The craft of tapestry weaving has long been associated with splendour, status and skilled craftsmanship.

Between the 14th and 18th centuries, the art form flourished across Europe. Elaborate tapestries adorned the walls of royal residences, stately homes and public spaces, often produced at considerable expense.

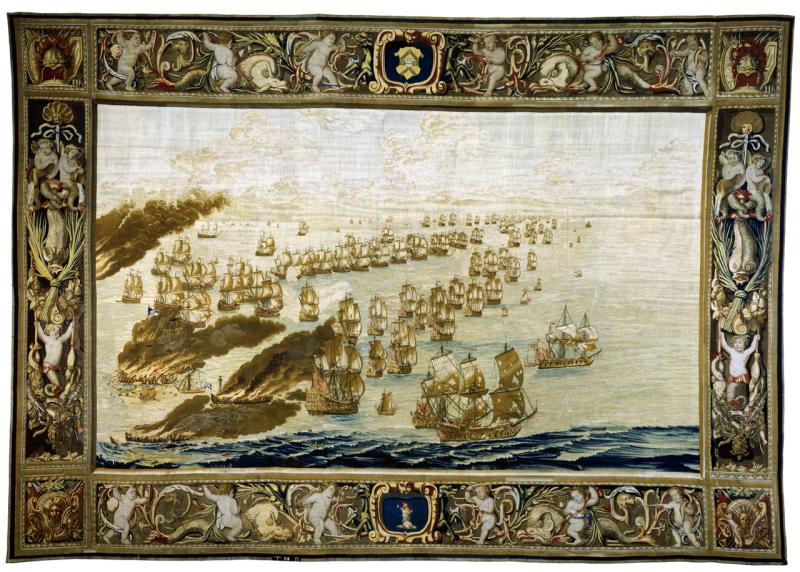

One such tapestry is in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection. Commissioned by King Charles II, the Solebay tapestry depicts the climactic events of a naval battle between Dutch ships and a combined English and French fleet.

Thanks to the overwhelming response to our crowdfunding campaign, the Solebay tapestry has been saved for future generations. Following extensive conservation work, it is now on display at the Queen's House.

How are tapestries made, and why are these cherished works so fragile? We ask conservators and contemporary weavers to share the secrets of this prized art form.

Creating a tapestry

A tapestry is a woven structure that has threads running in both directions.

Despite modern technological advances, the techniques involved in tapestry weaving have changed very little over time. Weaving a tapestry remains a labour-intensive process, requiring exceptional attention to detail.

Tapestries are made up of two types of threads: the warp and the weft.

To create a tapestry, the warp threads are first stretched out on a loom – a process that can take up to three weeks. The warp provides the structure of the tapestry. On a historic tapestry like the Solebay tapestry and other tapestries from the 17th century, the warp would have been made from wool: a strong and flexible material.

Into the warp is woven the weft: the coloured threads that make up the design of the tapestry. In historic tapestries, the weft would often have been woven from wool, silk and even gold threads.

Unlike the warp threads, which run all the way across the tapestry, the weft threads are discontinuous, in order to incorporate different colours and designs.

“If you were to compare the warp and weft threads in a tapestry with your jeans, you would see that the warp and weft in the denim run right across the fabric in both directions,” says textile conservator Zenzie Tinker.

It is this discontinuous structure that makes historic tapestries so fragile. “On historic tapestries, the weight of the tapestry hangs on the discontinuous weft, which is the weakest part of the structure,” Tinker explains.

As well as being more than 300 years old, the Solebay tapestry has a large amount of silk in its weft, a fibre that degrades more quickly than wool.

“The Solebay tapestry has a vast expanse of silk in the sea and sky, which makes the structure weak and vulnerable,” Tinker says.

These factors combined makes its conservation all the more pressing.

The cartoons: a tapestry template

Just like the Solebay tapestry’s original weavers, contemporary weavers work from a cartoon to bring a tapestry together.

A cartoon is a large-scale paper design that sits behind the warp threads. “It’s essentially a guide for the weaver,” says Philip Sanderson, studio leader at West Dean Tapestry Studio.

One of the only professional tapestry studios in the UK, West Dean Tapestry Studio works with contemporary artists and designers to translate their artworks into woven tapestries.

When working on a new commission, Sanderson and his team create a cartoon of the artwork, effectively turning it into a line drawing. This involves breaking down the design into a series of shapes, denoting colours and brush marks.

“All these details are really important for the weaver, so they can translate it into the weaving,” he explains.

Weavers at work

To begin with, the weaving process is very slow.

“The weavers have to get used to the image and working on the loom,” Sanderson says. “We go through a process called setting the tone of the piece, where we’re looking not just at the weaving we’re working on but at the whole image – the lightest and darkest areas – to make sure the tone is correct.”

As they work, the weavers refer to the original artwork, the cartoon and the palette of yarns to bring their sections of tapestry together. They must also coordinate their movements carefully with each other.

“We often talk about choreography,” Sanderson explains. “Even though you might have several people working on the loom, the tapestry needs to look like it’s been woven by one person. Communication is very important.”

The Solebay story

Sign up to the art newsletter for more information about the Solebay tapestry, and find out more about exhibitions and events at the Queen's House.

A prized art form

Because of the skill and time involved in the creation of a tapestry, the art form has long been associated with splendour and status. At the time of the Solebay tapestry’s creation in the 17th century, only the wealthy would have been able to afford a tapestry.

“Tapestries would have been a very important status symbol during this period,” explains Maya Wassell Smith, Principal Researcher for the Solebay tapestry research project. “They were fantastically expensive and very labour-intensive, taking hundreds of hours to produce.”

She adds that tapestries would also have served a practical function: “Tapestries would have been used as draft excluders, to create warmth and to absorb sound.”

Tapestry weaving today

In recent years, there has been a resurgence in tapestry weaving. Since 1976, West Dean has worked with pioneering artists, including Henry Moore, Tracey Emin and Eva Rothschild, to translate their artworks into woven tapestry.

“There are a lot of artists who are engaging with tapestry, and who are contacting us to have tapestries made for exhibition,” Sanderson says. “Weaving is a vibrant area.”