At the end of the 18th century, Bounce was not only a beloved companion to one of our most famous admirals, but considered by his owner the perfect naval dog - and more intelligent than some of his officers!

Collingwood's early life

Cuthbert Collingwood entered the Navy in 1760, at the age of 12. In 1775, he was made a lieutenant, following involvement in the Battle of Bunker Hill, which marked the start of the American War of Independence.

In 1773 Collingwood met Horatio Nelson and they became firm friends. In 1785 they made these portraits of one another while they were both posted in the West Indies.

From 1786 until 1793, Collingwood was predominantly in England apart from one trip to the West Indies, over the winter of 1790-1791. He took advantage of this relative downtime to settle down and form important relationships. He married Sarah Blackett, the daughter of a Newcastle merchant and politician, in 1791, and they made their home at Morpeth, just 15 miles from Newcastle. But prior to that he had formed a strong bond with another companion.

Bounce was still only a puppy when Collingwood first took him to sea, referring to him as 'a charming creature, everybody admires him, but he grown as tall as the table I am writing on almost'. (1)

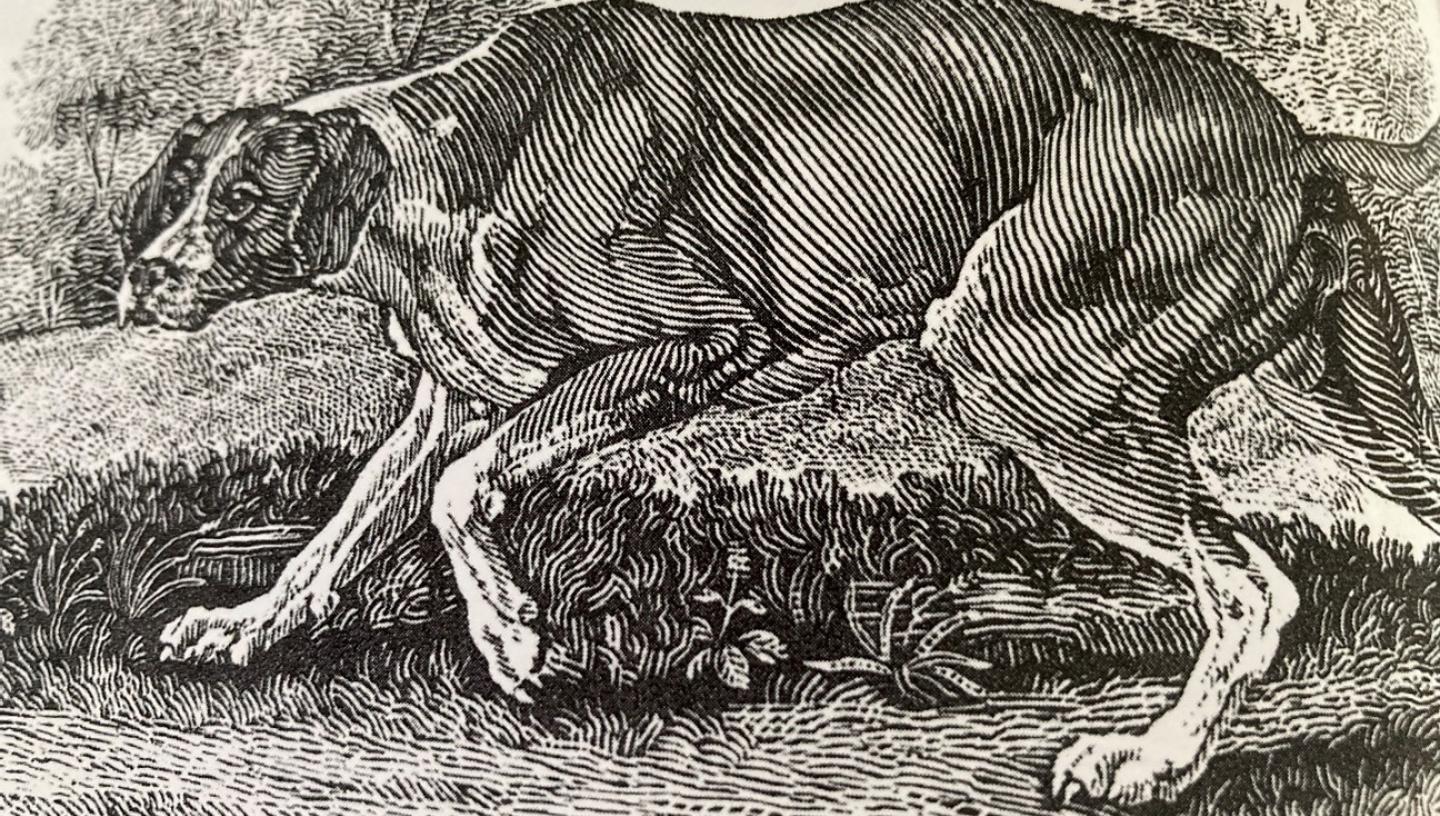

We don’t know what breed of dog Bounce was, but we do know he was relatively big and strong. He might have been a Spanish Pointer, such as the one in the engraving above, or possibly a Menorcan rabbit dog.

Collingwood loved to walk over the hills around Morpeth with Bounce by his side when on leave or half pay, but Bounce also showed decidedly aquatic strengths when he accompanied Collingwood to sea: 'My dog is a good dog, delights in the ship and swims after me when I go in the boat.' (2)

Bounce would regularly be mentioned in letters home not only to friends and family, but also often in more official documents, and would pass on regards in postscripts to the recipient’s dogs. In a letter to his wife regarding a young midshipman, Collingwood noted that he should be 'very sorry to put the safety of a ship and the lives of the men into such hands. He is of no more use here as an officer than Bounce, and not near so entertaining'. (3)

Midlife: a time of important battles

Bounce’s one weakness was an abhorrence of gunfire - not ideal when his owner was dedicated to achieving perfection in the art of naval gunnery. Bounce learnt to hide amongst the decks whenever he heard the marine’s drum beating to quarters.

It was fortunate he perfected this technique, as in the next few years there would be a lot of gunfire to contend with. This included the Battle of the First of June 1794, the Battle of St Vincent in 1797, and in 1805 there was of course the Battle of Trafalgar, at which Collingwood was second in command to his great friend Nelson.

Post Trafalgar

Following Nelson’s death, Collingwood not only became Vice-Admiral of the Red and a hereditary peer, he also became famous and revered as the heir to England’s Saviour, as demonstrated by this commemorative mug from 1806.

Collingwood was now Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean fleet, an appointment he held until his death. This glory and promotion did not go to Collingwood’s head. However, according to a letter he wrote to his wife, now Lady Collingwood, the same could not be said for Bounce.

I am out of all patience with Bounce. The consequential airs he gives himself since he became a right honourable dog are insufferable. He considers it beneath his dignity to play with commoners’ dogs, and truly thinks that he does them grace when he condescends to lift his leg against them. This, I think, is carrying the insolence of rank to the extreme, but he is a dog that does it. (4)

By 1807, Bounce was reported to be 'very well and very fat, yet he seems not to be content and sighs so piteously these long evenings, that I am obliged to sing him to sleep'.

Collingwood’s preferred choice of lullaby was a personalized parody of a song from Much Ado About Nothing;

Sigh no more, Bouncey, sigh no more,

Dogs were deceivers never;

Though ne’er you put one foot on shore.

True to your master ever. (5)

Writing later that year regarding the education of his daughters, Collingwood compared forcing 'upon them that which is repugnant to their nature ’tis like teaching a rook to sing or Bounce to play upon the fiddle – long labour lost – for though Bounce is a dog of talents, I suspect he wou’d make but a discordant fiddler'. (6)

The following summer he reported to his sister that: 'Bounce has been confined some days with sort of rheumatic gout which threatens a general debility. He is a present on a regime.' (7)

Both master and dog were feeling their age. Collingwood wrote to his wife:

Bounce and I seem to be the only personages who stand our ground. Many about me are yielding to the fatigue and confinement of a life which is certainly not natural to man (8)

Bounce died less than two months later, washed overboard during a storm. Collingwood wrote to his sister to tell her the sad news.

You will be sorry to hear my poor dog Bounce is dead. He fell overboard in the night. He is a great loss to me. I have few comforts, but he was one, for he loved me. Everybody sorrows for him. He was wiser than (many) who hold their heads higher and was grateful (to those) who were kind to him. (9)

The crew made a miniature casket and draped it with a union flag for a well-deserved burial at sea.

Bounce had spent a faithful 19 years with Collingwood, a far greater amount of time than Collingwood ever enjoyed with his beloved family, whom he had not seen for the last seven years having left England in 1803 never to return. The Admiralty had refused his repeated requests for leave, feeling he was irreplaceable in his command of the Mediterranean Fleet. Having finally been granted it he died en route home in 1810, only eight months after Bounce. Collingwood was laid to rest next to his great friend Nelson in St Paul’s Cathedral.

In the Archive Collections here at the National Maritime Museum we have a wide collection of items relating to Admiral Lord Collingwood, including much of his correspondence, which can be requested for viewing in the Reading Room of the Caird Library. One of my favourites is a secret letter book, which includes letters from October 1805 concerning the death of Nelson and an account of the Battle of Trafalgar.

References

The excerpts from letters are taken from:

The private correspondence of Admiral Lord Collingwood (RMG ID: PBE1862)

- (1) Letter to his sister Mary, dated Saturday, May 29th 1790, p26

- (2) Letter to his sister Mary, dated July 15th 1790, p28

- (6) Letter to his sister Mrs Stead, dated July 1st 1807, p213

- (7) Letter to his sister Mrs Stead, dated June 15th 1809, p282

- (9) Letter to his sister, dated August 13th 1809, p291

The life and letters of Vice-Admiral Lord Collingwood (RMG ID: PBD5394)

- (4) Letter to his wife, December 1805, p164

- (5) Letter to his wife, 1807, p180

- (8) Letter to his wife, June 1809, p219

Admiral Collingwood: Nelson's own hero (RMG ID: PBF6177)

- (3) Letter to his wife, July 1808, p257

Title engraving by Thomas Bewick of a Spanish Pointer taken from Collingwood: Northumberlan's heart of oak (RMG ID: PBF6057)