For many, Charles Dickens is synonymous with Christmas jollity. However, there was a darker side to Dickens’ work. Not only did he repeatedly refer in his novels and articles to the contemporary filth of the Thames, which culminated in the Great Stink crisis of 1858, he was also actively involved in kick-starting the reform programmes to resolve the issue.

The Great Stink

Since the Industrial Revolution there had been massive urban growth without the essential planning policy to support it. The population of London had increased from approximately one million in 1800 to two and a half million in 1850.

Parliamentary reforms of municipal government in the 1830s had failed to resolve the issue, and there was little sense of civic responsibility. Corporations were elected by narrow-minded and self-interested voters, wanting cheap government with low spending on drains and water supplies.

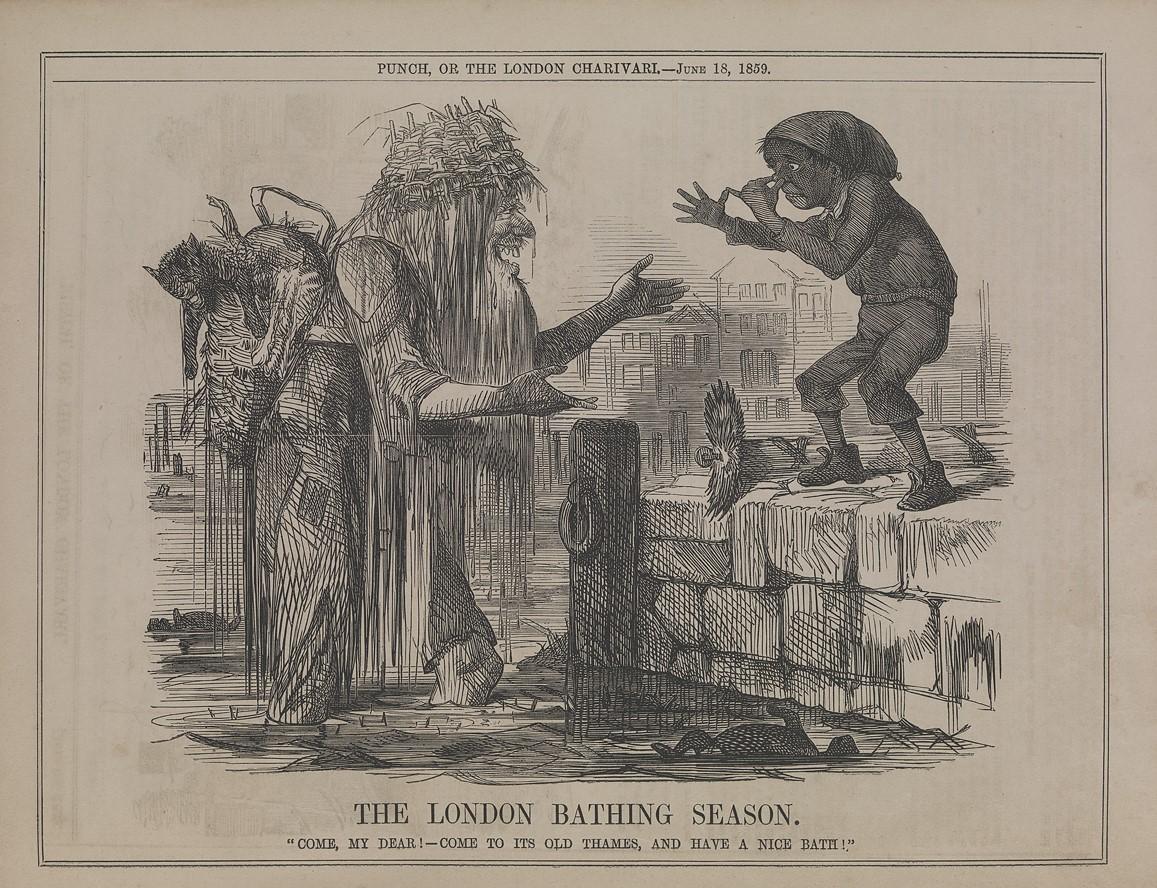

The problem was ironically compounded by the supposedly more hygienic introduction of water closets, in place of chamber pots and cesspits. Sewers originally intended to take only rainwater now carried, and dumped, untreated raw sewage into the Thames, on top of the industrial and domestic rubbish.

By 1857, some two hundred and fifty tons of faecal matter entered the Thames daily. It was from this source that the eight private water companies then extracted drinking water for London.

Cholera outbreaks in 1848 and 1854 were correctly attributed by Doctor John Snow to the infected water supply, but his evidence was seen by most contemporaries as novel and unsound, sticking to the belief that cholera was a result of ‘miasmas’ or poisonous gases, emitted by dead or decaying matter.

The Metropolitan Commission of Sewers had responsibility for the worsening situation but lacked the power to impose the required taxes to sort it. All central government attempts to address the issues were seen as despotic interference in local liberties.

This environmental crisis culminated in the Great Stink of 1858. In June, while crossing the river at Deptford to inspect a new ship, the toxic smell from the Thames was so horrific that Queen Victoria had to hold her nose.

In the House of Commons, the curtains were soaked in chloride of lime to try and make it possible for parliamentary sittings to be endured. Unsurprisingly, as the MPs thought they were being fatally poisoned, a bill was rushed through and became law in just eighteen days, providing money to construct a massive new sewer system. The Times newspaper reported that Members of Parliament had been ‘forced by sheer stench’ to sort the issue of the Thames.

Sir Joseph William Bazalgette, the Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, was hired specifically for the project; an extensive underground system of sewers which would join up the existing municipal drains, and funnel the waste far downstream, via pumping stations at Deptford and Abbey Mills, dumping it into the Thames Estuary at high tide.

Two of the sewers were to run along the north and south banks of the Thames, providing an opportunity to build large ‘embankments’ above the ground, and an underground tube line below. The embankments narrowed the river, reclaiming approximately twenty-two acres. Officially opened by the Prince of Wales in 1865, it was not finished until 1875.

Dickens and the Thames

Dickens was born by the sea (in Portsmouth) and spent his early life in London and on the Kent coast. As Peter Ackroyd noted in his 1990 biography, it is hard to think of a novel of his ‘that does not take place within earshot of the river or of the tides’.

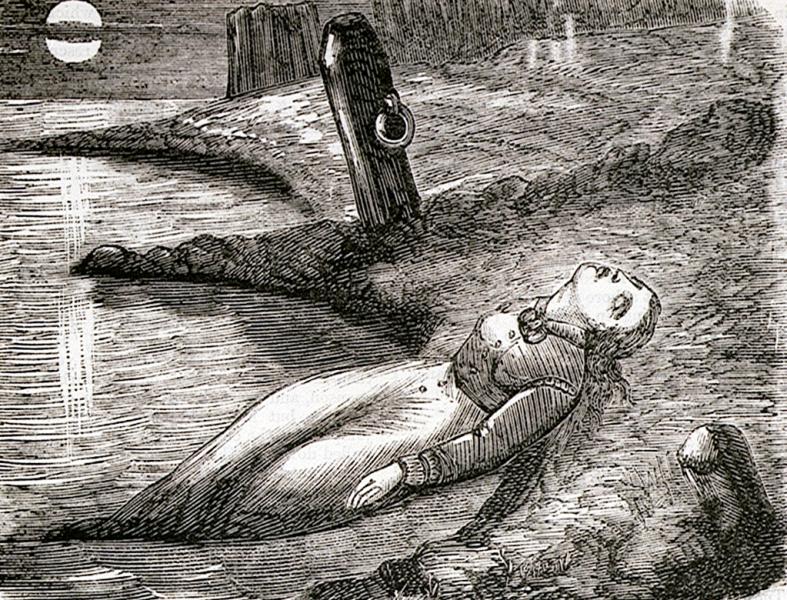

The Thames is a recurrent presence in Dicken’s novels and is rarely a pleasant phenomenon. Martha, in David Copperfield (first published in 1849), speaks of the Thames when she is considering drowning herself:

“Oh, the river!” she cried passionately. “Oh, the river!”

“Hush, hush!” said I. “Calm yourself.”

But she still repeated the same words, continually exclaiming. “Oh, the river!” over and over again.

“I know it’s like me!” she exclaimed. “I know that I belong to it. I know that it’s the natural company of such as I am! It comes from country places, where there was once no harm in it—and it creeps through the dismal streets, defiled and miserable—and it goes away, like my life, to a great sea, that is always troubled—and I feel that I must go with it!”

In Little Dorrit (published 1855), London is ‘where people lived so unwholesomely that fair water put into their crowded rooms on Saturday night, would be corrupt on Sunday morning’ and ‘Through the heart of the town, a deadly sewer ebbed and flowed, in the place of a fine fresh river’.

In Dickens' final completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, written six years after the Great Stink in 1864, the Thames remains in Dickens’ mind as a place of putrefaction and death. In the opening scene, set on the river, Gaffer and Lizzie Hexam are scavenging for bodies in ‘a boat of dirty and disreputable appearance’ described as ‘allied to the bottom of the river rather than on the surface, by reason of the slime and ooze with which it was covered, and its sodden state.’

Dickens and reform

It wasn’t just in his novels that Dickens addressed the issue.

When the reformer and early advocate of public health Edwin Chadwick started work on his Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, Dickens and his brother-in-law Henry Austin, himself a leading sanitary reformer, not only submitted evidence but also offered Chadwick advice on how to best present his findings.

When published in 1842, the report created the impetus for reform, focusing on proper drainage and sound engineering. Chadwick had a long-lasting effect on Dickens and his subsequent work.

In 1848 Dickens joined the Health of Towns Association and following a visit in 1850 to Kew Bridge Pumping Station, wrote the following in Household Words, his weekly journal:

you admit that... only three companies filter; the deduction, therefore, is that two-thirds of the water supplied to Londoners is insufficiently cleansed. This indeed, is not a mere inference; we know it for a fact, we see it in our sewers, we taste it out of our caraffes.

Dickens and a water company official

But this does not wholly arise from the inefficient filtration of the six companies... the public is much to blame - though, when agitating against an abuse, it never thinks of blaming itself.

In 1851 Dickens made the following speech to the Metropolitan Sanitary Association:

Fifteen years ago some of the valuable reports of Mr Chadwick and Dr Southwood Smith, strengthening and much enlarging my knowledge, made me earnest in this cause in my own sphere; and I can honestly declare that the use I have since that time made of my eyes and nose have only strengthened the conviction that certain sanitary reforms must precede all other social remedies, and that neither education nor religion can do anything useful until the way has been paved for their ministrations by cleanliness and decency.

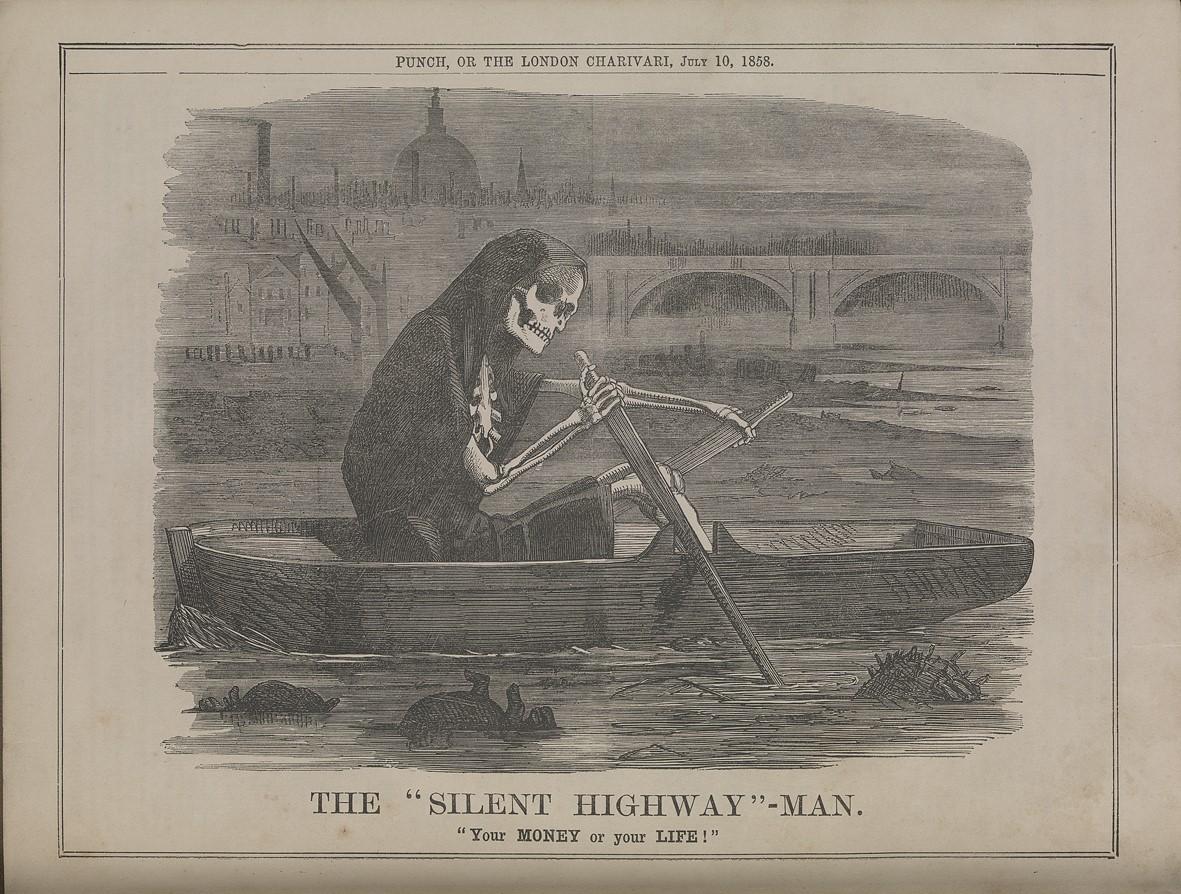

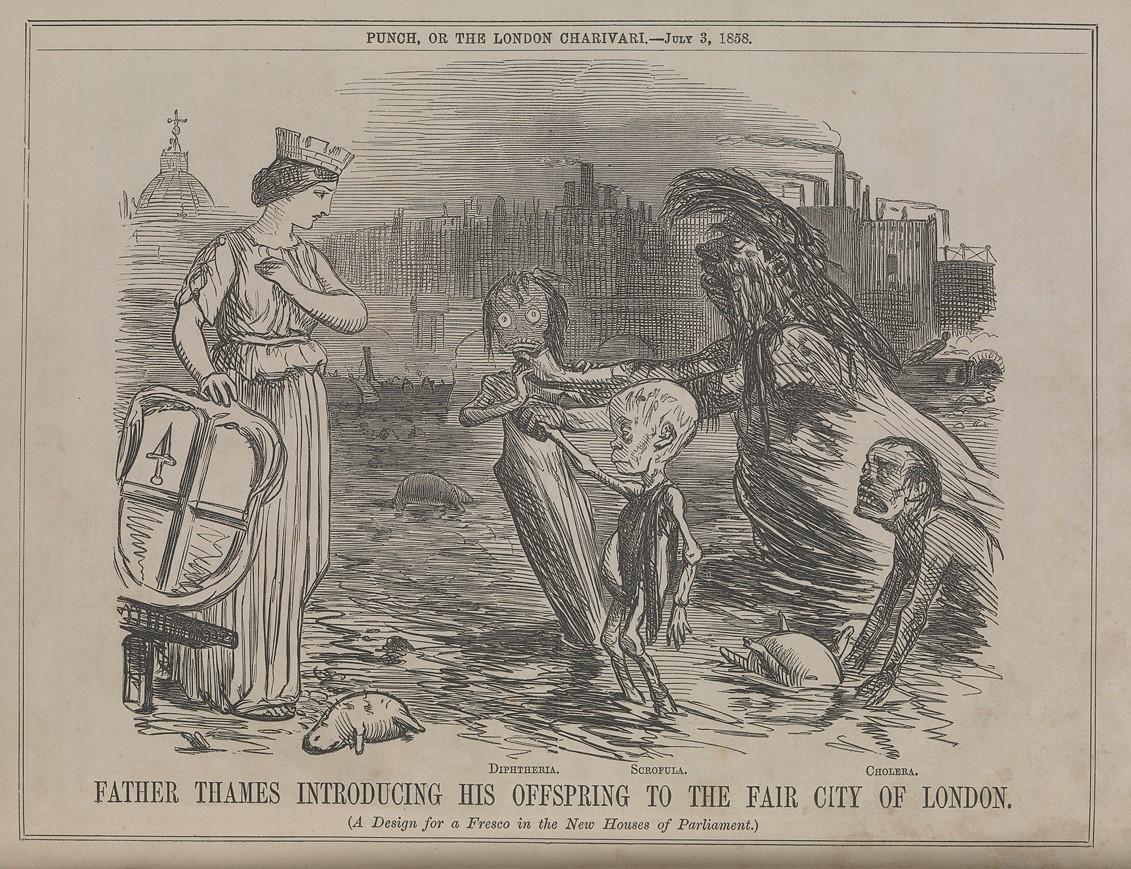

The same year, a short story called Father Thames appeared in Household Words. A Mr Beverage is taken by Old Father Thames on a journey down the river and through the sewers, with the aim of educating him on the filth and danger of the Thames’ water for all Londoners. This Punch cartoon could easily have taken inspiration from Dickens' story.

Beverage represents the bigoted upper and middle classes, who don’t believe the problem directly affects them and so refuse to do anything about it. Unfortunately, unlike Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, Beverage refuses to change his opinion, incurring the wrath of the Thames:

For every dead dog and cat that is flung into my bosom, there’s a typhus patient – perhaps a dozen; for every slaughter-house, fish-market, or graveyard near my banks, there’s a dozen scarlet fever patients – perhaps a hundred; for every main sewer draining into me, there is a legion of cholera patients in due season. I have been deeply injured, but I am amply avenged.

In an 1855 Dickens satire, the evocatively named 'Cess-cum-Poolton' is in the middle of a local election campaign. The candidate rallies the voters:

Ratepayers, Cess-cum-Poolton! Rally around your vested interests. Health is enormously expensive. Be filthy and be fat. Cesspools and Constitutional Government! Gases and Glory! No insipid water!

During the Great Stink, in July 1858 an article appeared in Household Words called A Way to Clean Rivers:

We pour it [the filth] out into the rivers flowing through our towns, and pollute them as never before have rivers been polluted since the world was made… The Thames which, before reaching Loudon, is polluted by the drainage from seven hundred thousand people, and in London deposits the filth of hundreds of thousands upon mud-banks exposed daily at low water, and in these hot days, festering at the heart of the metropolis. These rivers represent the difficulty that has to be met before the new order of things can be regarded as established with a proper harmony in all its parts...

Dickens’ contribution in popularising scientific concerns through his work and raising public awareness and hence forcing political action cannot be underestimated; the Thames and the Embankments we enjoy today are, to some extent, due to him.

Further reading

The Caird Library and Archive contains copies of Punch (1843-1951) and the Illustrated London News (1842-1989), though our twentieth century holdings are incomplete. Both periodicals reported on the condition of the Thames and the work to improve it.

Search the library catalogue to place your request. You can explore the Illustrated London News online via our electronic access in the Reading Room.