In this blog we recall a Victorian explosion on London’s inland waterways which conferred an unusual nickname on the bridge which stood in the way of the blast. The Macclesfield Bridge disaster of 1874 resulted in death and destruction and the passing of an Act of Parliament.

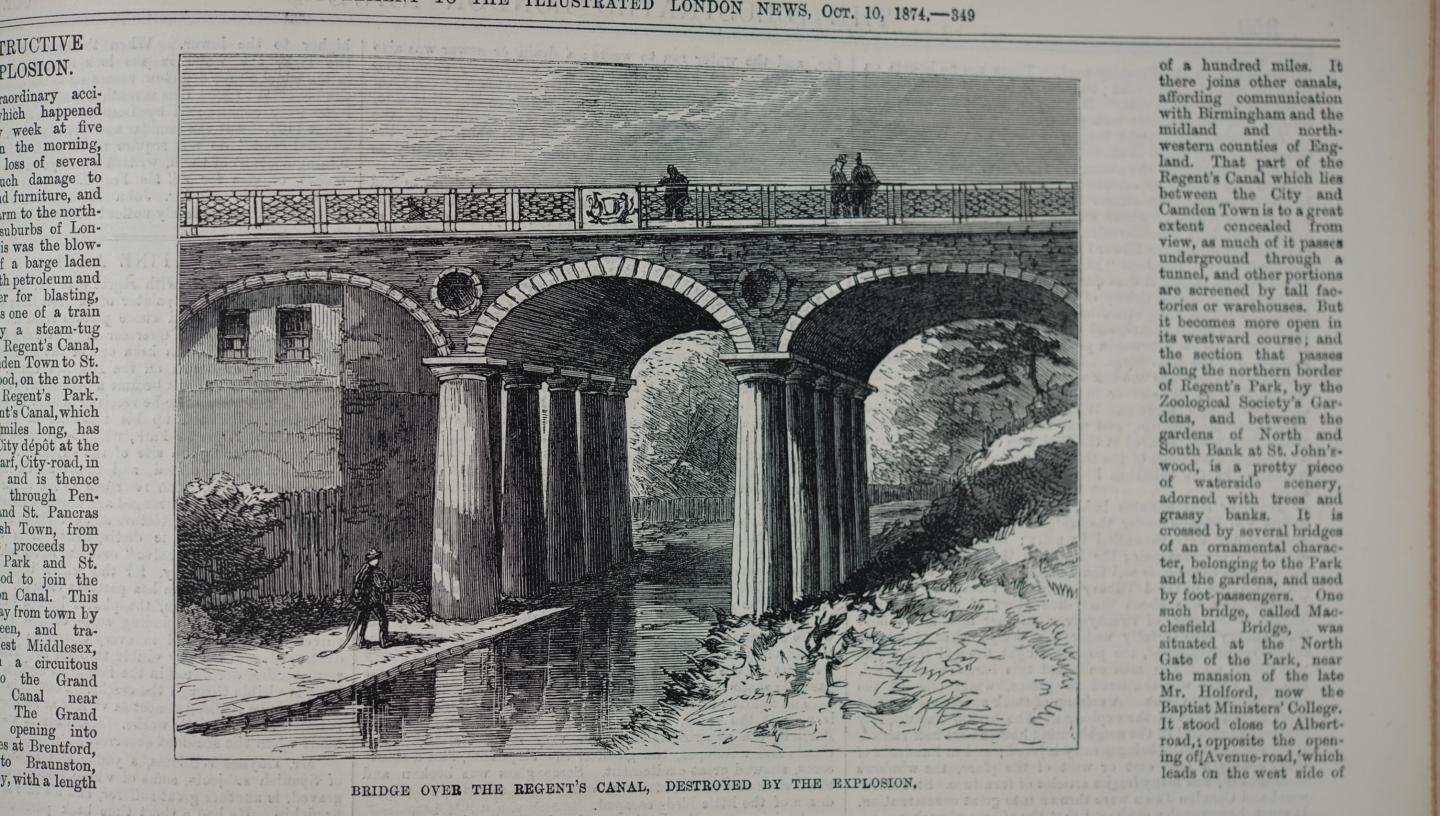

Straddling the Regent’s Canal in London on the northern edge of Regent’s Park are the three brick arches of Macclesfield Bridge. Located a little to the west of London Zoo, this Georgian construction of brick and cast iron has witnessed the passing of two centuries, though it’s not entirely true to say that it has stood still.

Disaster on the Regent's Canal

On the morning of Friday 2 October 1874, a steam tug was pulling a train of six barges along the Regent’s Canal. Among the train were the barges Tilbury and Jane. The Tilbury was carrying a mixed load including sugar, coffee, nuts, petroleum and gunpowder – the last of these was destined for a quarry in the Midlands. The Jane also had a quantity of gunpowder on board.

A few minutes before 5 a.m., as the barges were passing under Macclesfield Bridge, the gunpowder ignited, causing an enormous explosion, blowing up the bridge and reducing its bricks to rubble. A contemporary photograph shows a heap of bricks joining the two banks of the canal and the displaced cast-iron columns projecting out of the canal itself.

The four people on board the Tilbury – three men and a boy – were killed in the blast, and the barge itself was blown to pieces. One of the other barges in the train also sank. Thick smoke ascended from the fire which ensued.

The blast had severed a gas main and a water main. Several houses in the vicinity of the canal suffered damage to their roofs and walls and several hundred other houses up to a mile away to the east and west sustained broken windows and damage to furniture. Milder damage occurred to houses to the north and south.

As it happened, the blast had occurred in a section of the canal which ran through a cutting and this had conducted the air east and west. Had the explosion been on a stretch of canal which ran level with the surroundings, the damage would have been even worse.

The noise of the explosion was heard all over London and as far as ten or twelve miles distant. Animals housed in that part of the zoo nearest the canal were frightened. The Illustrated London News noted that ‘The elands and antelopes, the giraffes, the elephants, and a rhinoceros, showed great excitement.’ Mercifully, no dangerous animals were set free, but the wire of one of the aviaries was damaged and some small birds escaped.

The Illustrated London News (ILN), which covered the story, described the experience of the explosion thus:

The sensation was that of a sudden shock and lift, and then a perpendicular fall, quite unlike the vibration caused by a passing railway-train in a cutting near one’s house. The sound, which followed one or two seconds later, was a single sharp bang, like that of a huge bombshell, with a rolling clatter of echoes.

Some who lived along the railway line thought that perhaps a locomotive had exploded or that two locomotives had collided head-on. Those very close by, such as in Albert Road (now Prince Albert Road) near the junction with Avenue Road and some streets behind in St John’s Wood, felt it more violently. The ILN reported that:

Not a few were fairly tossed out of their beds by the force of the shock, which really amounted to an earthquake in that part. Women and children rushed out of the houses, screaming for help, some in their night-dresses, others wrapped in blankets, and were not easily pacified by those of cooler mind whom they met.

The Aftermath

It was not long before the police and fire brigade arrived on the scene and were joined by some Horse Guards based at Regent’s Park. The grisly task of searching for the victims began. The first two, the boy on board the Tilbury, and William Taylor, a labourer on board the same barge, were found first, while Charles Baxton, the Tilbury’s steerer, was found at around four that afternoon, under a different barge. All three were taken to Marylebone Workhouse.

By the afternoon of the following Tuesday, the canal had been cleared of the bridge and barges, and was usable once again.

The bridge itself was rebuilt using what could be salvaged, together with some new bricks to fill the gaps. The reconstituted Macclesfield Bridge was bestowed with a new nickname: ‘Blow Up Bridge’.

The year after the disaster, Parliament passed the Explosives Act 1875, which regulated the manufacture, storage, sale and transportation of explosives.

The Caird Library has print and electronic access to The Illustrated London News (ILN), which covered the Macclesfield Bridge disaster in its issue of 10 October 1874. The images of the bridge featured here come from that issue. The image of the rhinoceros at London Zoo comes from the ILN of 23 March 1872. The print copies of ILN can be ordered to view in the Caird Library Reading Room via the Library catalogue.