health Service project was launched in 2021 to transcribe the many thousands of entries in the hospital admission registers between 1826 and 1930. The amazing work of the HMS NHS volunteers will provide researchers with opportunities to explore more than one hundred years of medical care provided at the centre of maritime Greenwich.

This blog explores a transformative period in the history of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, when it left behind its floating residence on the River Thames to root itself in bricks and mortar. The transfer of clinical facilities into the vacant Infirmary and Somerset Ward of the Royal Hospital at Greenwich took place in April 1870. The Seamen’s Hospital Society’s annual report presented eight months later stated that the move had enabled it to ‘substantially improve the condition of the patients, and greatly to increase the usefulness of the institution’. It also set in motion changes in the management of the hospital, followed by improvements in the quality of its nursing staff.

Sanitary defects on the Dreadnought

Disquiet about unsanitary conditions on board the Dreadnought and various other issues affecting clinical practice had grown during the 1860s. In its waterfront situation, the ship was often exposed to damage through collisions with passing vessels and swamped by noise from nearby industries. Lack of ventilation, light and space between the decks made conditions unsatisfactory for both patients and staff. Added to this were practical difficulties, including the inconvenience of access, especially at low tide and during icy weather, and an unreliable water supply.

Alongside genuine causes for concern, there was a growing suspicion that the ship was inherently unhealthy, because the timbers had become saturated with ‘septic poison’. Similar charges were later made against the Hamadryad hospital ship at Cardiff, see our blog from May this year. Such reputational damage would have explained why there had been a noticeable preference among some seafarers for admission to land-based hospitals in London. Ultimately, the Seamen’s Hospital Society decided that the best means of promoting the recovery of sick and diseased seamen lay ashore. Henry Turner Lane Rooke (1824-1870), a surgeon on the Dreadnought, was at the forefront of lobbying for the change, and lived just long enough to see it implemented.

The transfer to land

The loan of the Infirmary and Somerset Ward was finally agreed with the Admiralty in late 1869. The five years of negotiations prior to the move were complicated by various debates and rival claims surrounding the future use of the vacant Royal Hospital buildings. Meanwhile, the Seamen’s Hospital Society had also explored the very costly option of constructing a new building on a nearby plot of land purchased from the Commissioners of Greenwich Hospital and the Trustees of Morden College.

The patients of the Dreadnought were brought ashore at high water on 13 April 1870, a date that falls within the pages of the admission register DSH/18. Here the register has details of 18 Greenwich Hospital pensioners (GHPs), who by agreement with the Admiralty, continued to be accommodated in the building handed over to the Seamen’s Hospital Society. The naval veterans had been marooned on the premises, either because they had no families to care for them, or for other reasons which meant they were unable to live outside the institution. Nine of them later feature in the returns for the Sunday 2 April 1871 census of England. One of them was the long-stayer John Williams, born circa 1780 at South Petherton in Somerset. When discharged dead from the Dreadnought on 6 January 1875, he had been victualled for 1,728 days, approaching 5 years.

In Volume IV of Henry C. Burdett’s book ‘Hospitals and Asylums of the World…’, published in 1893, the Dreadnought is classed as ‘double corridor hospital’ because its wards were arranged along both sides of the corridors. When first occupied by the Seamen’s Hospital Society, the two-storey Infirmary building was organised into two main wings. The eastern wing was reserved for medical cases, and the western wing was for surgical cases. Alongside the latter was the Somerset Ward, a single-storey with skylights, specially fitted for severe casualties and out-patients. On the orders of the Admiralty, railings were erected around the grounds, incorporating sufficient space for patients to use for exercise in good weather, of great benefit to those who needed a period of convalescence. From 1873 onwards, the now disconnected main buildings of the Royal Hospital were appropriated for the Royal Naval College.

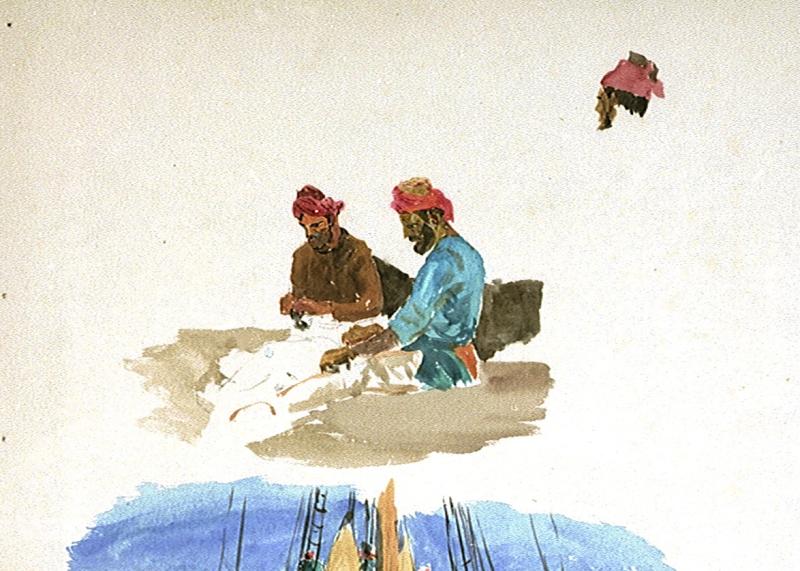

A drawing of Greenwich Hospital, with the Infirmary shown on the right, by Charles White, 1786 (RMG reference: PAH4062).

Reorganisation of staff

A retired naval officer, Commander John Hay Crang (1811-1887), had been employed as Superintendent of the hospital, living on board the Dreadnought with his wife and children. Following the move ashore, the running of what was now styled as the ‘Seamen’s Hospital, Greenwich (late Dreadnought)’ was overseen by a House Governor. Silas Kemball Cook (1818-1874) was the first to be appointed to this role, and from the same office he also continued to work as secretary of the Seamen’s Hospital Society.

On the Dreadnought there had been 3 dormitory style wards containing from 60 to 70 beds each, collectively about 200 beds. Each deck had an allotment of 1 male and 2 female nurses, forming a total of 9. Once on land, the Seamen’s Hospital was able to expand its total accommodation to around 300 patients, formed of 88 wards mostly containing just 3 beds. A report in the British Medical Journal issued on 18 June 1870 discussed how the wards of the Seamen’s Hospital were small, but this had benefits both for the comfort of the patients and for the containment of disease. By the end of the following year, the impact that the increased ward facilities made on nursing costs and general expenditure became clear. A report in The London Daily Chronicle from 27 December 1871 explained that the nursing team had been reorganized and was now made up of 1 male and 16 females, forming a total of 17.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the hospital work of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) had demonstrated the value of female nursing. Nurses had been crucial to patient care on hospital ships, but many of them had been male, and no formal training had been provided. The inadequate conditions on the Dreadnought, including a lack of space in which nurses could ‘retire’, had discouraged applications from experienced female candidates. These issues were now addressed, with a focus on the desire for better standards of nursing, and the related need to offer women better wages.

Firstly, a matron was appointed to recruit and supervise the nursing team. The first woman to work in this capacity was Thomasine Underwood Collins (1833-1908). Collins came from a naval family. Her brother Henry Foster Collins (1818-1847) was educated at the Royal Hospital School at Greenwich, and as second master of HMS Erebus (1826) on the Franklin expedition, had perished in the Arctic. Soon after Collins joined the hospital in 1871, a significant number of the existing nurses were laid off because they didn’t meet the standards that she expected. Collins was later responsible for planning the introduction of trainee nurses known as probationers. Advertisements inviting written applications from ‘respectable women’ who wished to be considered for training to nurse the sick at the Dreadnought Seamen's Hospital appeared in newspapers in 1879.

Changes in recordkeeping

Following the move onshore, changes were also made to how clerks recorded hospital admissions, evident from the scheme of data used from volume DSH/19 onwards. Reflecting the larger size of the establishment, the patient’s location, in terms of wing, floor and ward, was recorded in the ‘where placed’ column. Columns which had previously recorded the height of the patient, and the number of years at sea (with Royal Navy and Merchant Service subdivisions) were dispensed with. The columns containing information on the seafarer’s last ship and voyage (or place of work if a shore casualty) were also reorganised.

Better provision for shore casualties

The increase in capacity of the Seamen’s Hospital, including better facilities for out-patients, was an important development in the context of hospital provision in southeast London. During the months after April 1870, the number of in-patients was maintained at levels similar to those of equivalent periods in previous years, but the numbers of out-patients and local accident cases increased.

Until the opening of the Miller General Hospital at Greenwich in 1884, the nearest general provision had been at Guy’s Hospital in Southwark, about 5 miles away. It was always anticipated that once the Seamen’s Hospital was on shore, it would receive a large proportion of the emergency cases in the locality. In turn, the Seamen’s Hospital Society would be able to argue that it was in the interests of the inhabitants of Greenwich and its vicinity to support the funding of the hospital through voluntary contributions. Its report for the quarter between 30 June and 30 September 1870 appeared in The Daily Telegraph & Courier on 2 November 1870. It stated that there were 143 existing patients at the start of the quarter, the total number of in-patients received during the quarter was 534, and there had been 398 out-patients. It had also received 42 accident cases, many of a severe character, and all requiring immediate attention.

Women and children feature more often in the admission records after 1870. The individuals requiring urgent attention were frequently victims of burns. We can find for example Louisa Isted (initially entered as ‘Emma Oyster’), aged 17, admitted with burns following an accidental ignition of cartridges at Johnson’s ammunition factory on Greenwich marshes. She died of her injuries on 9 March 1871. Relevant articles in the local press mention an inquest held at the ‘Admiral Hardy’ in Greenwich. This illustrates how in the Victorian period, inquests into the circumstances of accidental deaths, attended by a coroner and witnesses, often occurred in public houses.

Future research based on data from the HMS NHS Project will give us a clearer understanding of how the move from ship to shore, with the subsequent reorganisation and expansion, affected clinical practice at the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital. It will also enable us to better trace the development of specialist areas of medical work which enhanced its professional standing. The Dreadnought Medical Service of the Seafarer’s Hospital Society continues to treat seafarers through the medical services of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. Meanwhile, the Infirmary and Somerset Ward buildings discussed above retain the Dreadnought name, but have been repurposed as the Student Centre of the University of Greenwich.

Further reading

Disease in the Merchant Navy; A History of the Seamen’s Hospital Society by Gordon C. Cook, first published by Radcliffe Publishing Ltd., Oxford, 2007.

Hospitals and Asylums of the World: Their Origin, History, Construction, Administration, Management and Legislation by Henry C. Burdett, J. & A. Churchill, London, 1893.

A ground floor plan of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital published as part of the portfolio with Burdett’s survey can be accessed here on the Wellcome Collection website.