Caroline Herschel (1750-1848) was a German-born astronomer who battled against prejudice to become an accomplished and respected member of the astronomical community.

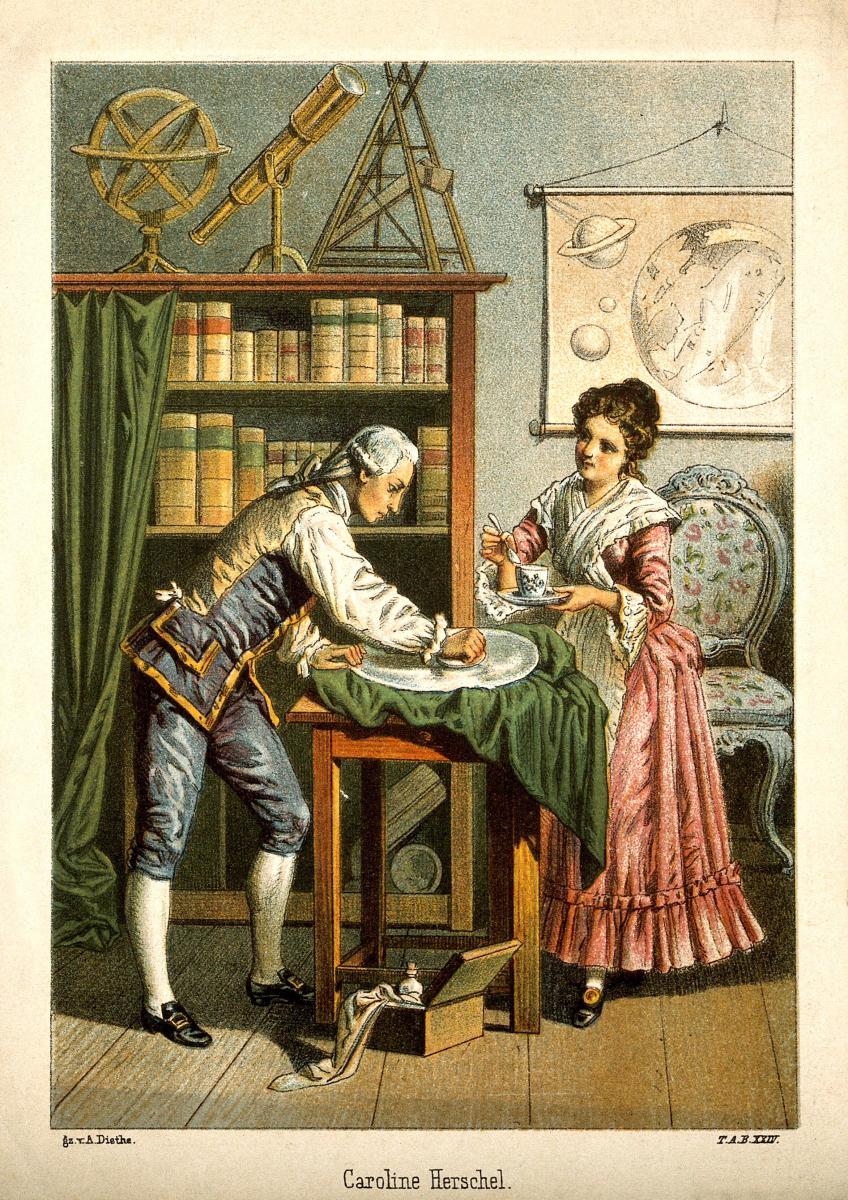

She did important work assisting her brother Sir William Herschel, a groundbreaking astronomer who discovered Uranus amongst other achievements.

However Caroline also did revolutionary work of her own, including becoming the first woman to discover a comet, revising John Flamsteed’s star catalogue, and cataloguing over 2,500 nebulae.

Throughout her life Caroline forged a path for herself in a male-dominated field, leaving a lifetime of domestic work in Germany to join her brother in England and work alongside him in music and astronomy.

Discover Caroline Herschel’s story with the Royal Observatory Greenwich.

Caroline’s upbringing and entry into astronomy

Caroline Lucretia Herschel was born in Hannover in 1750.

She spent her youth doing chores for her demanding mother, who believed her daughters should not do anything other than help run the household.

In 1766 her brother William (pictured) became an organist in Bath and so in 1772, at the age of 22, Caroline went against the wishes of her mother and crossed the Channel too.

She was trained as a singer by her brother and only six years later sang as a premier soloist in his concerts in Bath.

However, their musical life changed dramatically when William's obsession with his new hobby – astronomy – took over. He dedicated himself to studying, and tutored Caroline in English and Mathematics.

Naturally, Caroline began helping William more and more with his astronomical interests.

It was after William's remarkable discovery of Uranus in 1781, the first planet to be discovered using a telescope, that he gave up music and the siblings moved near Windsor to act as astronomers to the Royal Family under the patronage of King George III.

Caroline’s astronomical work

Assisting William included grinding and polishing mirrors, making calculations using his observations, and taking care of domestic matters.

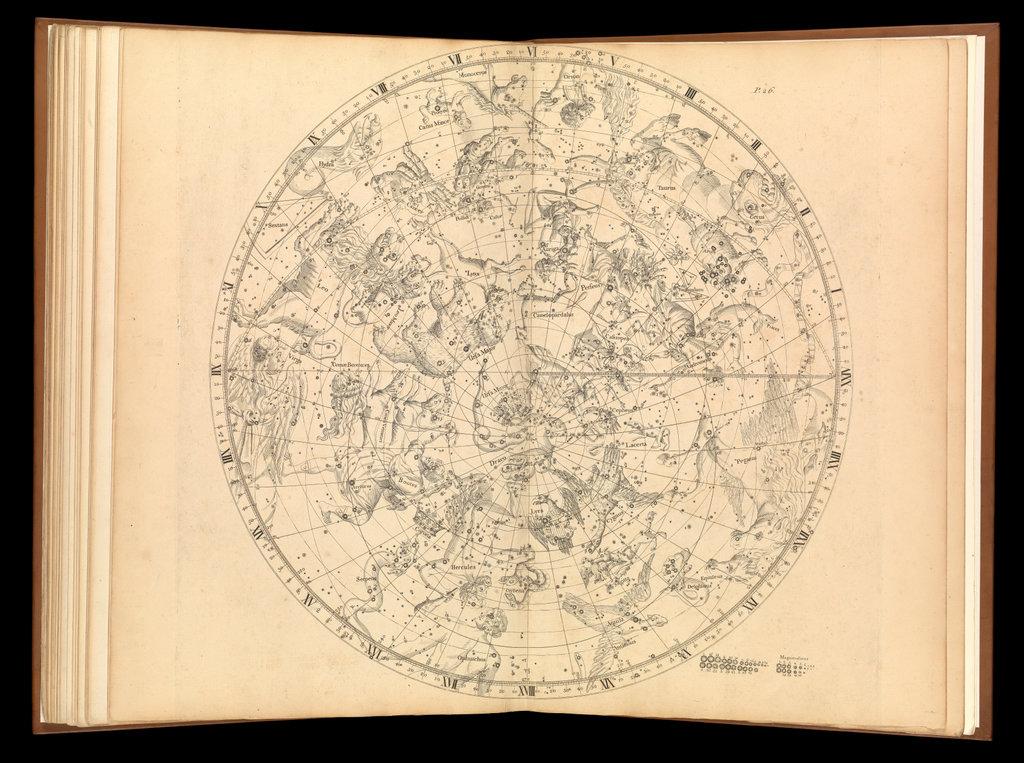

Using a telescope specifically made for her by William, Caroline began sweeping the skies looking for comets. By 1783 she had detected three new nebulae (gas clouds) and three years later she became the first woman to discover a comet, now known as Comet C/1786 P1 (Herschel).

She discovered eight comets in total, the final one in 1797. When she spotted it she rode nearly 30 miles to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich to tell the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne.

Having made herself recognisable as an astronomer in her own right, in 1787 King George III granted Caroline a £50 salary as William's assistant. This made her the first female in Britain to earn an income for the pursuit of science as well as the first woman to earn a living from astronomy.

When William married Mary Pitt in 1788, Caroline relinquished much of her household work to his wife, meaning she had more time to dedicate to astronomy.

She completed a mundane but essential task: checking, calculating, correcting and updating the Historia Coelestis Britannica, a catalogue of nearly 3,000 stars that had been compiled over 60 years earlier by the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed. It took Caroline a gruelling 20 months to complete the task.

In 1798 she published her work via the Royal Society, improving Flamsteed’s catalogue with an index of 500 extra stars and multiple corrections.

Following this, Caroline spent a week in Greenwich in 1799 as a guest of Nevil Maskelyne, who referred to her as ‘my worthy sister in astronomy’.

Life after William – Caroline Herschel's later life

Following William’s death in 1822, Caroline returned to Hanover, where she continued cataloguing nebulae and star clusters.

As well as her own work she began to help William’s son John Herschel, who had taken up the family mantle by going into astronomy.

On completion of her catalogue of 2,500 nebulae, Caroline was awarded a gold medal from the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828. Then, in 1835, she was one of the first two women to be accepted as an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society, the other being Mary Somerville.

Caroline Herschel died in 1848 at the age of 97. She was highly regarded by the astronomical community across Europe and today remains an inspirational figure within the field.

During her lifetime she received many accolades for her discoveries, including a Gold Medal and Honorary Membership of the Royal Astronomical Society, Honorary Membership of the Royal Irish Academy, and the Gold Medal of Science from the King of Prussia.

Caroline wrote the inscription for her tombstone herself. It reads, "The eyes of her who is glorified here below turned to the starry heavens."

Caroline Herschel’s legacy

Today, a number of astronomical objects still bear her name, including an asteroid named ‘Lucretia’, a lunar crater titled ‘C.Herschel’, and the star cluster ‘Caroline’s Cluster’ (NGC 2360).

Image: Satellite Cluster around 47 Tucan by Alice Fock Hang, Astronomy Photographer of the Year