In May 1672, off the coast of Southwold Bay in Suffolk, a Dutch artist by the name of Willem van de Velde the Elder took up position in a small boat.

He was about to bear witness to carnage.

Surrounding him were hundreds of warships. A Dutch fleet had sailed to engage a combined force of English and French ships, and Van de Velde was there to document the action.

The engagement became known as the Battle of Solebay. While both sides claimed victory, the outcome remained inconclusive.

The drawings Van de Velde made however would go on to shape how the battle was perceived, and eventually inspire a series of giant tapestries depicting the course of the conflict.

One of these tapestries is now in the collections of Royal Museums Greenwich.

Titled The Burning of the Royal James at the Battle of Solebay, 28 May 1672, the tapestry depicts the climax of the battle: the destruction of the English flagship Royal James and the death of vice-Admiral Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich.

Much like the outcome of the battle, the tapestry’s history is ambiguous. Following extensive conservation work, the tapestry is on display in the Queen's House.

Discover the story of this extraordinary work.

Ships, sea and royalty: the politics of the Solebay tapestry

During the 17th century, England underwent tremendous social and political upheaval. This was a time that witnessed the English Civil War (1642-1651), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the exile of Charles II and his restoration to the throne in 1660.

Against this turbulent backdrop, Charles II commissioned a series of six tapestries, designed to record the Battle of Solebay and celebrate the English Navy.

This was an unusual commission in more ways than one.

For a start, most tapestries of the period depicted classical or mythological scenes. To portray a naval battle in this form therefore was a political as well as creative choice.

For Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York (later James II), the Battle of Solebay was one of the Stuarts’ most important naval engagements. James was Lord High Admiral of the Fleet, in charge of the group of combined English and French ships.

“The Stuarts saw the Battle of Solebay as their own Armada,” explains Dr Imogen Tedbury, Curator of Art (pre-1800).

Maya Wassell Smith, Principal Researcher for the Solebay tapestry research project, adds that the tapestry commission was part of a wider strategy by the Stuarts to re-establish their royal authority.

“By commissioning the tapestries, the Stuarts were building back their Royal Collection – which was largely requisitioned during the interregnum – to assert their claim to the throne,” she says. “As the Battle of Solebay didn’t have a clear victor, the tapestries are a form of propaganda, which the Stuarts used to showcase their naval success.”

Dutch artists, English spin: the van de Veldes and the Solebay tapestry

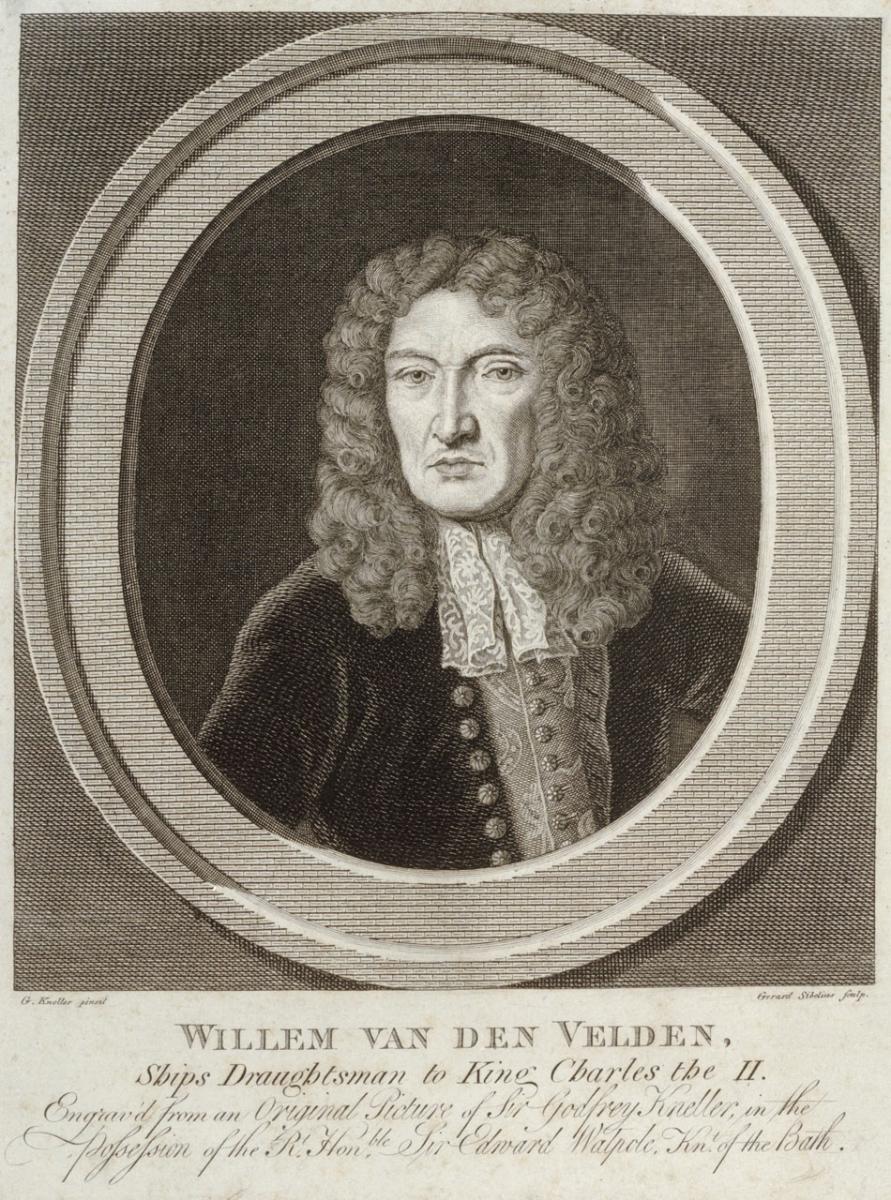

To bring the tapestry series together, Charles II enlisted the artistic talents of Willem van de Velde the Elder.

In the winter of 1672/1673, Van de Velde and his son Willem van de Velde the Younger moved to England to take up Charles II’s offer of a studio at the Queen’s House in Greenwich.

Van de Velde the Elder was an established marine artist, known for his detailed drawings of ships and battles.

“He was a proto photojournalist,” explains Sue Prichard, Research Associate at Royal Museums Greenwich. “He was at the site of battles, sketching and recording events, and would work up the sketches into paintings back on land.”

Van de Velde had been an eyewitness at the Battle of Solebay, and therefore seemed ideally placed to fulfil this royal commission. There was just one problem: when he had been at Solebay, he was there on the side of the Dutch, not the English.

“When Van de Velde is commissioned to make the drawings for the tapestries, he’s asked to reimagine the scenes from the point of view of the English,” explains Tedbury. “Van de Velde adapted the studies that he had made, and used that information to create the cartoons for the tapestries.”

The Solebay story

Sign up to the art newsletter for more information about the Solebay tapestry, and find out more about exhibitions and events at the Queen's House.

From sketch to stitch: creating the Solebay tapestry

To create the tapestry series, Van de Velde used his drawings to create 'cartoons' – large-scale paper designs – that would act as a guide for the skilled weavers employed to produce the final piece. The cartoons were laid out on the first floor of the Queen’s House before being sent to the tapestry workshop.

While the original cartoons are now lost, it was initially thought that they were taken to the Mortlake tapestry manufactory. Located near Richmond in Surrey, the Mortlake workshop was established in 1619, with the royal patronage of James I. During the first half of the 17th century, it became the leading workshop for English tapestries.

“Tapestries would have been a very important status symbol during this period,” Wassell Smith says. “They were fantastically expensive and very labour-intensive, taking hundreds of hours to produce.”

However, parliamentary legislation introduced in the 1660s indicates that the Solebay tapestries may have actually been woven elsewhere. In 1663, an Act of Parliament withdrew the monopoly on producing tapestry at Mortlake, and so competition began to emerge from private workshops in central London.

“The Mortlake tapestry workshop started to go into decline,” Prichard says. “At the same time, the area around Covent Garden was starting to be regenerated following the Great Fire of London.”

The weaving of the Solebay tapestries is now thought to have taken place either at Clerkenwell or later at Hatton Garden in the workshops of Francis Poyntz. A skilled weaver, Poyntz was a Yeoman Arrarsworker in the Great Wardrobe, a position that involved producing new royal tapestry commissions as well as maintaining the existing tapestries in royal residences and collections.

“Francis Poyntz relied on skilled émigré weavers, many of whom were Catholic and had left the Dutch Commonwealth because of religious and economic turmoil,” Wassell Smith explains.

Despite the high anti-Catholic sentiment in England at this time, Poyntz campaigned to protect the rights of his Catholic workers: “In 1679, Poyntz petitioned the English crown to exempt his weavers from anti-Catholic laws, which excluded Catholics from political life as well as trade,” Wassell Smith says.

At Poyntz’s workshop, the weavers would have worked with Van de Velde’s cartoons, using their own skills to interpret his designs.

The Solebay series is severed

Francis Poyntz died in 1684, with only three of the six tapestries complete. There is a suggestion that the production encountered a funding shortfall during this period.

The final three tapestries – which include the tapestry in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection – were eventually woven under the direction of Francis’s relative Thomas Poyntz.

The story of the tapestries following their production is fraught with uncertainty. While the first three tapestries were retained in the Royal Collection, eventually ending up at Hampton Court Palace, the movements of the final three tapestries are less clear.

In 1695, an audit of the Royal Collection was made following the death of Mary II. Only three tapestries of the six tapestries are listed.

We do know that in around 1714, the final three tapestries were acquired by Lord Horatio Walpole, MP and ambassador to the Netherlands and France, and the brother of Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s first Prime Minister.

During this time, the Walpole coat of arms was added to the 'cartouches' at the top and bottom of Royal Museums Greenwich’s Solebay tapestry. This addition took pride of place in the middle of the elaborate border of the tapestry.

For the next 100-plus years, details of the final three tapestries are scant. However, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the tapestries are thought to have become part of the collection of Lord Iveagh at Pyrford Court.

In 1968, the tapestry in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection was bequeathed to the National Maritime Museum. The other two tapestries were acquired by Hampton Court Palace.

A closer look at the Solebay tapestry

Unlike the other tapestries in the series, which depict scenes of ships lining up for battle, the Solebay tapestry in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection captures a climactic moment of the conflict: the destruction of the Royal James, the Earl of Sandwich’s flagship.

This incident resulted in the loss of the Earl of Sandwich’s life. For Prichard, the drowning people depicted in the tapestry reinforce the human cost of war.

“It takes this macro view of the battle down to the micro, and you’re suddenly faced with very personal tragedy. You realise it’s a matter of life and death for these little figures,” she says.

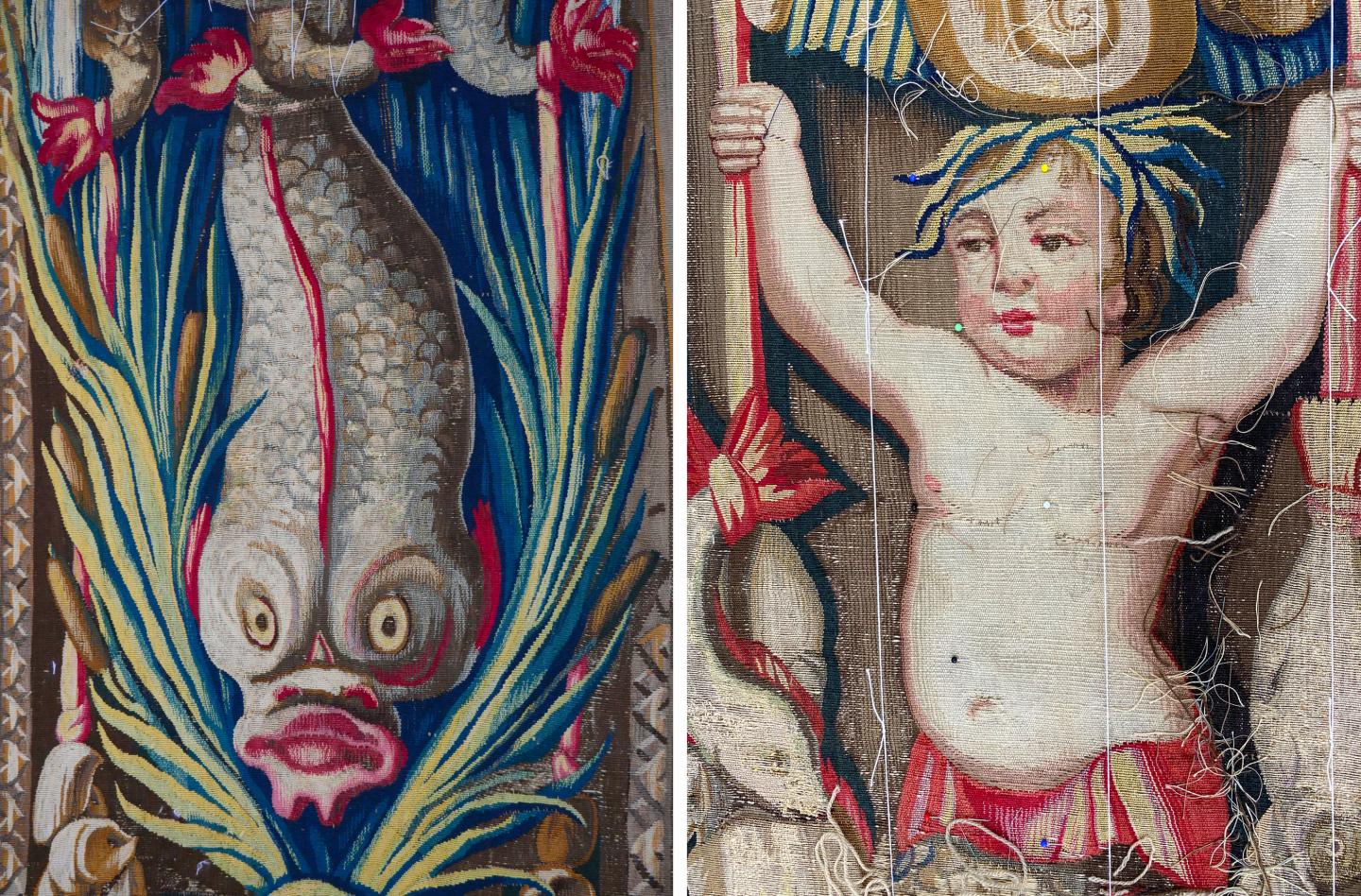

The tapestry in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection is framed by elaborate borders, filled with tritons, mermaids, lobsters and other mythical sea creatures.

“These are traditional motifs that you would see in tapestry borders,” Prichard explains.

One of Prichard’s areas of research is to compare the borders of the first set of six Solebay tapestries with the borders of a second set of tapestries, commissioned in 1688 by James, Duke of York (later James II) for the Duke of Dartmouth.

While the later tapestry series depicts the same scenes as the first series, the borders are markedly different.

“The borders in the second set are armorial, and feature cannons and maritime instruments,” Prichard says. “James was Lord High Admiral and a participant in the battle of Solebay, and the Duke of Dartmouth was also present, as captain of the Fairfax.”

The Solebay story continues

Today, the Solebay tapestries are the only surviving English naval tapestry series.

As part of a major research project, curators at Royal Museums Greenwich are piecing together the history of Greenwich’s Solebay tapestry. Research areas include trying to understand the creative exchange between Van de Velde, his royal patrons and the tapestry weavers, and tracking the movements of the tapestry over the last 350 years.

The team are keen to analyse the details in the other Solebay tapestries, in order to determine where Royal Museums Greenwich’s tapestry sits in the series.

More than 300 years after it was created, the tapestry, and the many threads of its story, are now being woven closer together.