Written by John Prescott, Cutty Sark volunteer

The advent of the ocean-going steamship in the mid-nineteenth century marked the beginning of the end for merchant sailing ships, but it was another 70 years after Cutty Sark was built in 1869 before the last big sailing vessels finally disappeared from the world’s oceans and the trade wind routes that had served them for centuries.

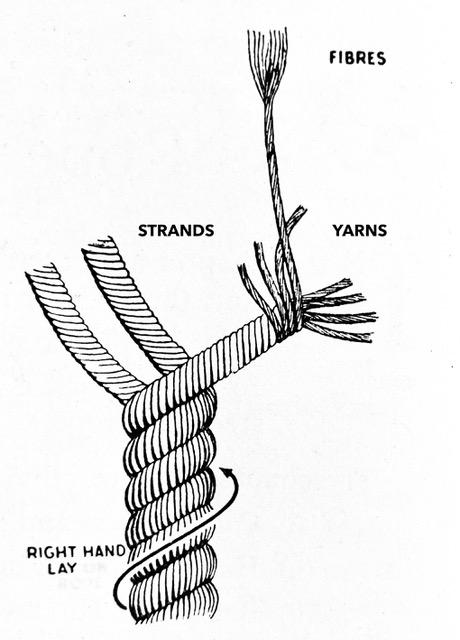

Sad as the passing of the sailing ship was, it was not the end of two natural materials that were central to its success: rope – more accurately known as cordage – and canvas, both made of plant fibres. Here, we are going to look more closely at the different fibres used to make cordage and, to start, the types of rope most commonly used in sailing ships.

This knowledge was essential for seamen, as ropes were vital for their efficiency when sailing, navigating, and handling and securing their ships in restricted waters. This is evident from the sheer quantity of cordage needed on board. There is 11 miles of rope on board Cutty Sark – more than the distance from the ship’s navigator’s eye to the horizon and back again!* Secondly, rope is essential for the safety of the ship and crew. Every rope has a breaking strain and a safe working load (SWL), depending on the material from which it is made and its size (measured by diameter or circumference).

Types of rope

Manila

A high-quality cordage for use in situations where strength is critical for safety; typically for rigging and cargo hoists. Manila is made from fibre from the leaf of the plantain or wild banana tree, grown extensively in the Philippines. When new and untreated it is a deep golden brown colour. It is flexible and stands up well to wear and weather, and so is very suitable for ship mooring lines, towing lines and ship’s boat hoists.

Sisal

Pale straw in colour and hairy, Sisal is often considered to have about 80 per cent strength of a manila rope of the same size but is less expensive. Sisal is a popular, general- purpose cordage for use where strength is not as critical for safety. This rope is made from the leaf of the agave plant, of the cactus family, which grows in Mexico, Kenya and Tanzania. New sisal rope is generally considered as strong as second-grade manila, but is not so flexible, nor as resistant to wear and weather. Because it is not as reliable as manila, sisal is not generally used for purposes where parting (or breakage) may endanger life. Sisal can be supplied tarred for weather and waterproofing. Tarred sisal is made from sisal yarns treated with Archangel or Stockholm tar and is dark brown in colour. It is heavier and not as strong as natural sisal, but it weathers better.

Hemp

Pale straw in colour, hard and smooth, this rope is obtained from the skin of a nettle-like plant grown in many parts of the world including Italy, Russia and other parts of Europe, China, the United States, New Zealand, St Helena and India. Hemp is much softer than many other rope fibres. Its quality varies greatly with the soil in which it is grown, so for some purposes in the UK its specification is divided into grades of decreasing quality (Italian, European, New Zealand and St Helena, and Indian). Italian hemp is the strongest fibre used in ropemaking; Indian hemp is not considered suitable for reliable cordage. Hemp is heavier than manila, and the best quality is stronger. Its durability is similar to manila but it is far more flexible. In sailing ships it was frequently used for rigging hoists, ship mooring lines and ship’s boat hoists. Like sisal, hemp rope can also be supplied tarred so that it weathers better.

Coir

A coconut brown colour, lightweight cordage with very rough texture. This rope is made from fibres from the husks of coconuts grown in Sri Lanka and other countries. It is very hairy and is sometimes called ‘grass line’ or ‘bass rope’. Coir rope is the weakest of all ships’ cordage but has the advantage of being so light that it floats on water. It is flexible and very springy, but soon rots if stowed away wet and does not stand up well to chafe or weather. It cannot be tarred or rot-proofed because these processes weaken it considerably. Coir rope is half the weight and has 20 per cent strength of a manila or sisal rope of equal size.

Cotton

Rope made from spun cotton fibres. It is often white but can easily be coloured with dye. Cotton rope is usually soft, flexible and comfortable to handle. It has very low tensile strength and poor resistance to water and rot. Mainly used decoratively and for crafts, it has few applications in the maritime sphere except for decorative barrier and hand ropes that take no strain.

Old rope!

Various types of discarded rope were available on sailing ships at almost any time. Although this sounds like an unpromising topic in the context of working cordage for ships, ‘old’ rope or cordage helps illustrate one of the key qualities of a good seaman – resourcefulness. Old does not equate to unusable, and seamanship is about being self-sufficient for days, weeks or even months at sea without the ready resources of a port on which to draw. Thus, old rope has many other uses to the seaman beyond its primary purpose.

At the practical end of the scale is the use of rope fibres teased out of old rope to make oakum. This fibrous material is driven into the seams between planks when caulking, or sealing, a ship’s timber hull and decks to make them watertight.

Rope fibres could also be used to make spunyarn, a type of general-purpose cord or twine made and used by seamen. This yarn was spun from old rope fibres and then tarred with Stockholm tar as a preservative. It was typically used on board for seizing (binding one rope against another), serving (tightly winding the cord around a rope to protect it) and other purposes where a twine or light cord was required. These methods can be seen on board Cutty Sark today.

Sailors with time on their hands were often adept hobbyists and craftsmen, so another use of old rope was the making of articles which were both practical and decorative. Ropework has always been in the sailor’s compendium of skills and discarded rope could nearly always find an outlet. Ships were regularly moored to quays and harbour walls and occasionally to other vessels, so what better use for old rope and a skilled seamen’s ropework than to produce stout fenders to protect the hull and bulwarks? Rope could also be used to make decorative mats for doorways and ladder feet and unlaid, or untwisted, rope strands could be worked into decorative bell ropes, handles and finials on ships’ fittings, chests, hammocks and handles. There was almost no limit to the things keen sailors could decorate.

*At an eye height of 17 ft above sea level, the horizon is 4.73 nautical miles (nm) distant, or 8,771 m.

Related facts and terms

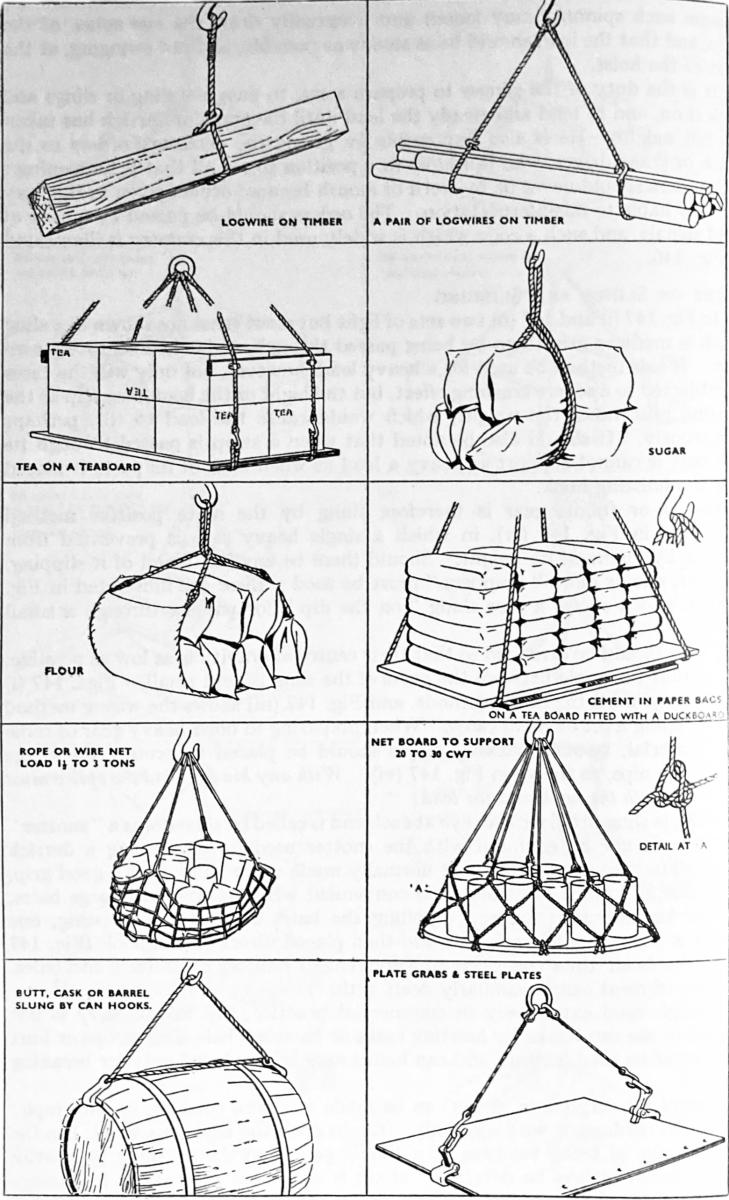

Sling (pictured): A rope used to encircle a boat (vertically), bale, or cask so that it could be hoisted.

Lifting gear: Equipment used for lifting loads, such as a ship’s cargo.

Boat falls: Lines for lowering and hoisting ships’ boats.

Tackle: Typically in ‘block and tackle’ (pictured). A single rope rove through a ‘pulley’ block, or blocks, and used to work heavy loads such as yards, sails and cargo.

To part (a rope): to break a rope: Never say a ‘break’ unless you want to be singled out as a landlubber!

Seizing (pictured): Binding two ropes tightly together in parallel to ‘stop’ one or both running, by friction. A seizing is almost always made with a smaller size of cordage than those being seized (see images).

Serving (pictured): A tight cord or spunyarn binding around a rope to prevent fraying or chafing.

Hawser: A mooring hawser is a large gauge rope used for mooring the ship to a wharf or mooring buoy.

Lay: The direction in which rope strands are turned in rope-making, either left or right-handed. To unlay a rope is to separate and untwist the strands.