Discover the conservation story of the Armada Portrait's restoration, from the early research to the finishing touches.

In 2016 the National Maritime Museum acquired the famous ‘Armada portrait’ of Elizabeth I from the Tyrwhitt-Drake family, who are recorded as owning it since at least 1775. This followed an appeal to save it for the nation, generously supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Art Fund, Linbury Trust, Garfield Weston Foundation, Headley Trust and other major donors.

Where did the portrait come from?

As Senior Paintings Conservator at the Museum, this is a picture I have known in a professional capacity since 1987, when we first borrowed it for the exhibition we held in 1988 to mark the 400th anniversary of the Spanish Armada. We were also lent it again in 2003 for our Elizabeth show, marking the 400th anniversary of her death, and on both occasions we did minor stabilisation work on it. When it finally arrived as our own in September 2016, I was again asked to examine it, make recommendations for longer-term conservation options and, when these had been agreed, to carry out the work. The treatment took over six months.

I drew up a plan of action after extensive research, including liaison with colleagues in other institutions who either had direct knowledge of the painting, or had worked on similar ones. The portrait is painted on five vertical oak panels and to a ‘pattern’ that Elizabeth I herself would have approved. The artist is unidentified but there are two other versions, by different and also unidentified hands. One is in the Duke of Bedford’s collection at Woburn Abbey: the other is in the National Portrait Gallery but has been cut down on each side, leaving just the figure of the Queen with little around it. The Woburn Abbey painting is of particular interest as the two seascapes in the background depict earlier ships, more contemporary to the portrait than those in our version, which show shipping more in the style of the 1670s or 1680s.

The portrait's layers

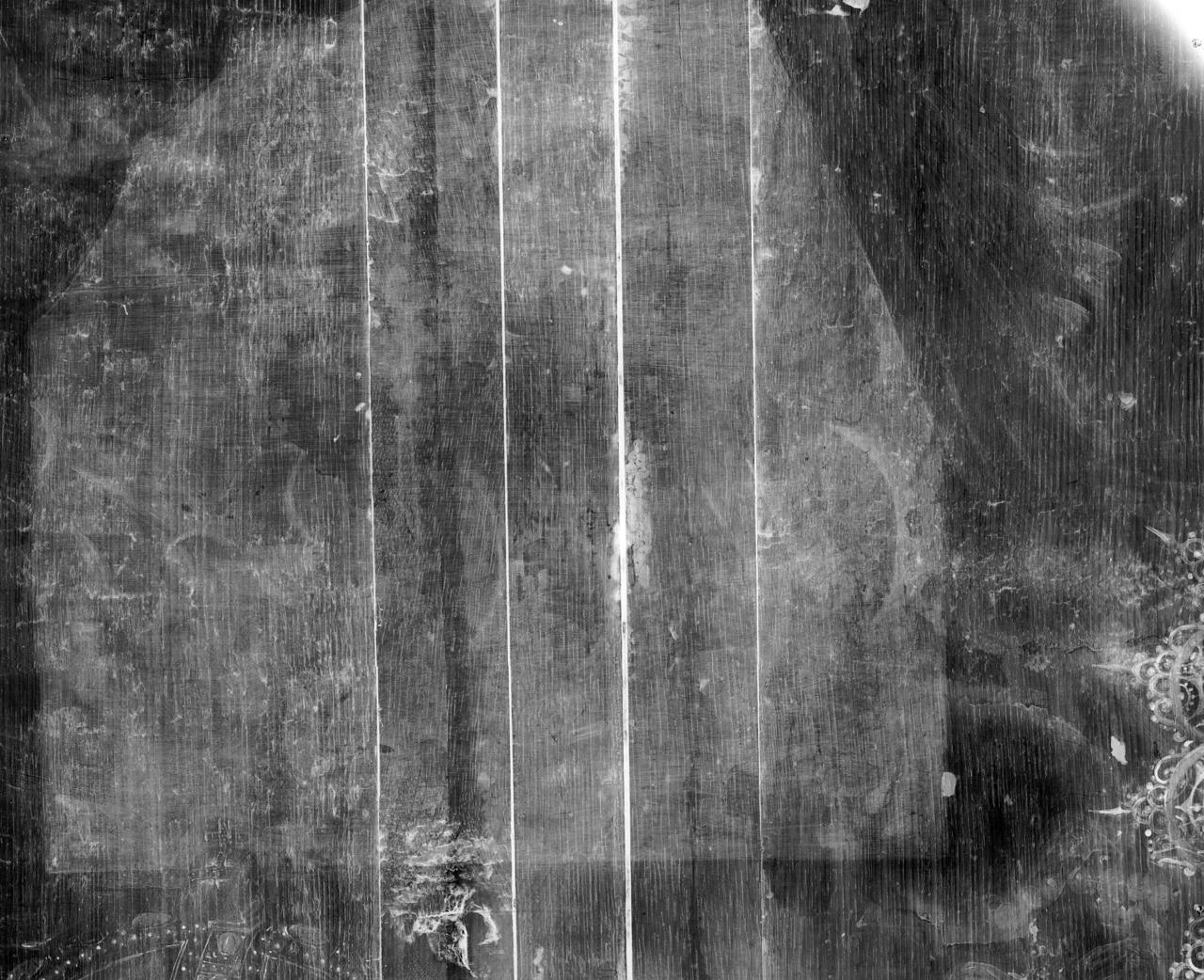

In 1987, when the painting first came to the Museum on loan, my examination of it included taking X-rays of Elizabeth’s head and the two seascapes. These showed that the latter had been painted over original compositions like those in the Woburn Abbey version. This has now been confirmed by more extensive work, made possible by an EU grant to have Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning carried out by Molab-Iperion from Italy. The macro-XRF shows in even clearer detail that the early, overpainted seascapes appear practically identical to the Woburn Abbey ones. We also know that the same was probably true of the NPG version, since it has also been X-rayed and shown to have fragments of the same compositions at its cut-down edges.

Our painting was covered in several varnish layers, two very discoloured, greatly obscuring the original colours. Tests showed that one layer was a pigmented 'toned' varnish, probably added by a restorer at some stage in the work’s history to give an `antique` look. After careful consideration, I recommended a full varnish removal, and of recent (i.e. 19th- and 20th-century) retouchings, but to leave the two 17th-century-style seascapes that have become part of this iconic painting and its history. Later examination found Prussian Blue in these sea pieces and also in the bows of the dress, some of which had early retouchings of a very high quality over some very early losses. Prussian blue was not in use until after 1710, which enabled us to date the repainted work more precisely, the intriguing upshot being that whoever did the new seascapes in the early 18th century seems to have been deliberately working in a late-17th-century style in his representation of the shipping.

Removing the varnish

Following thorough examination, documentation and photography, the cleaning process could begin. Tiny cleaning tests were carried out in discreet areas with a variety of solvents in various strengths, to determine the most dilute and most appropriate to be used. The varnish was removed slowly and methodically, and with it the later, easily soluble retouchings.

After I had completed the cleaning, a disfiguring filling in the Queen’s chin needed addressing. This was saucer-shaped, raised at the edges, smooth and with a dip in the middle; I levelled and textured it to make it less distracting. I also consolidated any raised or insecure areas.

At this stage I applied a synthetic isolating varnish. This serves to protect the original paint from new retouchings but also saturates the colours, giving back their vibrancy. The painting would have been varnished by the artist soon after completion, both as a protection but also to enrich the colours.

Retouching

The retouching I carried out was over the isolating layer and used the same synthetic resin and dry pigments. This resin will not discolour in the way natural tree resins do, and remains soluble in white spirit. The retouching was limited to areas of loss, filling and damage. After it was finished a final spray-varnish was applied, again using the synthetic resin.

The painting was then remounted in a microclimate frame. This helps to ensure that the vulnerable panel, so susceptible to fluctuation in temperature and humidity, is buffered from background changes. It is glazed with low-reflect glass, which additionally protects it from surface pollutants and accidental touching.

The painting was rehung in October 2017 in the Queen’s Presence Chamber of the Queen’s House at Royal Museums Greenwich.