In this blog we look at a beautifully illustrated account of some eruptions of Mount Vesuvius and Mount Etna by the British Envoy Extraordinary to the Court of Naples, Sir William Hamilton.

Diplomat, collector, volcanologist

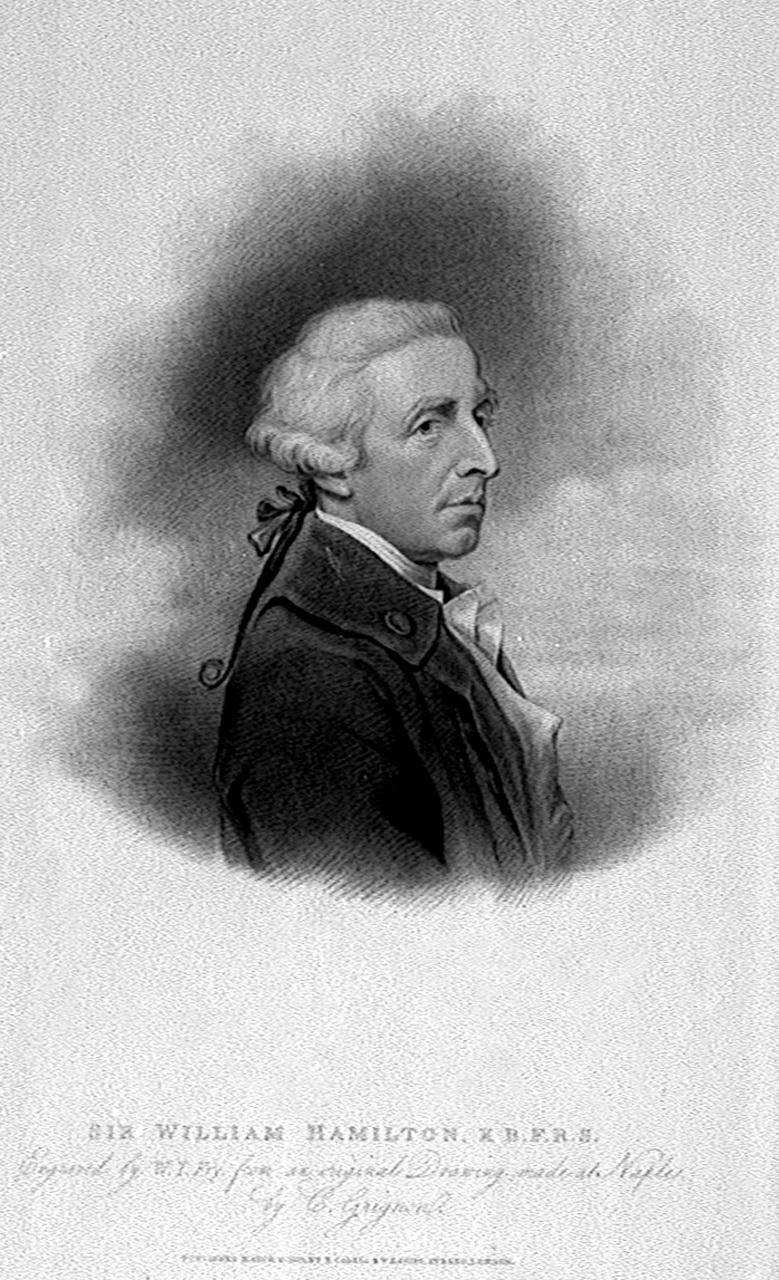

One of the treasures of the Caird Library is a copy of Campi Phlegraei by Sir William Hamilton (1731-1803), from the Jean Kislak Collection.

Sir William Hamilton is probably best remembered today as the husband of Emma Hamilton, but he was also a diplomat, an art collector, a collector of antiquities and a man of eclectic interests, one of which was volcanology.

His interest in volcanology developed after he was posted to Naples as the British Envoy Extraordinary. There were several eruptions of Vesuvius whilst Hamilton was resident in Naples, and he recorded the details and described events in letters to members of the Royal Society. It is these which are published in Campi Phlegraei.

In the book’s dedication to Sir John Pringle, Hamilton notes that ‘Since my return to this country, in January 1773, I have continued with assiduity my observations upon Mount Vesuvius, and the many ancient Volcanick productions in this Neighborhood.’

Hamilton also conducted tours of volcanic sites for distinguished visitors. In all, he ascended Vesuvius’s crater on in excess of 65 occasions, though he was quite aware of the dangers.

‘There is no doubt,’ he writes in the dedication, ‘but that the Neighborhood of an active Volcano, must suffer from time to time the most dire calamities, the natural attendants of earthquakes, and eruptions; Whole cities, with their inhabitants, are either buried under showers of pumice stones and ashes, or overwhelmed by rivers of liquid fire’.

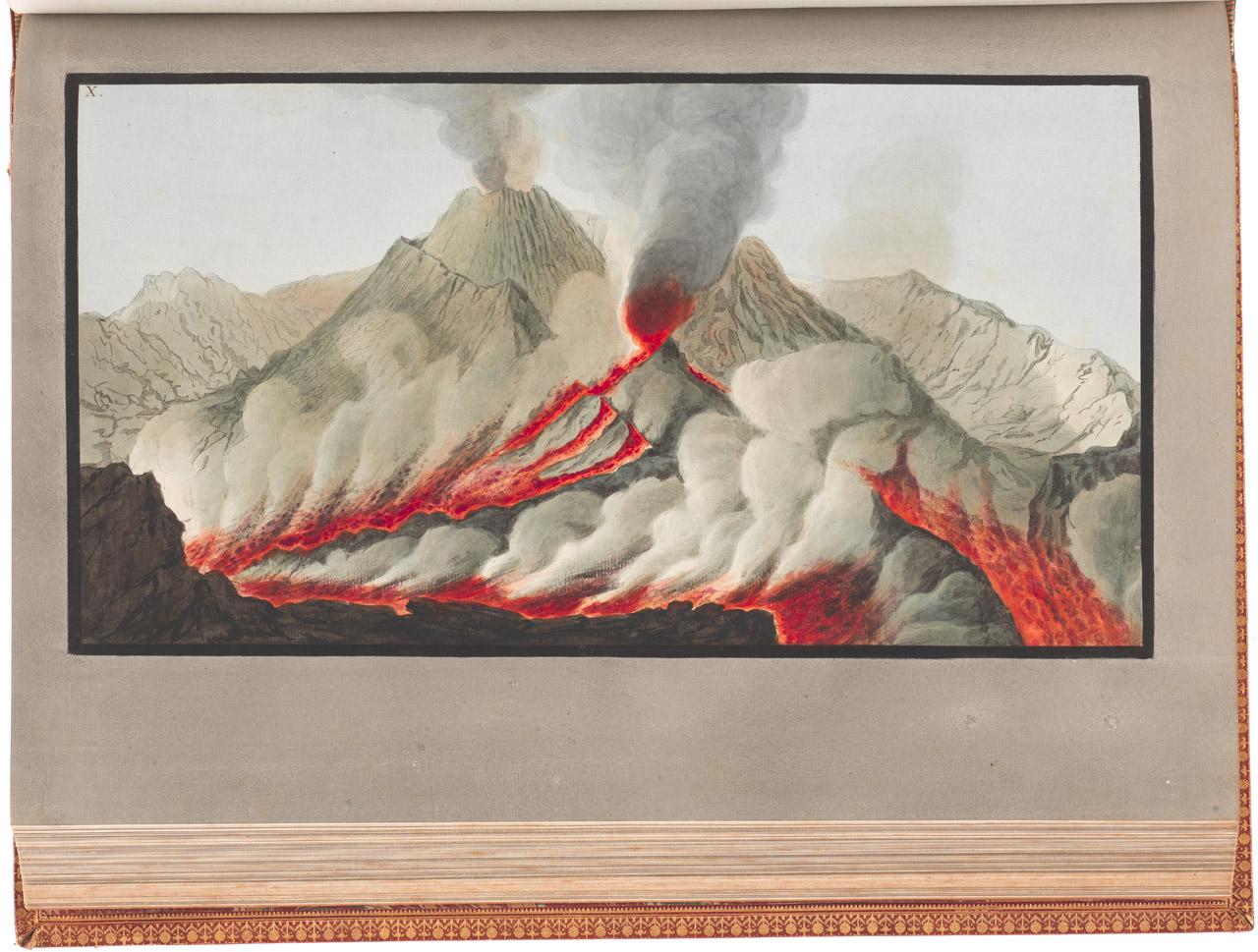

Hamilton also states that he was ‘still sensible of the great difficulty of conveying a true idea of the curious country I have described, by words alone, particularly to those who have not had an opportunity of visiting this part of Italy’. He therefore commissioned the artist Peter Fabris to draw and colour locations which are described, and these provide the striking images contained in the volume.

Eyewitness accounts

Hamilton’s words provide detailed eyewitness descriptions and reveal how close he must have got to the eruptions. His account of Vesuvius’s eruption in the spring of 1766, observed that:

On Good Friday, the 28th of March, at 7 o’clock at night, the lava began to boil over the mouth of the Volcano, at first in one stream; and soon after, dividing itself into two, it took its course towards Portici. It was preceded by a violent explosion, which caused a partial earthquake in the neighbourhood of the mountain; and a shower of red hot stones and cinders were thrown up to a considerable height.

Hamilton states that he ‘left Naples’ and:

passed the whole night upon the mountain; and observed that, though the red hot stones were thrown up in much greater number and to a more considerable height than before the appearance of the lava, yet the report was much less considerable than some days before the eruption. The lava ran near a mile in an hour’s time, when the two branches joined in a hollow on the side of the mountain, without proceeding further. I approached the mouth of the Volcano, as near as I could with prudence; the lava had the appearance of a river of red hot and liquid metal, such as we see in the glass-houses, on which were large floating cinders, half lighted, and rolling one over another with great precipitation down the side of the mountain, forming a most beautiful and uncommon cascade. The color of the fire was much paler and more bright the first night than the subsequent nights, when it became of a deep red, probably owing to its having been more impregnated with sulphur at first than afterwards.

Hamilton records that on the next day, ‘the mountain was very quiet and the lava did not continue’, but that on 30 March the lava began flowing again, ‘whilst the mouth of the Volcano threw up every minute a girandole of red hot stones, to an immense height.’

It is interesting that in his attempt to convey in words the spectacle he had witnessed, Hamilton makes comparisons with phenomena his readers may have seen for themselves, such as fireworks or the molten metals of manufacturing processes.

Hamilton passed the night of the 31st on the mountain, when, he says:

the lava was not so considerable as the first night; but the red hot stones were perfectly transparent, some of which, I dare say of a ton weight, mounted at least two hundred feet perpendicular, and fell in, or near the mouth of a little mountain, that was now formed by the quantity of ashes and stones, within the great mouth of the Volcano, and which made the approach much safer than it had been some days before, when the mouth was near half a mile in circumference, and the stones took every direction.

'Rivers of fire'

Not everyone knew what distance they needed to keep from the spectacle. Hamilton states that ‘Mr Hervey, brother of the Earl of Bristol, was very much wounded in the arm some days before the eruption, having approached too near, and two English gentlemen with him were also hurt.’

The lava remained present on the mountainside for the following nine days, sometimes forming as many as four branches, but did not descend any lower. Then, on 10 April, it erupted again, but on the side nearest the Torre dell’Annunciata. Hamilton found its exit point ‘within about half a mile of the mouth of the Volcano’ where its width ‘was about ten feet’, and describes the manner of its exit as ‘like a torrent, attended with violent explosions, which threw up inflamed matter to a considerable height, the adjacent ground quivering like the timbers of a water-mill; the heat of the lava was so great, as not to suffer me to approach nearer than within ten feet of the stream’.

The lava split ‘into three branches’ which Hamilton describes as ‘rivers of fire’. These ‘communicated their heat to the cinders of former lavas, between one branch and other, [and] had the appearance at night of a continued sheet of fire, four miles in length, and in some parts near two in breadth.’

Parts of the neighbouring area suffered damage. Hamilton writes that some of the lava went underground and emerged again: ‘In this manner it advanced to the cultivated parts of the mountain; and I saw it, the same night of the 12th, unmercifully destroy a poor man’s vineyard, and surround his cottage.’ Vineyards were ‘greatly damaged’ by ‘quantities of small ashes and pumice stones’ which were ‘thrown up’ by the volcano.

Hamilton visited the mountain on several subsequent occasions in the following weeks. As late as 3 June, he found that there was still some lava present. Once the eruption ceased, Hamilton ‘examined the crater, and the crack on the side of the mountain’. He took specimens of ‘some very curious salts and sulphurs’ (there are also images of volcanic rocks in the book). Some of the rock specimens which Hamilton collected are now part of the Natural History Museum’s collection.

Campi Phlegraei was published bilingually in English and French in 1776. It helped popularise volcanology and a visit to Vesuvius became an essential part of the Grand Tour. Bound with our copy is a Supplement about the great eruption of Mount Vesuvius in August 1779.

Further reading

Fields of Fire: a Life of Sir William Hamilton by David Constantine, London: Orion, 2001 (Caird Library ID: PBF1050) – available on open access in the Caird Library

‘Sir William Hamilton (1731-1803)’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (available to access online in the Caird Library Reading Room)