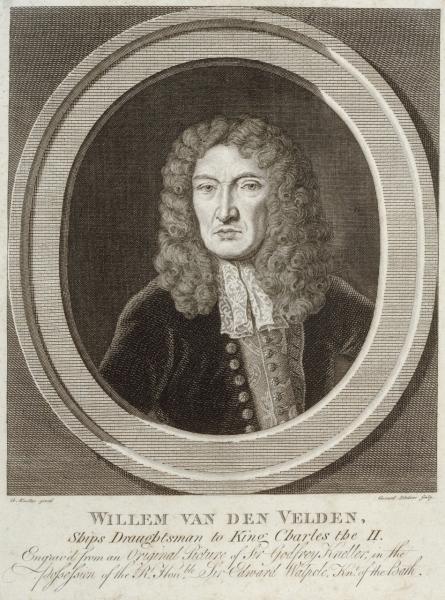

Willem van de Velde the Elder and his son Willem van de Velde the Younger were the most famous marine artists of the 17th century, renowned for their paintings of ships, stormscapes and naval battles.

Yet arguably the most important element of their creative practice were their drawings.

“Drawings were the lifeblood of their creative process, their studio practice and their success as artists,” says Dr Allison Goudie, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich.

Research into the collection at Royal Museums Greenwich is shedding fresh light on how the drawings were actually used. Far from simply preliminary sketches, these works were active tools for the Van de Veldes, repeatedly copied, referenced and reworked.

The building blocks of art

The Van de Velde studio at the Queen's House would have been overflowing with paper.

Encompassing rapid sketches, meticulous ship portraits and closely observed snapshots of maritime life, the drawings archive was vast. The collection at Royal Museums Greenwich alone includes almost 1,500 drawings by the Van de Veldes.

“This collection of drawings would have been a library of reference materials for the Van de Veldes’ paintings,” Goudie says. “If they wanted to depict a particular ship, they could go to their library of ship portraits; if they wanted to choose a particular composition, perhaps together with a patron, they would have a whole array of compositional sketches to select from.”

Taking offsets

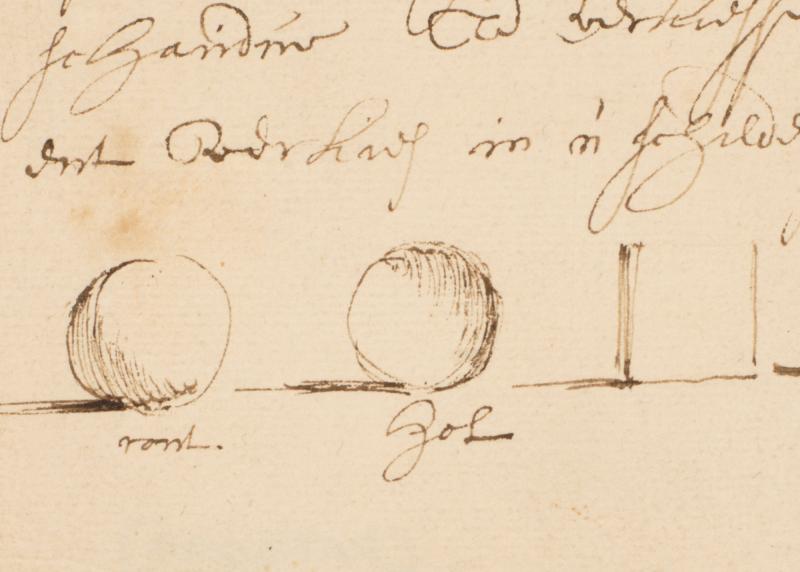

The Van de Velde drawings provide an insight into how the artists used drawing to develop their compositions, particularly their technique of taking offsets.

“The offset process was a means of reproducing a particular motif: a kind of ‘copy and paste’ for the 17th century,” Goudie says.

“It worked by taking a piece of blank paper, moistening it with water and then placing an original drawing on top of it – face down – and rubbing the back, so that the motif transferred onto the new sheet of paper.”

The technique produced a mirrored image of the original drawing.

“Some drawings which have been transferred as offsets bear the physical traces or ‘scars’ of this process, so hard have they been rubbed on the reverse,” Goudie explains.

Offsets enabled the Van de Veldes to experiment with different arrangements while keeping the same essential design. For example, they might change the position of a ship's masts and rigging, recreate the same scene under different weather conditions, or flip the orientation of a ship to better suit a given composition.

Cut and paste

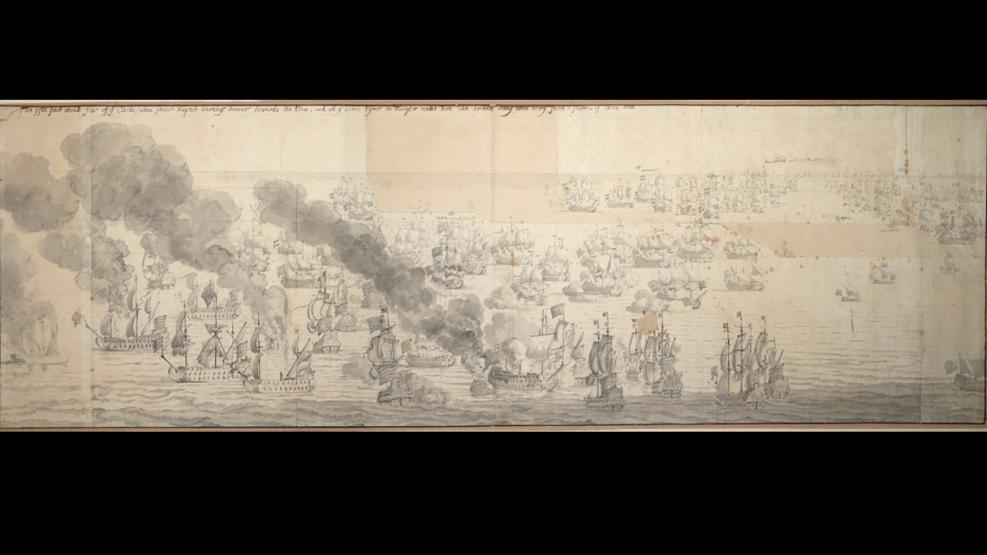

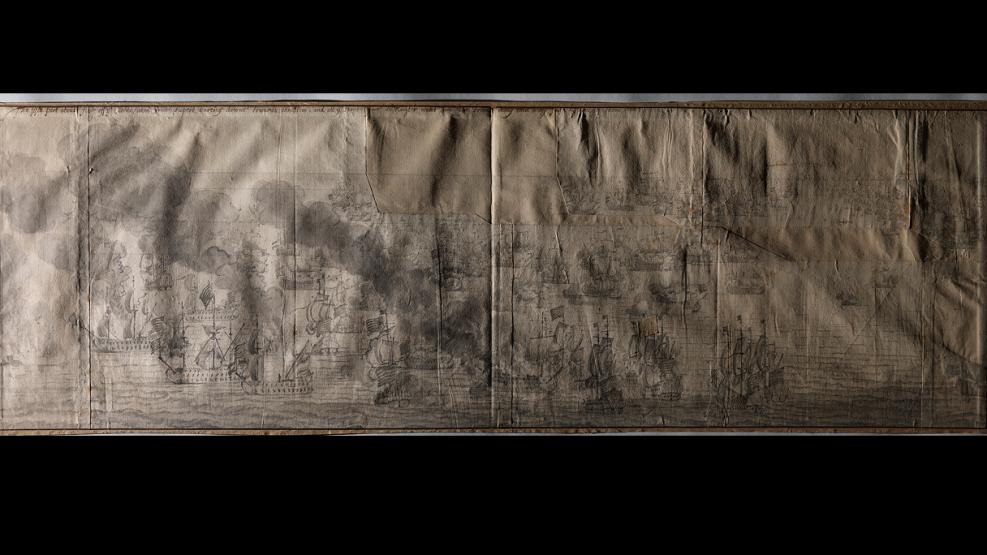

Other drawings bear witness to ‘cutting and pasting’, a technique the Van de Veldes used to reconfigure compositions.

In the drawing below by Van de Velde the Elder, the top right corner has been cut out and shifted to the right in order to widen the seascape. Two pieces of blank paper have then been added to fill the gaps left behind.

“The lines match perfectly, like a puzzle,” says Emmanuelle Largeteau, Paper Conservation Manager. “The design by the hand of Van de Velde on the inserted piece of paper attests that the enlargement of the drawing was not a later addition.”

Raking light (shining a light across the surface of a work) helps to illuminate the joins and creases in the paper. Use the slider to compare the drawing under normal and raking light.

From pencil to paint

Willem van de Velde the Younger often used his father’s drawings as a guide to produce his paintings. His painting of the Battle of Solebay relies on an earlier drawing by Van de Velde the Elder, which was created at the scene of the battle.

“Accuracy and authenticity were central to the Van de Velde studio’s unique selling proposition,” Goudie explains. But the painting also demonstrates how Van de Velde the Younger has taken creative liberties, adapting and reworking his father’s drawing to create a dramatic composition. “Ultimately, it was about an aura of accuracy and authenticity, but it was also about what made a great picture,” Goudie adds.

Use the slider to compare the drawing and the painting.

A rich archive

For Goudie, the drawings offer a valuable insight into the Van de Veldes’ artistic process, from initial sketches to detailed paintings.

“There was a whole process in between these two stages in which drawings were used endlessly to work out a composition. In the end, in fact, the painting may not be a true reflection of reality, but it’s what has worked best in a painting. The most important thing was that the Van de Veldes had a claim to accuracy, and that was centred on the Elder’s going to sea and sketching battles first hand.”

The drawings emphasise the strong working relationship between Van de Velde the Elder and Younger, and how they utilised their respective skills to benefit the studio. “The Elder and Younger had complementary talents, and both were key to the success of the studio business,” she says.

Find more stories in this series

Tap the arrows to find out more about the Van de Velde drawings collection