The English language is peppered with phrases we don't really think twice about, but which are slightly peculiar on reflection.

Why do we say 'there isn't enough room to swing a cat' if we're in a small space, or call someone a 'loose cannon' when they're a bit unpredictable? Why do we 'wipe the slate clean' when making a fresh start or call someone 'three sheets to the wind' when they're drunk?

The answer lies in our seafaring past.

Track down the maritime origins of popular phrases with the National Maritime Museum, and explore how their definitions have shifted across the years.

A copper-bottomed newsletter

Join the crew and sign up for news, events and stories from Royal Museums Greenwich, the home of Cutty Sark and the National Maritime Museum.

Loose cannon: If a cannon on board a ship broke free from its securing ropes, it would pose a danger to both the ship and its crew. Nowadays we might describe someone as a 'loose cannon' if they are known to be dangerous and unpredictable.

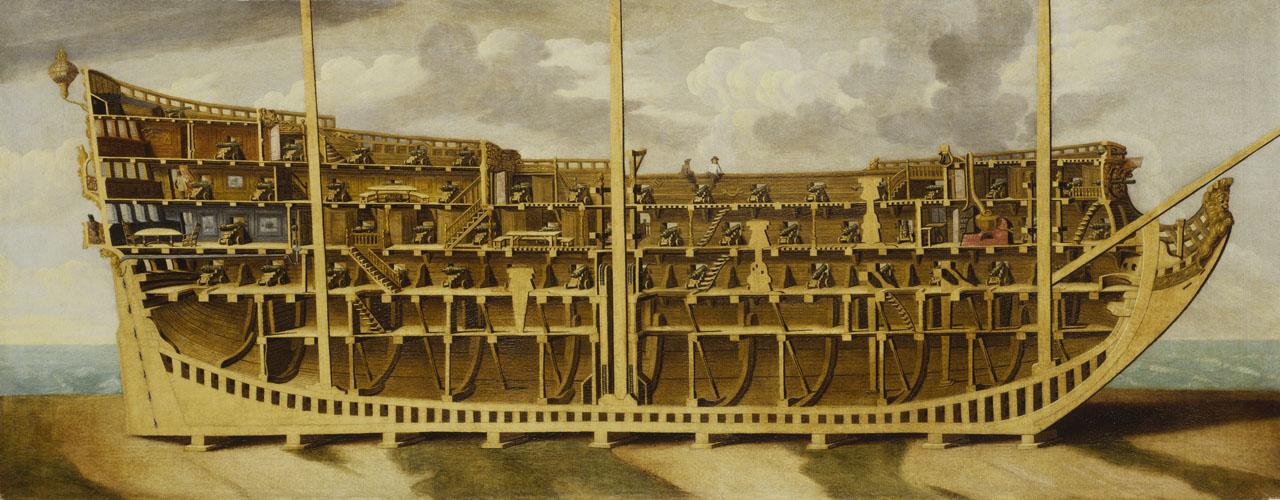

Son of a gun: Rumour has it that a 'son of a gun' was a baby born on board a ship, perhaps between the guns of a gun deck. Now 'son of a gun' is an insult; on rarer occasions you may even hear someone exclaim it in surprise!

Flake out: This phrase comes from when a crew would 'flake out' an anchor chain (lay it out flat) on the deck to check the chain links for signs of wear. Today, to 'flake out' is to be completely worn out or fall asleep.

As the crow flies: If you travel 'as the crow flies' then you travel in a straight line, avoiding any obstacles. One theory for the origin of this phrase is that Vikings released land-loving crows or ravens from a ship to help find a route to the nearest shore. Legend has it that this is also why the lookout point at the top of a ship was called the ‘crow’s nest’, named after the place where Viking sailors kept their crows or ravens in a cage.

Chock-a-block: ‘Blocks’ (pictured on Cutty Sark) are part of a ship’s pulley system. When the rope linking two blocks pulls them tightly together, it prevents any further movement in the rigging.

Today you may hear this phrase referring to traffic or very crowded places, where it means full to the point where nothing can move.

To have things ‘all sewn up’: When a sailor died on board, they would be sewn into their hammock or a canvas sailcloth. They would then be weighted down before being buried at sea. Now the phrase has a slightly less morbid meaning: if you have things 'all sewn up', it means you’ve completely finished doing something.

‘I like the cut of your jib’: Jibs are triangular sails that are found at the front of a ship. The shape of jibs varied across countries and nations, and as a result, 18th-century sailors could identify a warship as a friend or foe by the shape of their jib. Nowadays, if you like the cut of someone's jib then you like the way they look or act.

Cut and run: If a ship needs to make a quick getaway in the face of danger, there may not be enough time to raise the anchor. To prevent damage to the ship therefore, a crew might decide simply to 'cut' the anchor free and 'run' for safety. 'Cut and run' today usually means to cut your losses and get out of a situation or leave very suddenly – even if you have to leave something behind.

‘At a rate of knots’: Knots are a measure of speed. They’re still used today, and not only at sea: for example, on an aircraft a pilot might talk about the predicted speed of the plane in knots.

The word ‘knots’ comes, quite literally, from knots in a rope. To measure speed at sea, sailors would use a log line (pictured). Knots were tied into a piece of rope at regular intervals. The rope was attached to a float, which was dropped overboard.

As the rope unwound from a reel, the number or 'rate of knots' that passed was counted to calculate the speed of the vessel. Today if you do something 'at a rate of knots', it means you are doing something very quickly.

The bitter end: The bitter end is the final part of an anchor chain or rope that secures the anchor to the ship. To reach the bitter end was to have the chain or rope extended as far as it can go. Similarly, if you say you've reached the 'bitter end' today, it means you've gone as far as you can, often in a difficult situation.

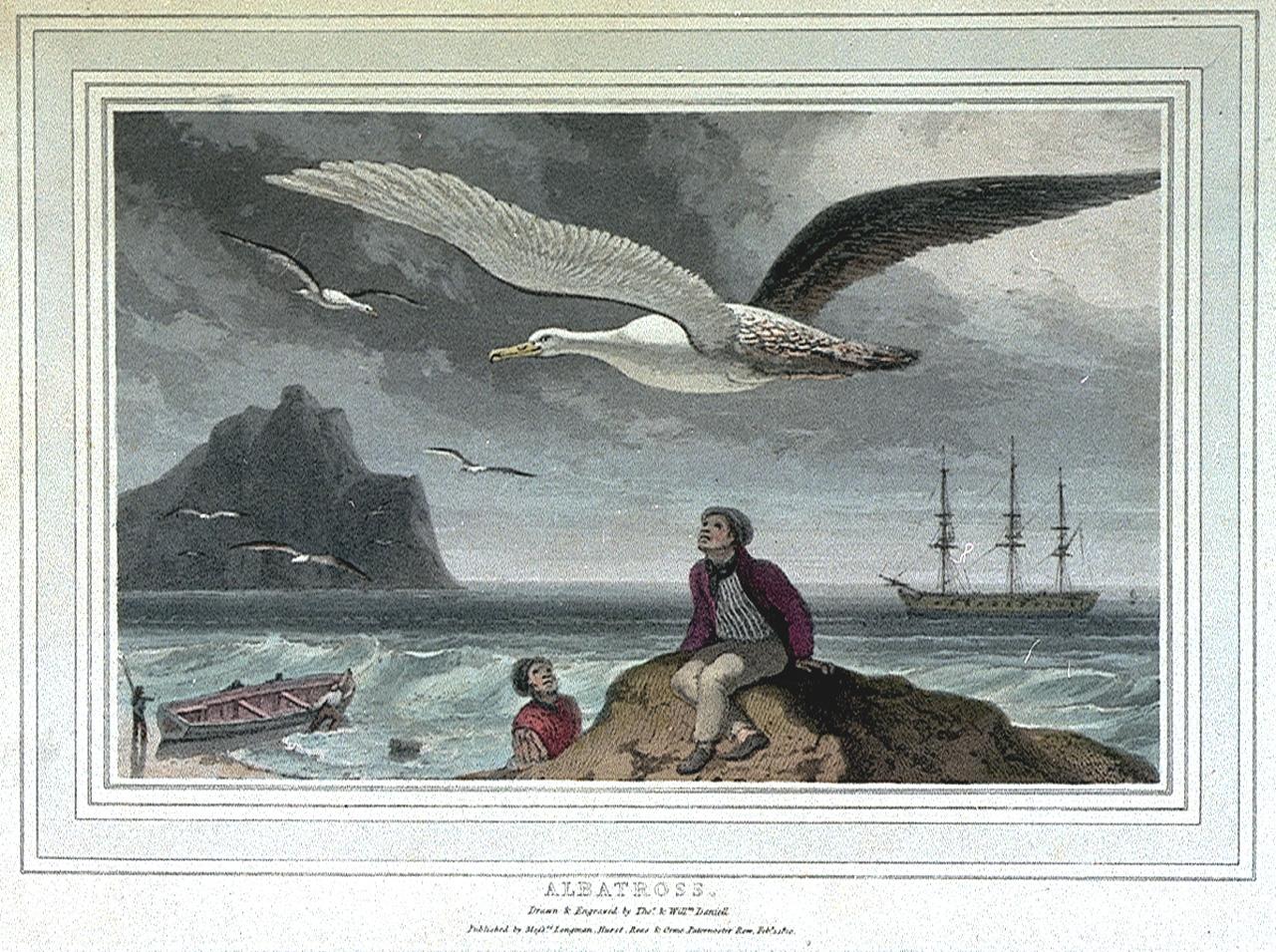

‘An albatross around your neck’: This phrase comes from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. In the poem an albatross, which is a sign of good luck, is killed by a sailor. He is then forced to carry the enormous bird around his neck as punishment. Nowadays we might say that someone has an albatross around their neck to mean that they carry a difficult or heavy burden.

‘A leading light’: When docking at night, lights on shore helped guide ships safely into port, and a ‘leading light’ was prominently positioned for this purpose. Today someone might be described as a 'leading light' if they are well respected in a particular field – particularly if they're someone that people follow for guidance.

'Not enough room to swing a cat': The word 'cat' within this phrase doesn't refer to a feline, but rather to a whip called the ‘cat-o'-nine-tails' (pictured).

A flogging with a cat-o'-nine-tails was an infamous naval punishment. However, it was usually too cramped to swing the whip below deck – hence this phrase was born. Today you might use this phrase to describe a small, confined space.

‘You’ll have the devil to pay’: Sailors had to caulk (or ‘pay’) the seams of the ship to keep them watertight. This involved stuffing the gap first with oakum (rope fibres) and then sealing it with hot tar.

This is one suggested origin for the phrase 'the devil to pay', where a particularly tricky seam to caulk would be referred to as the 'devil'. Today, you might hear someone say ‘you’ll have the devil to pay’ – to mean you’ll have a very difficult task to do.

‘Caught between the devil and the deep blue sea’: Rumour has it that to caulk the devil seam of the ship, a sailor had to hang off the side of the boat. Hence, they would be ‘caught between the devil and the deep blue sea’.

Copper-bottomed: This phrase dates back to when ships were fitted with metal sheets of copper or brass (like our very own Cutty Sark, pictured).

Metal sheathing stopped barnacles from attaching to the hull and slowing the ship down. It also protected the wooden frames underneath from wood-boring ship worm, which could cause a ship to sink. Today you might say that something reliable, sturdy or strong is 'copper-bottomed'.

‘Hit the deck’: Sailors might ‘hit the deck’ or dive to the floor if under attack. The meaning is pretty much the same today: if some ‘hits the deck’, it means they've fallen to the floor, intentionally or accidentally.

At a loose end?

Find more surprising tales of the sea and maritime history with Royal Museums Greenwich.

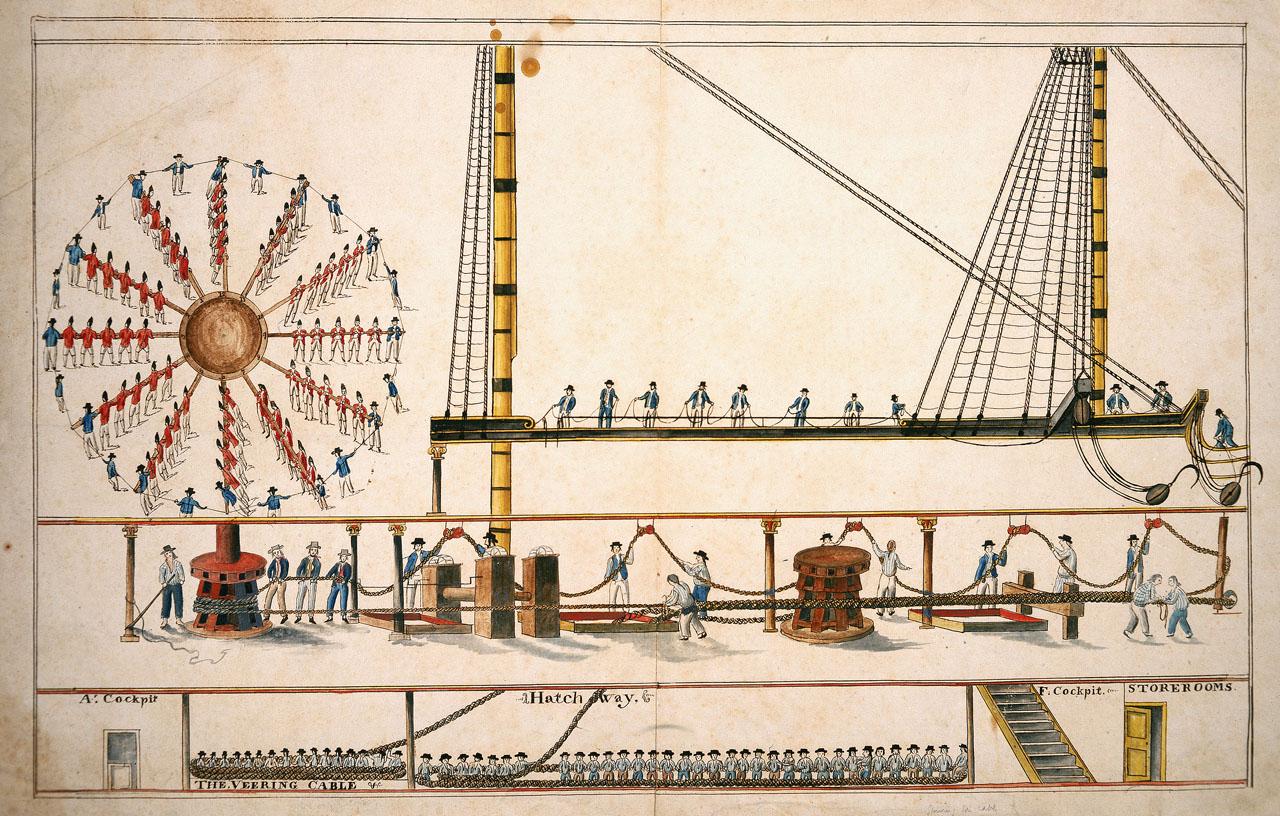

‘Anchors aweigh!’ When hoisting an anchor, someone might cry out ‘anchor's aweigh!’ (not 'away') when they start to feel the weight of the anchor as it breaks free from the seabed. While not heard as much nowadays, you might hear someone exclaim this to indicate something has begun.

‘On an even keel’: A keel is a ship's backbone, the long piece of wood or metal running along the bottom of the hull. If the keel is even then the ship is stable in the water. As a result, you might use this phrase to describe something as steady and predictable.

Groggy: This adjective comes from the word 'grog', which was the daily ration of watered-down rum for sailors. When sailors had a bit too much to drink, they would be referred to as groggy. Today you might be called groggy if you're a bit drunk, but it's mainly said when someone is still half asleep in the morning, ill or disorientated.

'Three sheets to the wind': On a sailing ship, if the three sails were loose and blowing about in the wind, the boat would lurch side-to-side like a drunken sailor. Nowadays, if someone is three sheets to the wind, they're usually fairly drunk.

Pipe down A boatswain or ‘bosun’ was a ship’s officer who was, amongst other duties, in charge of the crew. He would issue different orders to crew members by changing the sound patterns blown on his 'call', a sort of high-pitched whistle.

'Pipe down' was the last order of the day for off-duty crew to stop talking, settle down or go to bed. Today, the phrase 'pipe down' is still used to tell someone to be quiet.

‘Posh’: Posh is an acronym for ‘Port Out and Starboard Home'. Historically the best cabins for cruise ships travelling to and from India were on the port side on the way out, and on the starboard side on the way back. This was the shaded part of the ship, protected from the heat of the sun. In the days before air conditioning this was a crucial feature, and so therefore these cabins were reserved for richer passengers. Some think this acronym, POSH, is why rich or well-to-do people are known as 'posh'.

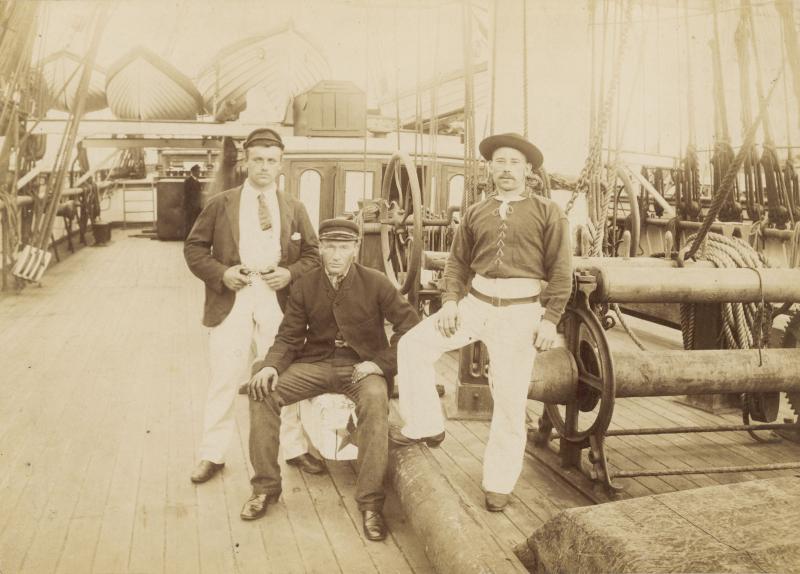

‘Show the ropes’ and ‘know the ropes’: Among the many essential skills for sailors, it was crucial to ‘know the ropes’ on board a ship – and there would be a lot of ropes to know.

For example, Admiral Lord Nelson’s HMS Victory required a staggering 26 miles of rigging. Knowing what each rope did and what it was connected to ensured a ship's smooth operation.

Today, you’re likely to be shown the ropes when starting a new job or hobby, and you 'know the ropes' once you have an informed understanding of how to do something.

‘Batten down the hatches’: When a storm was on its way and the sea was expected to be particularly rough, the captain would give the order to ‘batten down the hatches’.

Hatches were openings in the main deck, usually covered with wooden grating, designed to allow cargo into the hold and ventilate the ship's interior. To batten them down meant to cover them with tarpaulin, which was secured in place with wooden strips known as battens.

Today you might hear someone advise you to batten down the hatches to mean you should prepare for a big storm or some other trouble coming.

‘Down the hatch’: Cargo would be lowered down the hatches to reach the hold, almost as if the ship was 'eating' the goods – which is why you may hear someone say, ‘Down the hatch!’ to tell someone to eat or drink something.

‘Dead in the water’: On a windless, still day, a ship could sit motionless or ‘dead’ in the sea. 'Dead in the water' now refers to a project or an idea that has no momentum and is not going anywhere.

‘Plain sailing’: Sailing that is straightforward and easy is 'plain sailing'; today you might say something is 'all plain sailing' if it doesn't require much effort.

'Take the wind out of their sails': If a ship moves in front of another ship and blocks the wind, it could slow right down or stop completely. Nowadays, to take the wind out of someone's sails means to discourage or demotivate them from doing something.

‘At a loose end’: When sailors would run out of tasks on board, in order to prevent them from becoming idle the captain might have asked them to check the ends of ropes and make sure none of them had started to unravel. Nowadays, you might find yourself at a loose end if you’ve run out of things to do or are unsure of what to do next.

Hitched: At sea, when a sailor joined two ropes together they were said to be ‘hitched’. Now, this phrase colloquially means to get married.

‘Make ends meet’: Similar to hitching, when sailors would attach two pieces of rope to make one long piece they were said to be 'making ends meet'. Nowadays this means to make just about enough money to live on or get by.

‘A clean slate’: Deck slates, like the one pictured, would be used as deck logs to keep note of important navigational information like knots, fathoms (depth of the water) and wind speed.

At the end of the night shift when the calculations were no longer useful, the slate would be wiped clean by the new officer on watch.

Today, to 'wipe the slate clean' means to make a completely fresh start or let go of the past.

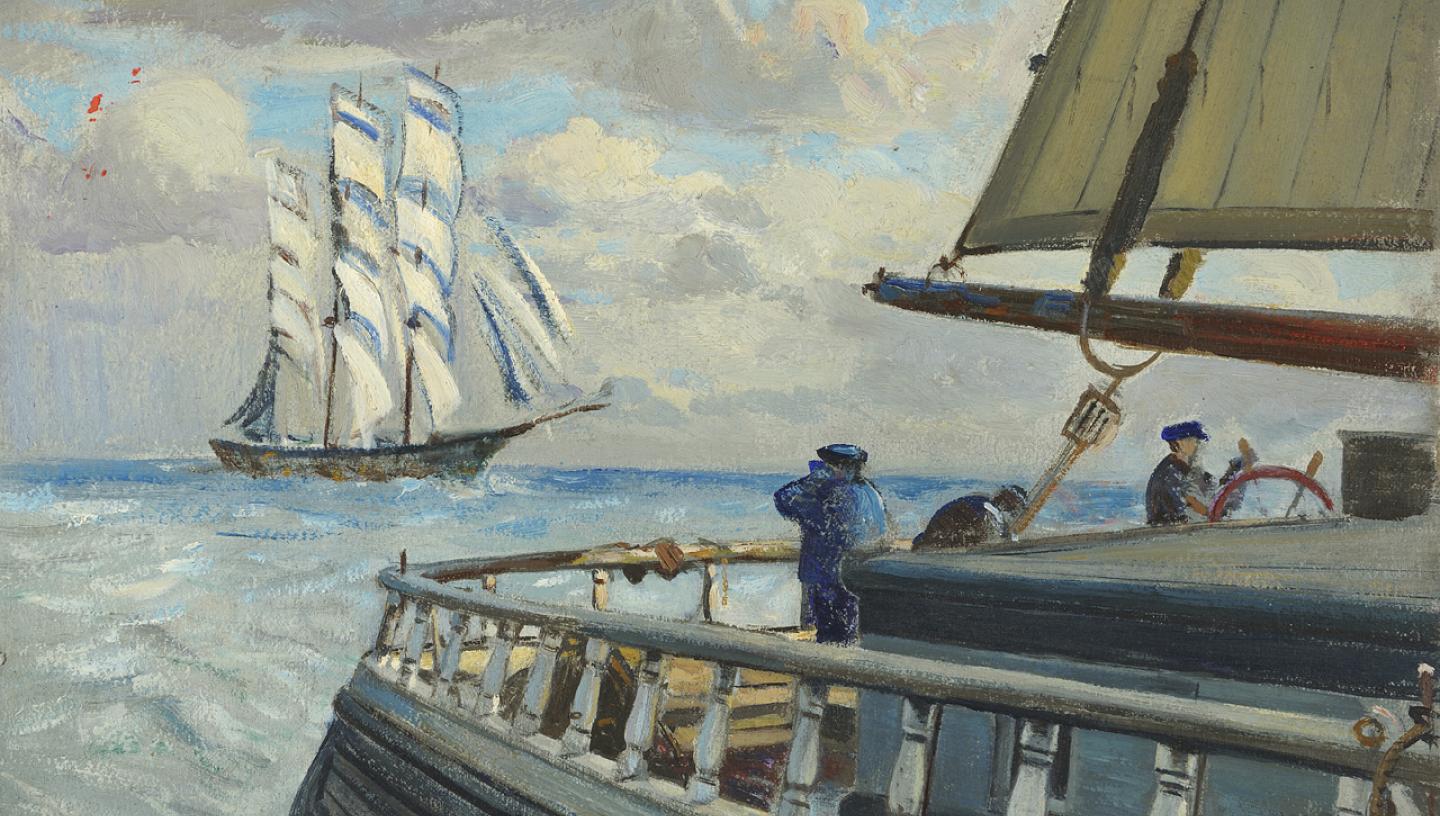

Header image: A sailing ship by John Everett (BHC4098), credits National Maritime Museum. All other images from the National Maritime Museum collections.