This blog looks at the entertaining diaries of James Anthony Gardner, written on his passage to New South Wales in 1829

There are many journals in the Caird Library & Archive's collection, but few are as entertaining as James Anthony Gardner's account of his voyage to Australia in 1829 (RMG ID: JOD/187/1-2).

Born in 1805, six weeks after Nelson's victory and death at the Battle of Trafalgar, Gardner came from a long line of naval ancestors. His great grandfather, also James Anthony Gardner, served as lieutenant alongside Captain (later Admiral) Francis Geary (1709-1796) in the Culloden in 1747-8. His grandfather, father, uncle and at least two of their cousins all served in the Navy.

Gardner's family also had a talent for writing. His father's naval memoirs were recognised for their literary value and published, posthumously, by the Navy Records Society in 1906. Gardner's father - also called James Anthony Gardner - first went to sea at the age of five as his own father's servant on the Boreas (1774).

Despite that early beginning, a 'blameless record' and good connections, Commander Gardner's career did not advance beyond the rank of lieutenant but his career was, if not exalted, colourful. As an ordinary in the Panther, he helped save some of the crew of the Royal George, and took part, after the relief of Gibraltar, in Lord Howe's action with the combined fleets of France and Spain on 20 October 1782.

Gifted, as he states himself, with a good memory Commander Gardner decided to write his 'recollections' primarily to 'amuse my family'. The editors, acknowledging that Gardner's stories are of little value historically, argue that 'the interest which attaches to his "Recollections" is entirely personal and social; we have in them sketches roughly drawn, crude, inartistic, and perhaps on that account the more valuable, of the life of the time'. In a subsequent publication, Christopher Lloyd, who served as Professor of History at the Royal Naval College in Greenwich between 1962 and 1966, described Gardner as the 'literary counterpart of Rowlandson [the satirical artist Thomas Rowlandson]' who had 'an eye for detail and a natural turn of phrase that any professional novelist would envy'.

It is this eye for detail and talent as a raconteur of life at sea that the younger James Anthony Gardner seems to have inherited from his father.

The voyage

The two volumes of his journal in the Caird Library describe the events on board the merchant ship Percy as it sailed from Gravesend to Sydney, via the Cape of Good Hope and Île Saint-Paul in the Indian Ocean. Gardner had married Isabella Barrington Haswell the previous year at the age of 22. By his own account, the voyage on which he was about to embark was primarily for economic reasons:

'I was proceeding to Sydney - like many others; for lack of employment, the stagnation of trade, cutting down of placements rendering a step of this kind absolutely necessary.'

He had initially got a job as clerk on board the 'Lady Rabbitwood' – almost certainly the Lady Harewood (1791) - a prison ship transporting male convicts to Tasmania, then Van Dieman's Land. He joined the ship on 22 March at Deptford but, by the time he had spent a couple of uncomfortable nights in a hammock in an apartment measuring just four foot square, he determined to secure a berth on another ship. His wife, refusing to allow him to leave without her, joined him at Sheerness, and on 24 May they embarked on the Percy at Gravesend.

The crew

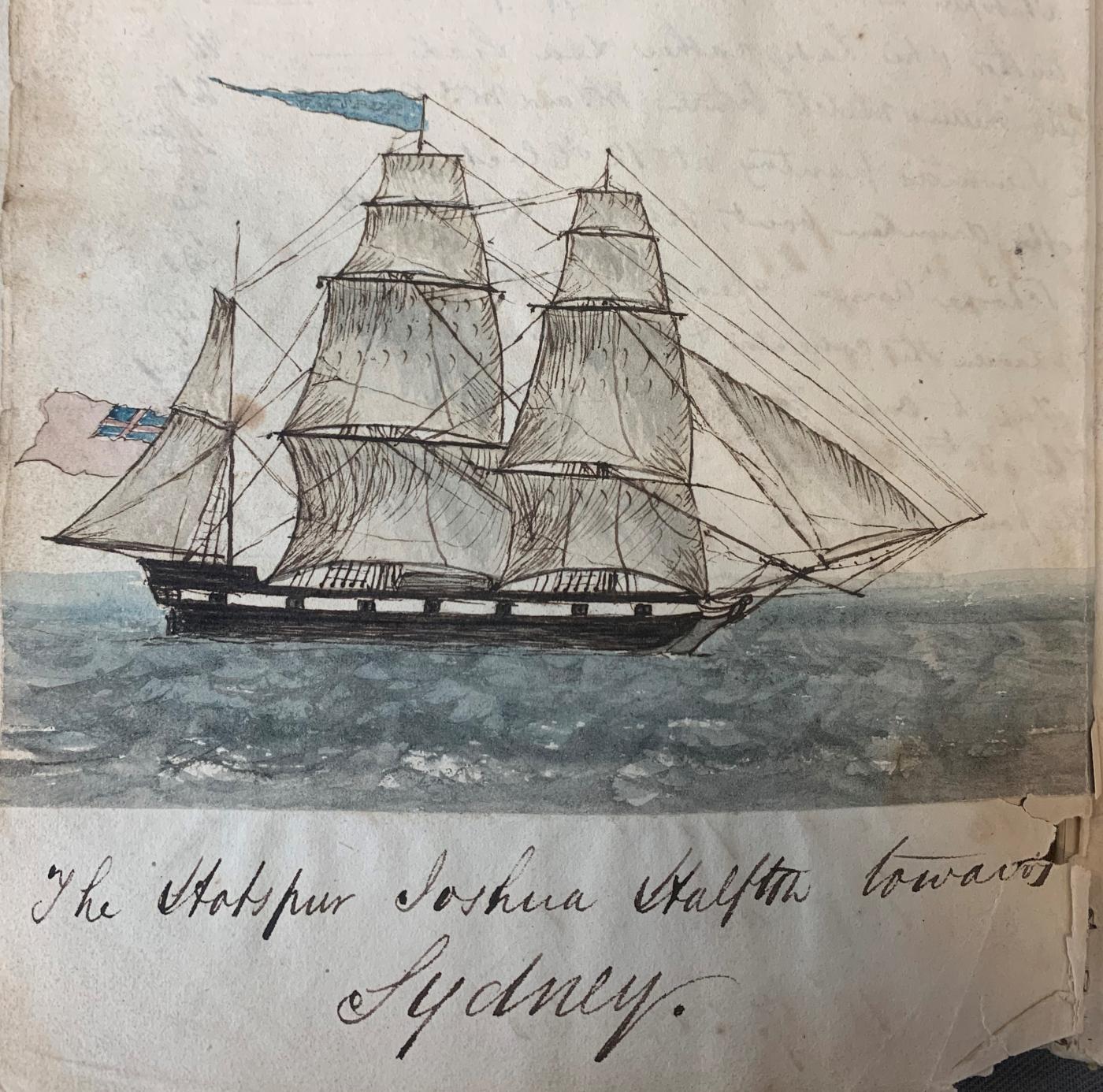

The Percy, named the 'Hotspur' by Gardner in his journal after the fourteenth-century English knight Henry Percy, was skippered by Josiah Middleton. Middleton, renamed Joshua Halfton by Gardner, is a Yorkshireman 'bred at sea' and 'about forty or forty five, of a sallow coarse, weather beaten, gun powder, complexion, with two dark penetrating eyes, sunk deep in his forehead'.

The ship was manned by a motley crew including: Mr Grant, the pilot; John Freeboy, the first mate – a 'chubby little cubbage-faced personage who … understood as much about navigating a ship as a costermonger'; Mr Strong, the second mate – 'a regular Long Tom Coffin [a derring-do character from James Fenimore Cooper's 1824 novel The Pilot], late of HM Navy, but dismissed for striking a Greek pilot at the helm'; William Clinch, the steward; a cabin boy called William Harrington or 'carrotty Tom'; 'Carpenter Sloth', a 'grumbling chips' whose wife, we are told, had 'eloped with a snob'; 'Table Cloth Jack', who was good friends with Freeboy and a 'hell of a fellow for lushing'; and the cook, a 'six foot two Bermudian Black as strong as the devil'.

The passengers

We are told little about the passengers on board other than a family in steerage – Mr Burge, 'a dapper little fellow with a continual smirk, on a most cadaverous, countenance', Mrs Burge, 'a lady on the wrong side of thirty with an unusual twist of the nose, + a brick dust complexion and small twinkling grey eyes', and 'two tender youths – the hopes of the family [who] appeared to be initiated in all the low slang of London'.

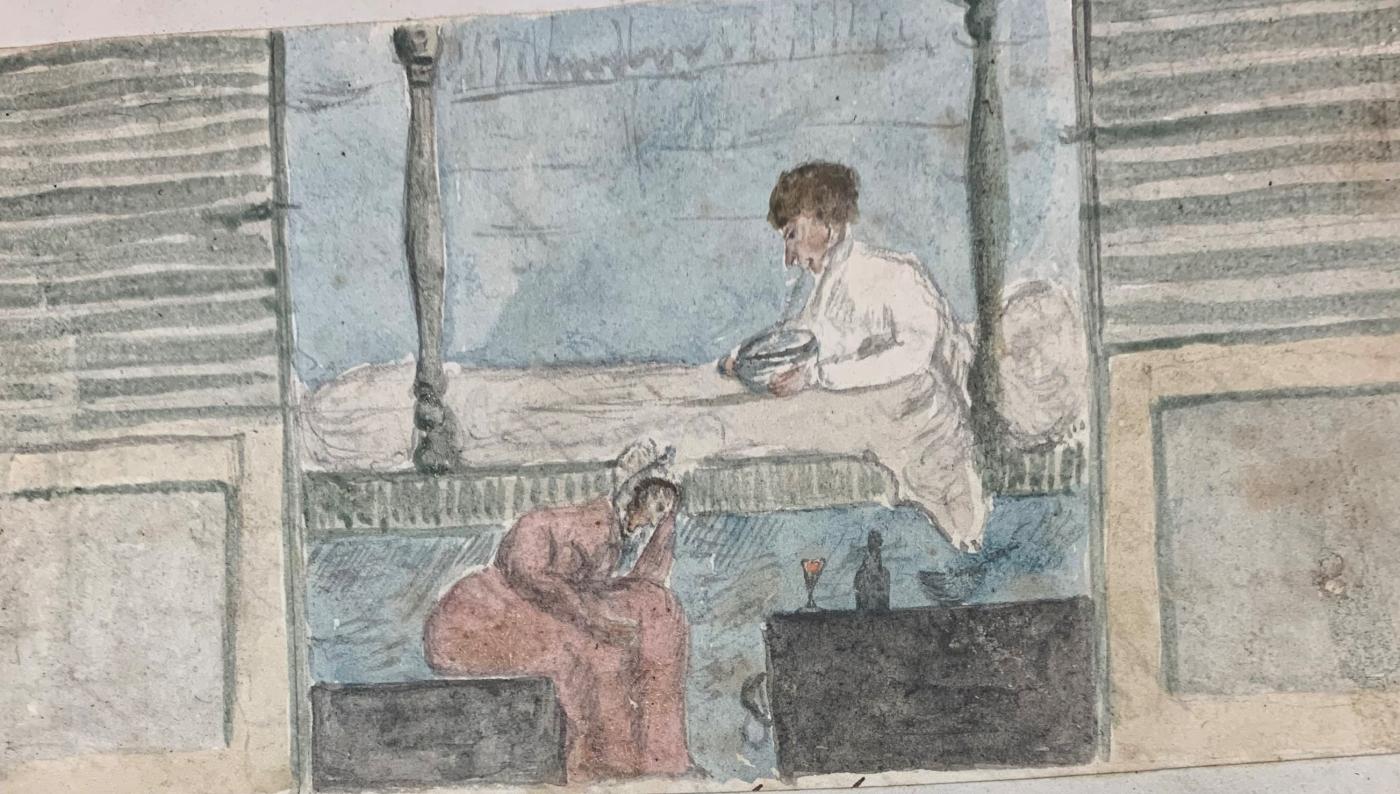

The Burge family seemed intent on getting as drunk as they possibly could throughout the entire voyage, but where they were obtaining their grog remained a mystery – for a while at least. Gardner includes a sketch of Mrs Burge during one bout of drunkenness when, after a disagreement with her husband, she received a 'tremendous facer' from him which sent her 'stern first' down the hatch.

The drunken behaviour continues, despite a written apology from Mr Burge and a promise to amend his behaviour. Finally, a full-scale formal trial on board reveals that Freeboy, the first mate, has been furnishing the Burges with brandy he's been siphoning off from barrels in the 'Hotspur's' store.

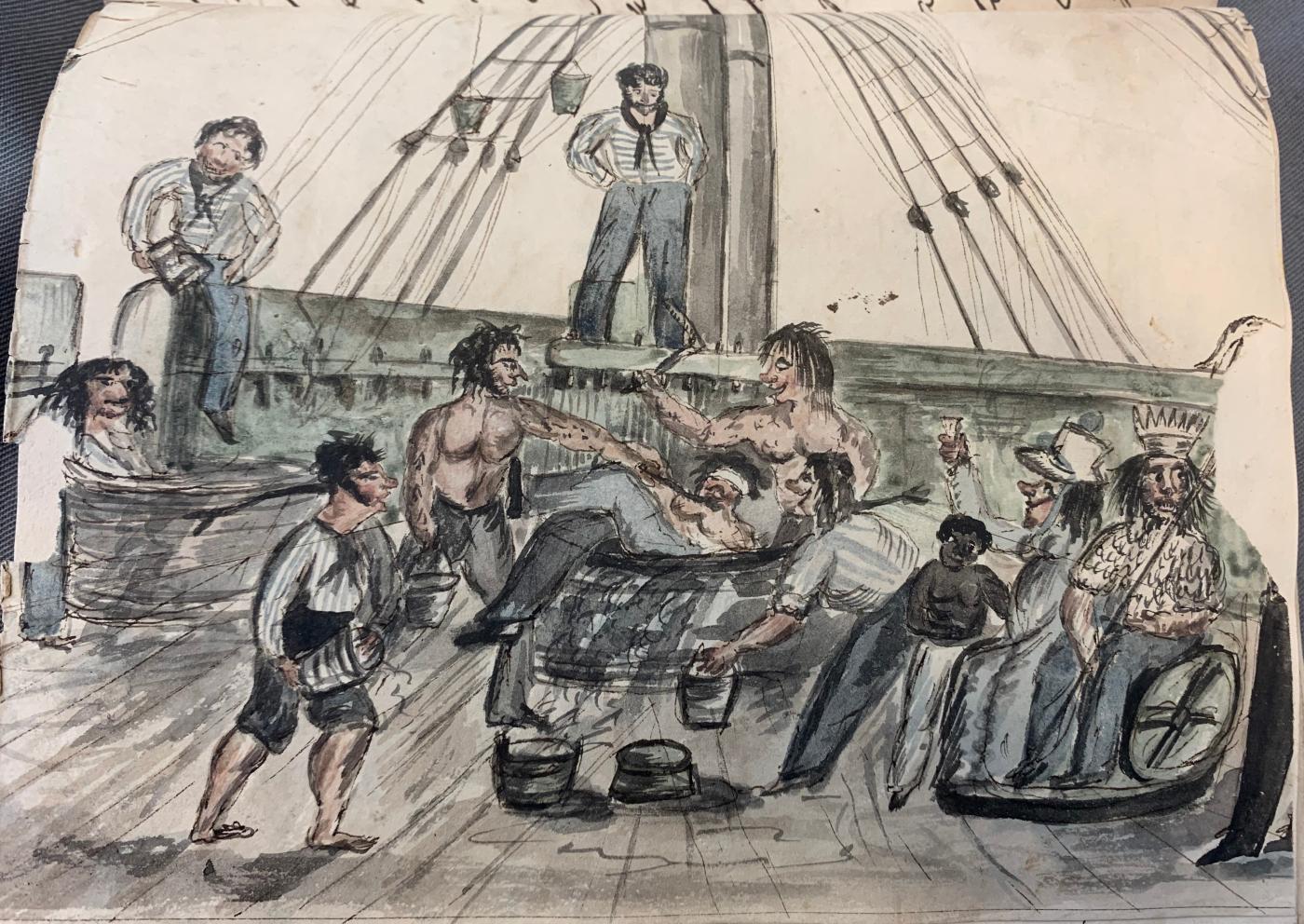

Freeboy is furious about being informed upon and, suspecting Strong, challenges him with 'his bunch of fives'. The fracas is captured by Gardner, who sketches Freeboy on the deck having received a 'back hander on his tender proboscis' from Strong in return.

The antics on board continue when another incident of 'a trifling nature very near turned out a tragical catastrophe'. After a perceived slight, Gardner's wife challenges another passenger, Josiah Smith (who had joined the 'Hotspur' at the Cape) to a duel. Smith, thinking 'that it was such a novelty to receive a challenge from a lady' decides to accept the challenge.

They assemble on deck, measure off twelve paces, and Mrs Gardner fires a shot at Smith. It misses when he ducks and hits Strong instead, who 'had placed himself on one of the sham sofas on deck, and not for a moment anticipating such a salute'.

Smith, it transpires some time later, was not Mr Smith at all. By his own admission, he changed his name from Snelgrove to avoid association with a brother who had committed 'something bad!'. Unsurprisingly, many of the characters Gardner comes across on his arrival in Sydney turn out to have shady pasts.

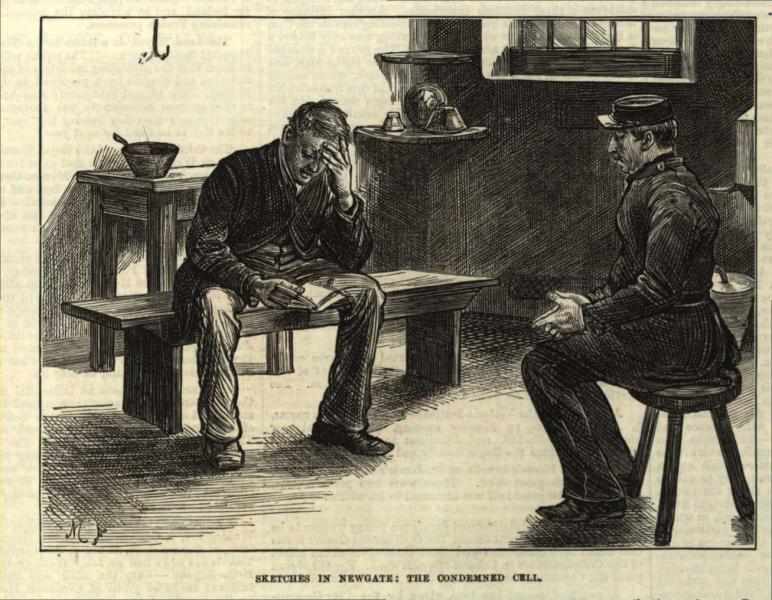

There is the 'Iron Gang' - heavily manacled convicts "of the worst class" charged with repairing the roads, the runaway convicts Patrick O'Donohue and Dennis MacNamara with £200 on their heads and Mrs Walker, a 'wall-eyed old lady' who had been sent to the colony 'for borrowing a cob from a relation which she entirely forgot to return to her'.

Then there is Lucy Charrington, transported for fourteen years for stealing a silver knife from her aunt, whose tragic death culminated in Gardner's own judicial inquiry. Lucy was to become Gardner's servant, but she was killed when the horse and gig in which she and Gardner were travelling overturned on the road.

An untimely end

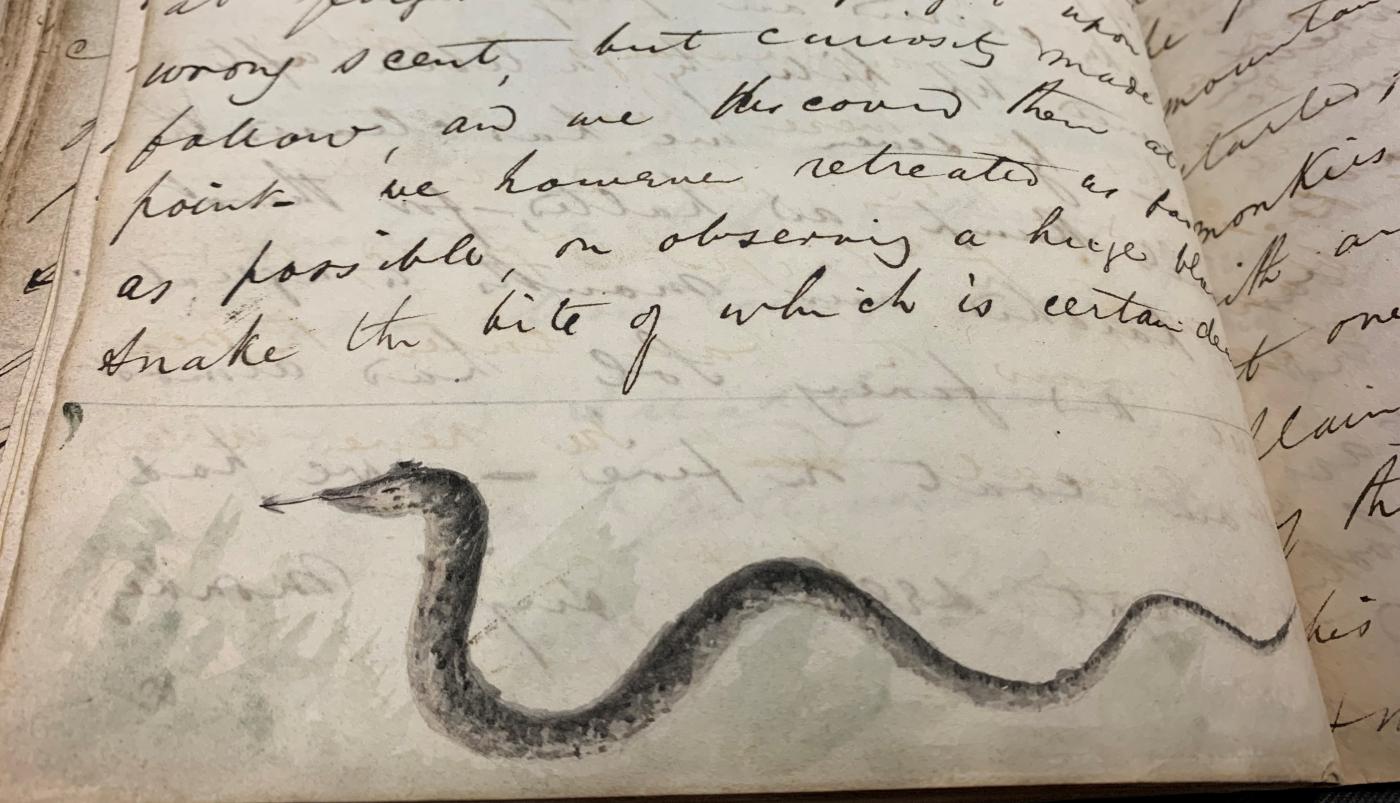

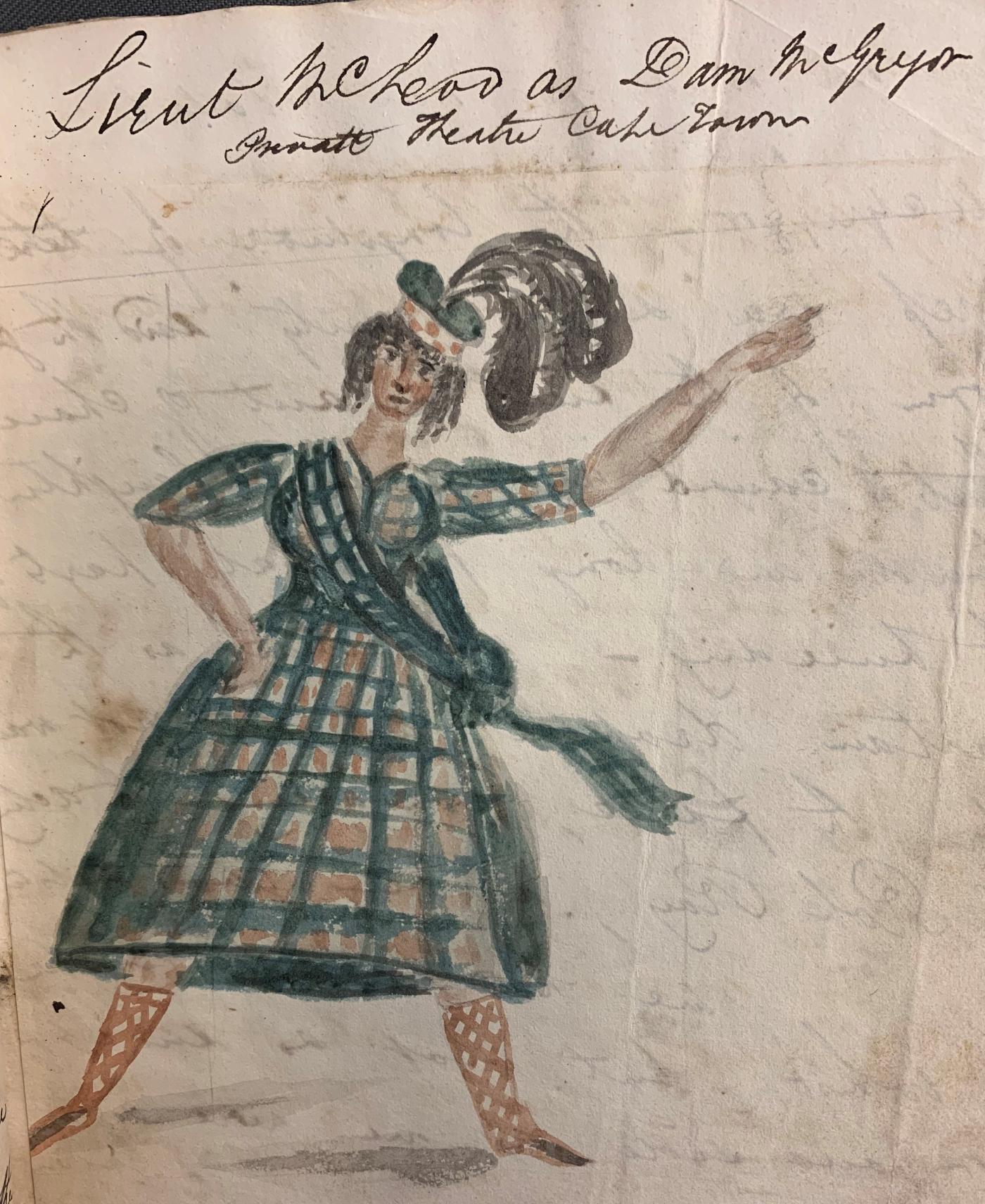

Gardner's journal comes to an abrupt end, frustratingly, after his acquittal, and the reader is left to speculate as to how the rest of his adventures in Sydney play out. Albeit truncated, his journal has handed down to us a colourful cast of characters and comical descriptions of life on board: the agony of being seasick, a farcical crossing-the-line ceremony, Josiah Smith drunkenly begging for tea, his encounters with venomous snakes, wild boars, orangutans and raging monkeys, a theatre production of Rob Roy by the 72nd Highland Regiment stationed at Cape Town – in which a Lieutenant McLeod plays Helen MacGregor, the experience of eating cape pigeons and the very real prospect of entirely depleting their provisions of food and water (and linen) before arriving at their destination.

Gardner did return to England, although we don't know when. His wife Isabella died and in 1843 he married Louisa Emily Bolton, the daughter of Samuel Bolton, Captain 23rd Fusiliers. Gardner became an army captain himself, in the 3rd Regiment of Foot, later known as the Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment). He died in 1889, aged 84, in Bushey, Hertfordshire.

Further reading

Recollections of James Anthony Gardner Commander R.N. (1775-1814), Hamilton, Sir R Vesey, Knox Laughton, John, Eds, Navy Records Society, 1906