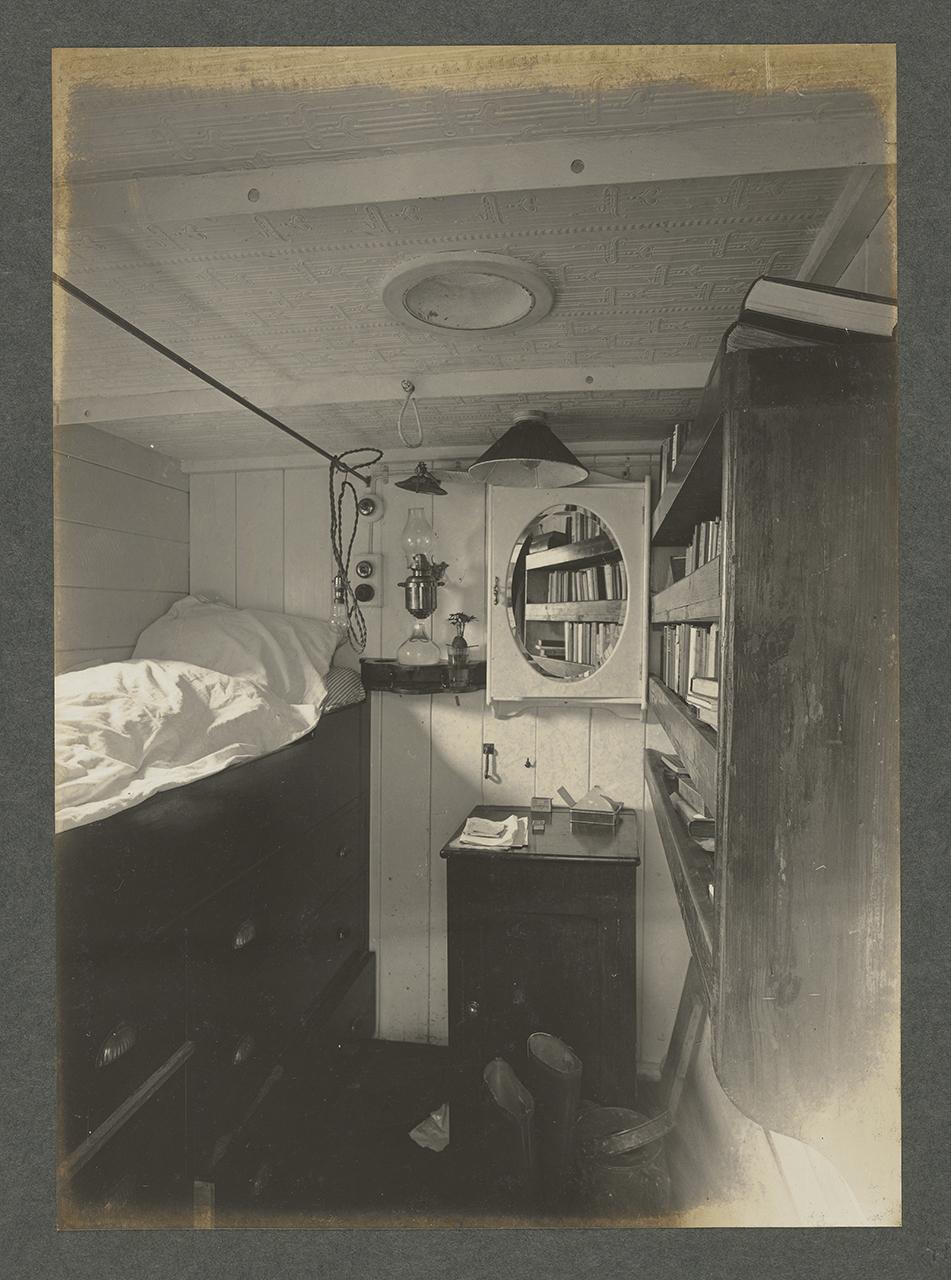

At around 2.50am on the morning of 5 January 1922, Sir Ernest Shackleton died in his cabin on board the exploration ship Quest, while it was anchored off South Georgia. He was 47 years old.

His death came as a great shock to the crew, some of whom had served with Shackleton on his Imperial Transantarctic Expedition on board the Endurance, 1914-1917.

Dr Alexander Macklin, who was on watch that evening, had visited Shackleton in his cabin and, after encouraging him to take things easy, was rebuked with the words:

…“You always want me to give up something. What do you want me to give up now?” This was the last thing he said. He died quite suddenly.

The whaler Professor Gruvel took Shackleton’s embalmed body from South Georgia to Monte Video, accompanied by Leonard Hussey. Here Hussey received a telegraph from Emily, Lady Shackleton, requesting that Shackleton’s body be buried on South Georgia.

Despite all that Shackleton had put Emily through during their marriage, she really understood the restless spirit of the man and his fascination with the Antarctic. Where better to let him rest than at the ‘Gateway to the Antarctic’, in the stormy Southern Ocean off Antarctica?

Shackleton's reputation

During his lifetime, Shackleton had a complicated reputation. Like many people driven to achieve particular goals, he created a complexity about his life that resists easy conclusions.

Many of those who served with him were very loyal, referring to him as ‘The Boss’ and joining him on more than one expedition.

For Frank Wild, who had served on many Antarctic expeditions with Shackleton as well as his contemporaries Captain Robert Falcon Scott and Douglas Mawson, his view was that Shackleton was 'the Boss, a great explorer, a great leader and a good comrade.’

The success of the 1907-1909 Nimrod expedition raised Shackleton’s profile; the international science community and royalty feted him and invited him to lecture. The miniature medals below include examples he received from Sweden, Denmark, Russia, Italy and Norway, as well as his Royal Victorian Order. Emily requested the wartime medals after his death.

However, he also had a reputation for not being entirely trustworthy with money, borne out by the aftermath of each expedition, where he struggled to repay the debts and loans.

He was seen as inconsistent and restless. This was a specific criticism by Elspeth Beardmore, the wife of the main sponsor of the 1907 expedition. It was a criticism Shackleton took to heart, stating that the Nimrod Expedition was to prove her wrong.

Even Dr Eric Marshall, who had accompanied Shackleton on that expedition to within 97 nautical miles of the South Pole, was critical of him in private and public. This was mostly about him as a person rather than his organisational and leadership skills.

Shackleton's legacy – 100 years on

Shackleton’s reputation has fluctuated over the decades since his death. During the early years, his legacy was overshadowed not just by the death of Captain Scott, but also by people's experiences and sacrifices during the Great War.

There was an element of tribalism too: being either a Scott man or a Shackleton man – although some managed to straddle both camps – had an impact on how both men were perceived.

More recent writers have had to address this complexity within Shackleton’s personality. There is a greater appreciation now of the impact his polar expeditions and the effect that his restlessness in civil society had on his family, especially his wife Emily. These writers too have delved into the planning and funding of Shackleton’s expeditions and his relationship with Scott, especially the agreement in 1907 that Shackleton would not use McMurdo Sound as a base – which he subsequently did.

His reputation was burnished when historical figures became popular in leadership course programmes – including at the National Maritime Museum where he was part of the 2007 Leading Lives A-Level Business Studies course.

In this context, it is not his success or failure that matters, but his leadership style at critical points on his expeditions. Examples include his risk assessment to turn back in 1909 when his party was so close to the South Pole, as well as the extraordinary way he saved the crew of Endurance in 1916.

However, Sir Ranulph Fiennes, our most experienced polar explorer, takes a more measured view in his recent biography of Shackleton. While not questioning this brilliance, he raises the point that some situations were of Shackleton’s own making due to initial poor planning or being overly optimistic that events would pan out.

Author Michael Smith makes a similar observation, criticising Shackleton’s lack of technique in using dogs and skis when they clearly worked, as well as his impatience at the finer detail, which left him short of money and having to manage the impact of hurried preparation.

For a Museum, Shackleton plays many parts. He is the driver for broad sweep narratives and a starting point for looking at wider stories about his expedition members. His reputation as a leader during the ‘Heroic Age of Exploration’ is wrapped up with those of Scott, Mawson and Amundsen. Moreover, his polar exploration, like Scott’s, links to questions around scientific understanding, international geo-politics and nationalism.

Perhaps Shackleton’s reputation is best summed up by Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who served with Scott on the 1910 British Antarctic Expedition (Terra Nova). In the preface to his book about that expedition, The Worst Journey in the World, he wrote:

For a joint scientific and geographical piece of organisation, give me Scott; for a Winter Journey, Wilson; for a dash to the Pole and nothing else, Amundsen: and if I am in the devil of a hole and want to get out of it, give me Shackleton every time. They will all go down in polar history as leaders, these men.

Written by Jeremy Michell, Senior Curator of Maritime Technologies at the National Maritime Museum