What is an invasive species?

An invasive species is an animal or plant that causes disturbances or negative changes in a new environment where it isn’t normally found.

They can be found in all ecosystems but are a big problem in the ocean, because there are no physical boundaries from one part to the next. Once they become established in their new home, removing them becomes a complex and expensive challenge.

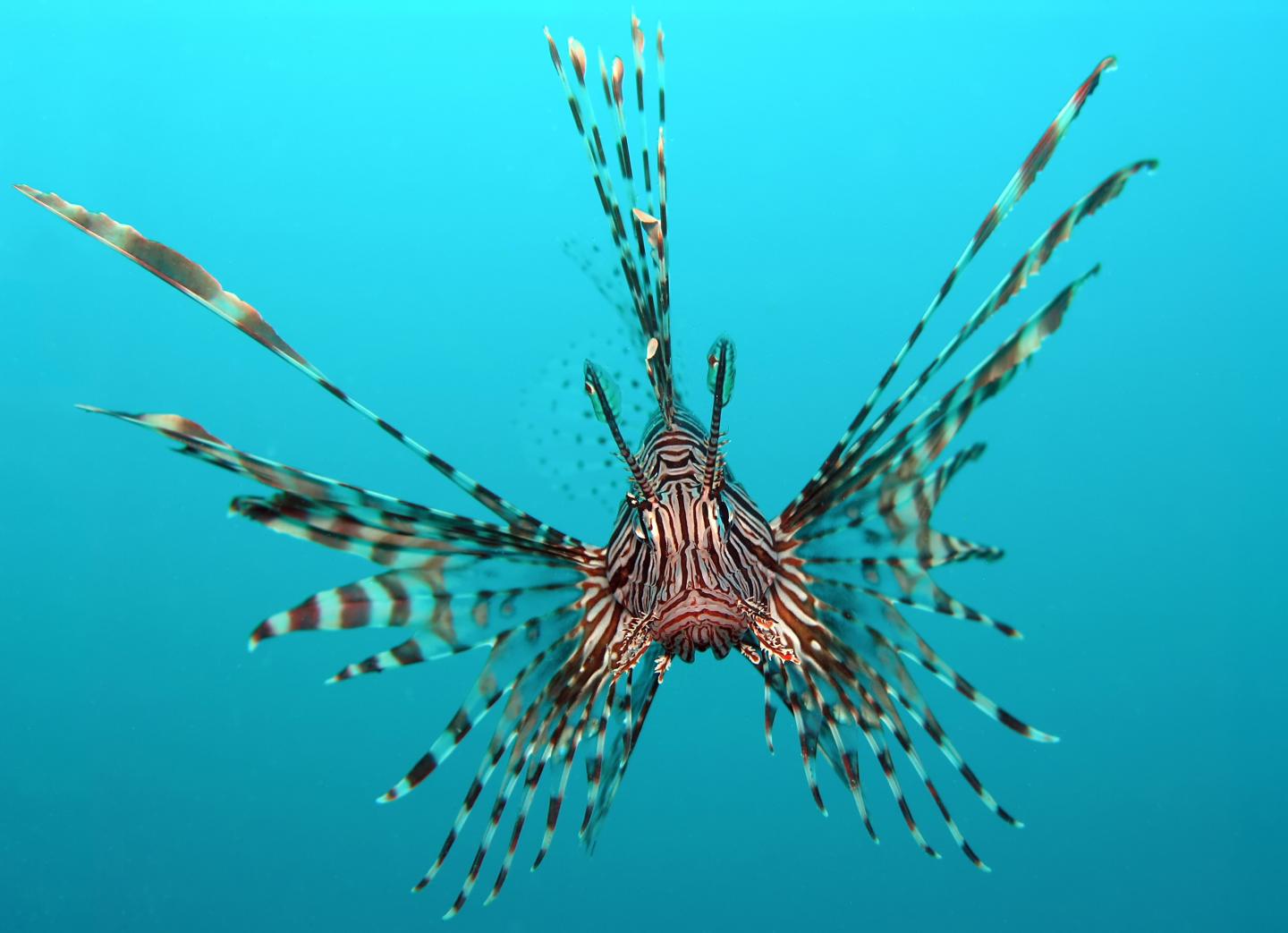

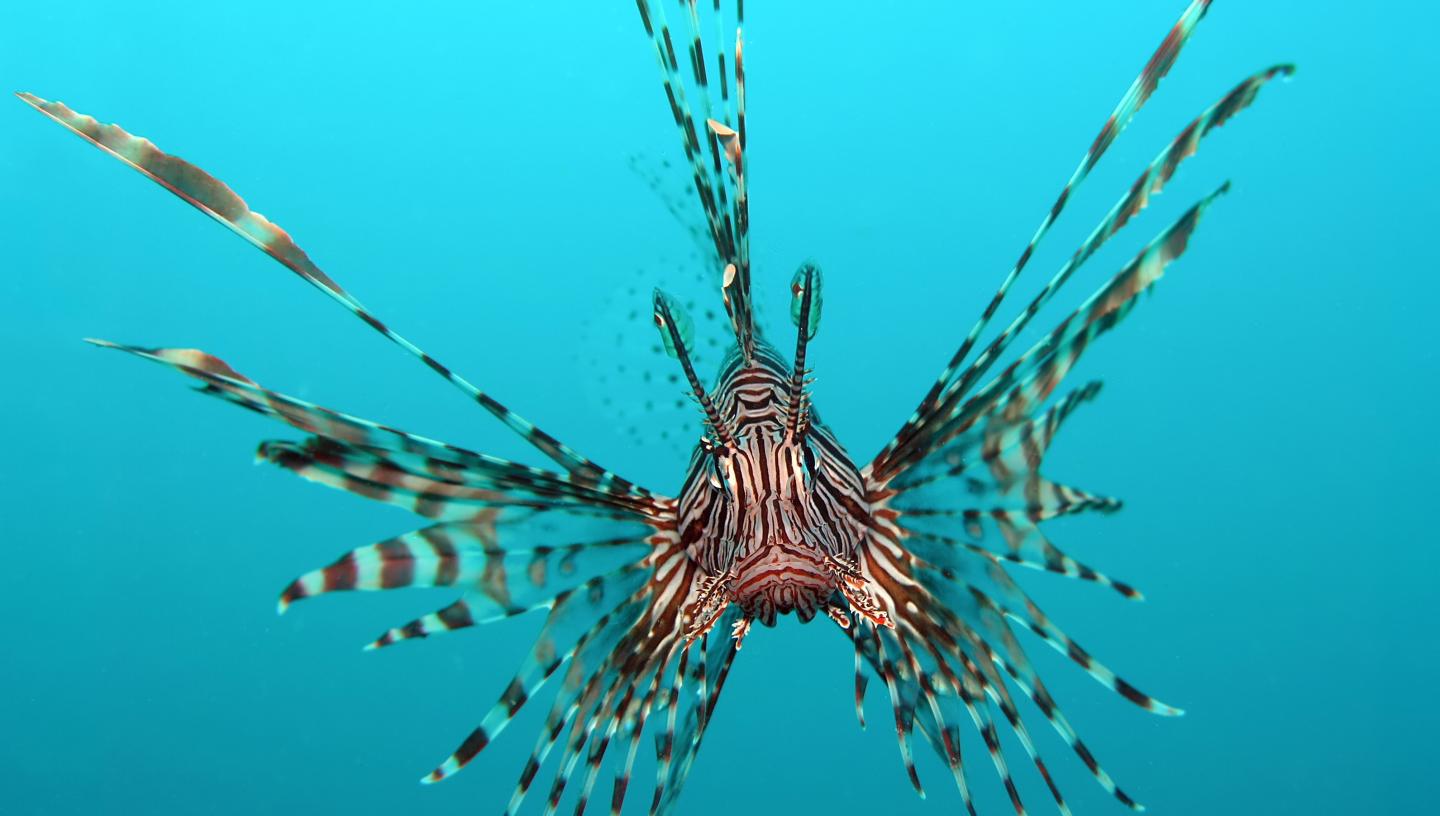

Examples of invasive species in the ocean include the lionfish, the zebra mussel, the Chinese mitten crab and the signal crayfish.

Each of these have invaded in a different way. These methods of invasion will be looked at below, as we try to understand how marine invasive species have found their new homes, many here in the UK.

Can you spot the scorpionfish?

The spotted scorpionfish is a master of disguise! But in this photo, the invasive species is much more obvious: the orange cup corals in the foreground at the bottom of the image are outcompeting native corals in the Atlantic.

Image Credit: National Marine Sanctuaries, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

How do invasive species arrive in the first place?

Invasive species are usually physically small, breed quickly, and can survive a long time as a small population. This makes species such as mussels and seaweed particularly good at invading new environments.

These movements are often facilitated by human activity, which is nothing new: accidental introductions have been noted for as long as humans have been using the ocean for travel and transport.

However, developments in maritime trade and changes in our global climate have made managing invasive species more challenging.

The aquarium trade

Many aquatic species are traded for use in aquariums, referred to as the ornamental fish industry.

Thanks to globalisation, buying and selling of ornamental fish happens everywhere. These animals are often dumped into open water when they become unwanted.

One of the most famous examples of this follows the success of the children’s animated show, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The late 1980s saw millions of red-eared sliders become pets around the world – before many were dumped into the wild when their owners didn’t want them any longer. They are now listed in the 100 World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species list.

This is also what happened with the lionfish (image above).

Native to the Indo-Pacific, these beautiful creatures were popular in aquariums around the world, particularly in the Western Atlantic and the Caribbean, where they now pose a huge threat to native biodiversity.

Despite a report in 1992 suggesting Hurricane Andrew caused a mass release from a nearby aquarium, lionfish sightings in Florida date back to 1985, making the invasion most likely due to lots of smaller releases. Their presence as an invasive has recently been reported in the Mediterranean, likely for similar reasons.

Fish farms

Aquaculture is the practice of farming fish and other aquatic organisms which are popular for humans to eat, such as salmon and crabs. These farms are found all over the world, making food locally available for global populations.

The signal crayfish was introduced through aquafarming to UK waters in the 1970s to be reared for restaurants and supermarkets. However, they very quickly became established in the wild.

Signal crayfish produce lots of offspring and eat anything they can get their claws on. They also carry a disease called the crayfish plague, which is lethal to the native British crayfish species, the white-clawed crayfish. As well as being directly harmful to British species, their burrowing method has caused the erosion of riverbanks throughout the country.

To prevent the spread of aquaculture species outside of their farming areas, some countries have a list of permitted species, and aquaculture facilities must obtain permits for each species they plan to farm. Health inspections and transport permits, as well as regular inspection of aquafarms, can reduce the risks of an accidental escape.

Ballast water

Ballast water is pumped in and out of ships to improve stability and balance when loading and unloading cargo. It has been used in commercial vessels since the late 19th century. Prior to this, ballast to give stability was done with heavy rocks and stone.

Ballast water is taken from the port the ship is in, before moving to another port to be deposited, where new water is pumped in – and the cycle continues. This ballast water contains a mixture of species that can be found in the port, taking them as cargo to the next destination.

The Chinese mitten crab was brought to UK waters through ballast water, via ships coming in from East Asia. These crabs burrow into riverbanks, making them unstable. They have affected fishing areas in Europe since the beginning of the 20th century, by directly competing for food with local species – and sometimes eating them! They were first sighted in the River Thames in 1935 and are now seen regularly.

Ballast water now undergoes treatment, such as filtering and disinfecting, to avoid pollution of seawater and movement of invasives. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has been involved in designing and implementing these standards, to reduce the chances of species reaching new destinations.

Objects in focus

See some of the objects relating to biofouling and ballast in the National Maritime Museum's collections

Biofouling

As ships travel through the water, living things like barnacles and algae stick to the hull of the ship.

Historically, seafarers removed these hitchhikers as quickly as possible by scraping boats in a dry dock, before they inhibited the vessel's performance. Covering the hull of a ship with protective metals like lead or copper was relatively common, and dates to the Greeks and the Romans.

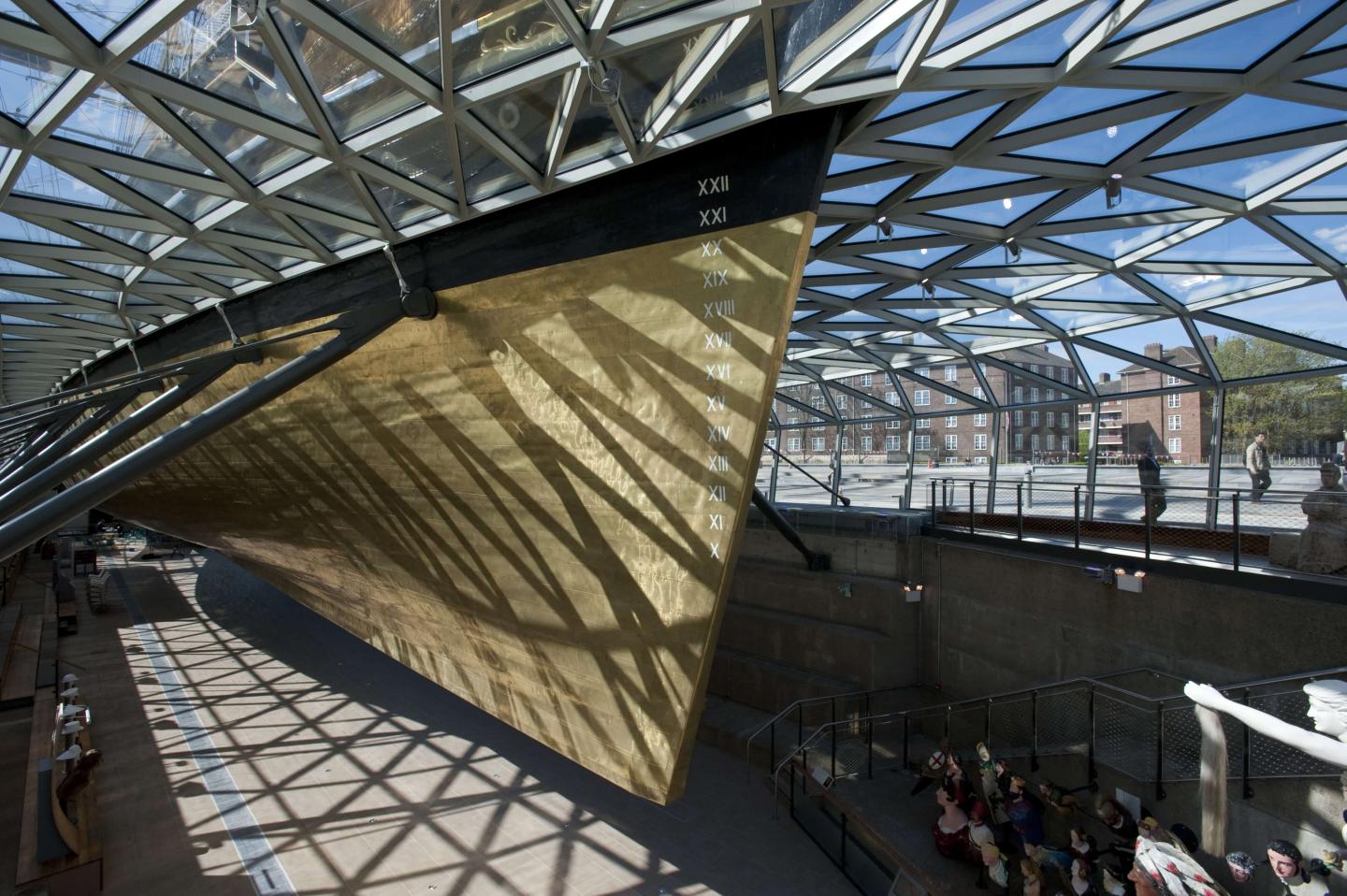

The Cutty Sark prioritised anti-fouling, by adding sheets of Muntz metal – a brass alloy made of copper and zinc – to its hull. You can still see what this sheathing would have looked like by visiting the ship in Greenwich.

Zebra mussels have become one of the most prolific invasive species, seen in North America for the first time in the late 20th century. The expansion of canals and recreational boating saw an explosion of zebra mussels across nearly every body of water in the United States.

Anti-fouling paint is commonly used on the hulls of ships to prevent unwanted wildlife. They work by releasing chemicals that are toxic to marine life.

Yet as well as this, they can be very damaging to the surrounding water, and the chemicals can accumulate in port regions.

Communities now encourage and enforce boat cleaning with fresh water if travelling between water systems. Programs such as ‘Clean Boats, Clean Waters’ in Michigan educate boaters and use volunteers to inspect boats.

Hitchhiking on marine debris

Like the biofouling of ships, marine invasives can travel by attaching themselves to debris, like plastic.

Plastic of all shapes and sizes is found all over our ocean, even in the deepest parts of the Mariana trench, 11,000 metres beneath the waves. Due to their light weight and density, this debris can travel great distances, and often takes hitchhiking species with it. These ‘rafting’ species have been known to travel hundreds of kilometres on masses of seaweed, but the increased dumping of human rubbish into the sea encourages these movements still further.

The Suez Canal is one of the biggest corridors of plastic movement, with around 455 invasives listed – thought to have travelled through the canal by rafting on plastics. Plastic debris studied on Easter Island found a crab species native to South Africa, over 10,000 km away.

This issue can only be tackled by solving the problem of marine debris itself. Currently, large scale clean-up operations are the best option, although have a minimal impact as humans continue to dump waste into the ocean. Reducing our impact by reducing our rate of consumption and encouraging re-use and re-cycling will have a massive impact in every part of our lives.

Species invade new environments in many ways. The history of maritime technologies, such as copper bottoming, demonstrates that the problem of invasive species has existed for years, even if the extent of their impact was unknown.

Our changing climate, especially our warmer seas, are only making things worse, with changing temperatures moving species towards the poles. The UK has lost some cold-water species almost entirely, such as the tortoiseshell limpet, to colder northern waters.

The presence and movement of invasive species is just another example of how humans are affecting our aquatic environment, and how important is it that we look after it.