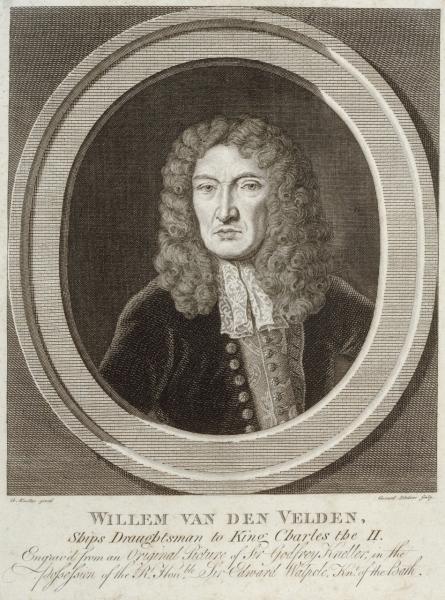

The arrival of the Van de Veldes in England transformed marine painting in Britain.

For a century after Willem van de Velde the Younger’s death in 1707, artists looked to him and his father for inspiration. Not until J.M.W. Turner did British marine painting emerge from the long shadow cast by their work.

“Turner is famously supposed to have claimed that it was a Van de Velde, specifically a print after Van de Velde, that made him a painter,” says Dr Allison Goudie, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich. “Indeed he was a proud owner of many Van de Velde drawings, some of which we have in the collection here at Greenwich.”

“Paper items are fragile; they are very sensitive to environmental changes like light, temperature and relative humidity,” adds Paper Conservation Manager Emmanuelle Largeteau. “It’s quite incredible therefore that so many drawings have survived 350 years and are now in the Museum collection. It shows that people cared for them; the drawings were preciously kept by different collectors before coming to us.”

Drawing inspiration – who collected Van de Velde drawings?

The Van de Velde studio was dispersed in 1714 following the death of Cornelis van de Velde, the son of Van de Velde the Younger. While it’s not possible to trace what happened to their vast archive of drawings, there is no doubt that the works held a great deal of interest for artists and collectors.

“We do know that over the course of the 18th century, many artists owned Van de Velde drawings,” Goudie says. “They were clearly a source of inspiration for these artist collectors – some would even trace over the original drawings.”

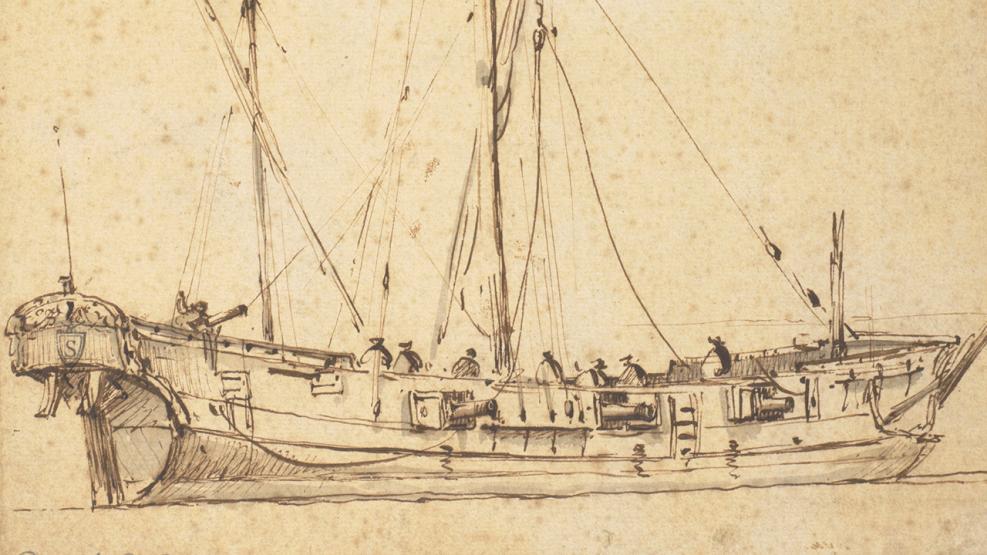

This drawing of a ship by Van de Velde the Younger features a large 'S' within a shield on the stern of the vessel. It is clear that this stamp has been added later, and is, in fact, the mark of the person who owned the drawing: 17th century artist and engraver Johann Gottfried Schumann. Use the slider to zoom in on the mark.

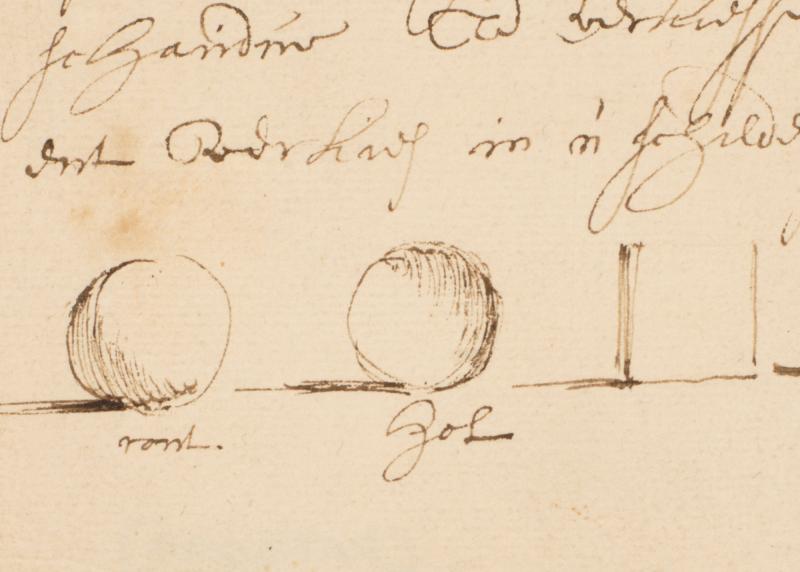

Largeteau agrees: “We can find evidence of later additions on some of the Van de Velde drawings. This was not unusual at the time, but it can be surprising for us today.

“It’s possible to identify these later interventions. You can notice, for example, the different way they trace a line, the way they hold a tool, the different pressure they apply and the different inks they use. These are just some of the ways we can identify different hands on the same drawing.”

A number of Van de Velde drawings in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection were previously owned by Turner. These bear the tell-tale signs of studio use, from a stain left by a jar to the marks of oily fingerprints.

“It’s tantalising,” says Goudie, “to wonder whether these fingerprints come from the Van de Veldes or from Turner.”

The Van de Veldes' influence today

The Van de Veldes’ arrival in Greenwich ushered in a taste for maritime art in Britain that continues to this day.

“They may not be well known today, but ‘Van de Velde’ remains a household name – literally,” according to Goudie. “Think of all those paintings of ships that you have seen in domestic or institutional interiors. Almost all of them will be, in some way, indebted to the Van de Veldes.”

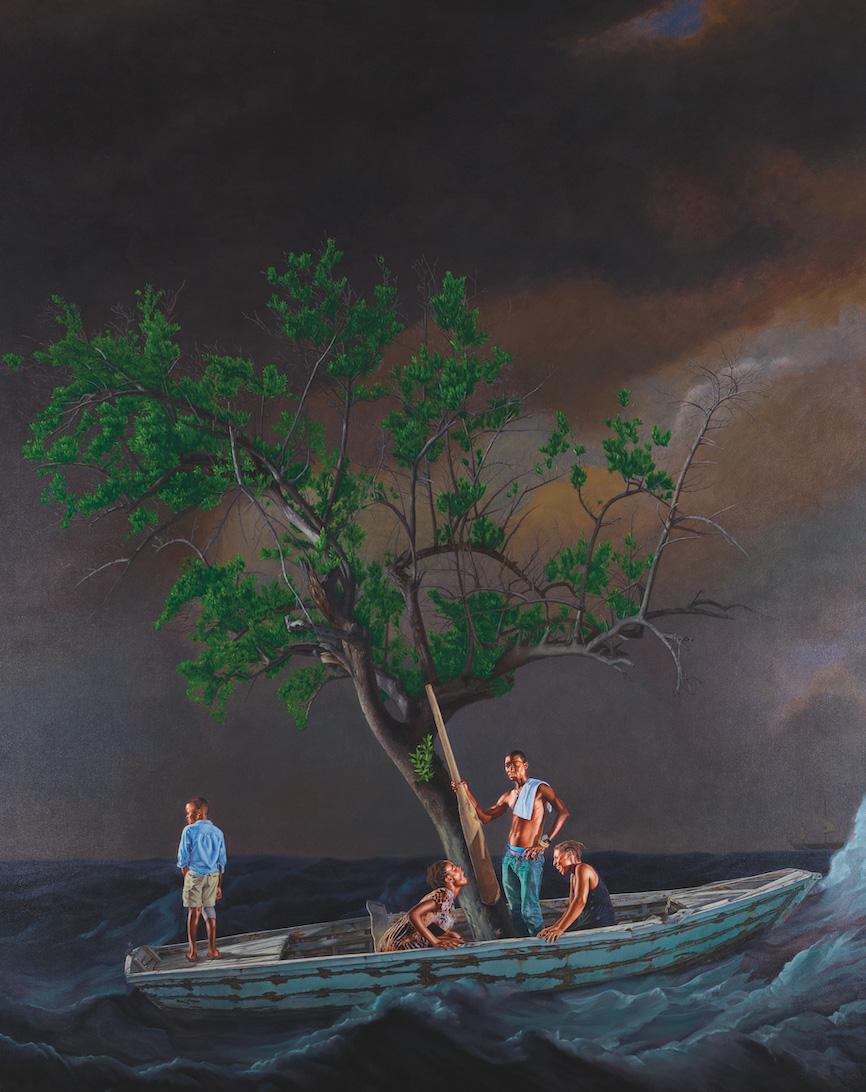

Contemporary artists too continue to engage with the traditions of marine painting. One example on display in the Queen’s House is Ship of Fools by the American artist Kehinde Wiley.

The painting is part of a series that depicts migrants from island nations. It includes the spectre of an 18th-century ship on the horizon, a reference to the histories of colonialism and slavery that often shape contemporary migration patterns.

In this context, it must be remembered that many of the Van de Veldes’ patrons made their money from enforced labour and forced migration in the East Indies and on the transatlantic trade routes. Wiley’s work reflects on how the marine painting tradition intersects with maritime imperialism.

Another work at the Queen’s House, Rear Window (Dinner) by Maisie Broadhead, is a bold reimagining of 17th-century Dutch paintings of domestic interiors, in which a shipwreck painting on the wall provided a clue for understanding the narrative unfolding in front of it.

In Broadhead’s work, a stormscape, very much like a Van de Velde painting in the collection at Royal Museums Greenwich, is visible in the background of a chaotic dinner scene. The wrecked ship echoes the upturned chairs and spilled wine, yet the precise nature of the events that have just unfolded remains elusive, inviting the viewer not only to fill in the gaps, but to reflect on traditional gender stereotypes.

Preserving the Van de Veldes’ legacy

The entire collection of drawings at Royal Museums Greenwich has been recently digitised, allowing everyone to explore the drawings online for themselves. This digital access is particularly important given the fragile nature of works on paper.

“Because these drawings are so sensitive, we need to both control the environment and limit the length of display,” explains Largeteau. “A selection will be on display for one year as part of the Van de Velde exhibition at the Queen’s House, but they will then need to ‘rest’ in the Museum stores for ten years. That way they can be protected and preserved for future generations.”

Whether in person or online, the opportunity to explore these drawings is not to be missed.

“For me as a curator what is so exciting about the Van de Velde drawings here at Royal Museums Greenwich is the insight that they give us into the workings of a 17th century artist’s studio,” says Goudie.

“That's why it’s so exciting to bring these drawings back into the Queen’s House, the very space in which so many of them were created. In the studio’s heyday it would have been absolutely overflowing with paper, a sea of drawings. Three hundred and fifty years since the Van de Veldes first moved to England, we’re absolutely thrilled to be shining a light on this unique and inspiring collection.”

Find more stories in this series

Tap the arrows to find out more about the Van de Velde drawings collection