Conservators at Royal Museums Greenwich have been closely studying the Van de Velde drawings collection in order to better understand how to care for these fragile works of art.

"When the drawings arrive in the conservation studio, the first thing we do is a thorough examination," explains Emmanuelle Largeteau, Paper Conservation Manager.

"We want to identify the kind of paper, materials and media the artists used, as this will determine the conservation treatment we carry out."

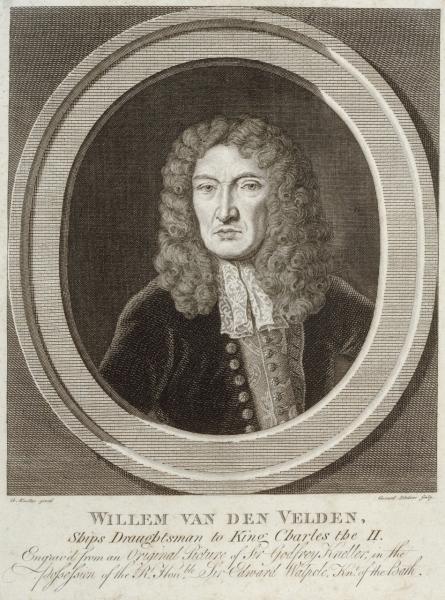

This research also helps to better understand the artists themselves, including how they sought out the best materials to support their studio practice.

"In the case of the Van de Veldes, because there is so little written archival evidence the drawings are our primary source," says Largeteau. "They take us into the artists’ studio, giving us access to the materials they used and how they worked."

Paper supplies and the Van de Veldes

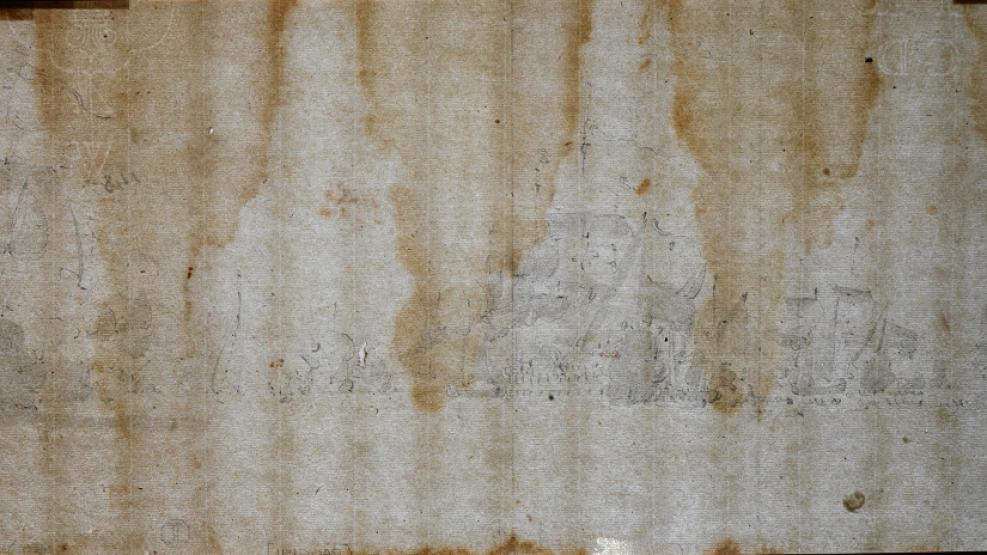

Transmitted light – shining a light through the surface of an artwork – is a helpful technique when examining works on paper, allowing conservators to identify features that would otherwise be invisible.

"Having a light beneath the drawing allows us to see evidence in the thickness of the paper and examine the watermark designs," explains Largeteau.

The graphic below shows the same drawing photographed under normal lighting conditions (left) and using transmitted light (right). Use the slider to see how transmitted light can help reveal hidden details, including the watermarks in the top corners and the vertical 'laid' lines and horizontal 'chain' lines created during the papermaking process. The regular pattern of water staining, which has occurred at some point in the drawing's life, is also more apparent.

A watermark is a subtle image or pattern set into the sheet during the papermaking process. Originally a way for papermakers to label their products, watermarks now help conservators identify where the paper might have come from and when it was made.

One interesting example in the Van de Velde collection is a drawing made on multiple sheets of paper pasted together. Each sheet features a different watermark, evidence that the papers came from multiple sources.

"One watermark was the fleur-de-lys, and another was the coat of arms of Amsterdam," says Largeteau. "These two symbols tell us that at least some of the paper the Van de Veldes used came from France and the Netherlands.”

This knowledge helps conservators build up an understanding of the material they are working to treat and preserve.

It also serves to underline how connected the Van de Veldes were with the wider European art market, bringing both artistic traditions and materials with them to England. When the Van de Veldes first arrived, most fine white and cream papers for drawing were imported from the continent, but over the course of their time in England the local industry developed and the quality of English papers improved.

Drawing media and techniques

The Van de Veldes employed various media within their drawings, with each material chosen for its particular effects and properties.

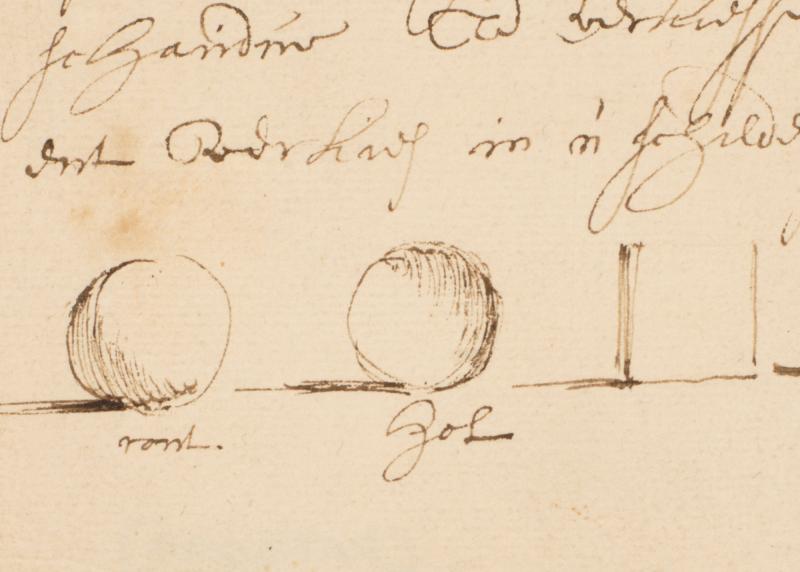

"They used a lot of graphite, which is quite unusual for 17th century artists," explains Largeteau. "However, the graphite they used wasn’t really like the pencils we know today. Instead they used raw graphite, a naturally occurring mineral. The raw material would be cut down before being inserted into a holder, making it easier for the artist to hold and draw with."

Graphite is a versatile medium, capable of producing both fine lines and broader shading depending on how it is handled. Artists can also vary the strength of the line by applying different pressure.

"Another key property of graphite, at least for the Van de Veldes, is that it is waterproof – particularly useful when drawing at sea," points out Largeteau.

"A pot of ink by contrast would be difficult to keep stable, and the artist would have to wait for it to dry before rolling up the work. Graphite is dry, waterproof and quick to sketch with."

Graphite was also well-suited to the Van de Veldes’ technique of taking ‘offsets’. This involved pressing an existing drawing face down onto a blank, moist sheet of paper and then rubbing vigorously, thereby transferring the pencil marks and allowing the artists to reproduce the same sketch multiple times.

Find out more about the offset process

As well as graphite, the Van de Veldes used two different types of ink: black ink, known as ‘carbon’ ink, and brown or ‘iron gall’ ink.

“These two types of ink were very common in the 17th century,” explains Largeteau. “We can see they used them in different ways. For instance, for thinner lines and writing the Van de Veldes used iron gall ink, while for the areas of wash covering bigger areas in the drawing, the Van de Veldes used more carbon ink.

"When iron gall ink is fresh on the paper, it looks quite black. However with age the ink turns a browner shade due to the chemical reaction of oxidation."

Shining a light on the Van de Veldes

Using ink allowed the Van de Veldes to further develop sketches originally made in graphite, allowing them to experiment with different lines, light and shadow.

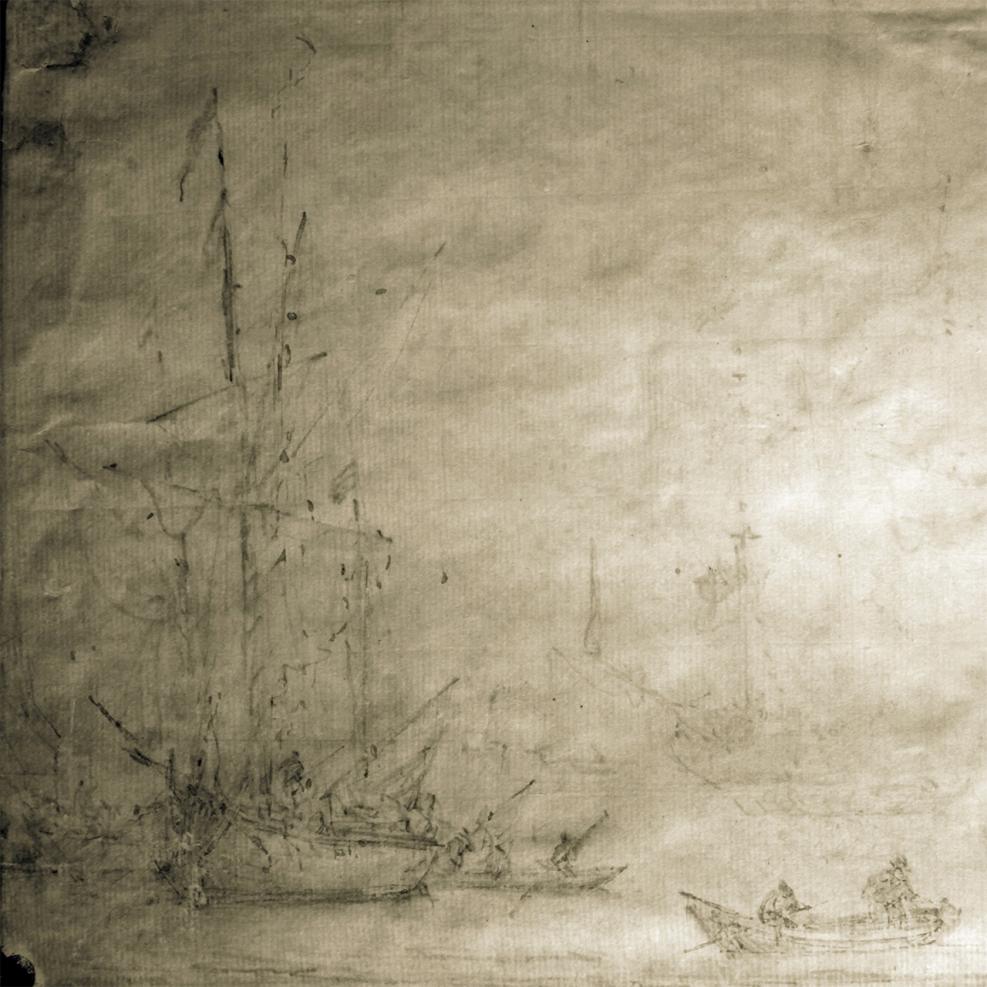

Using infrared imaging, conservators are able to see 'through' these ink layers to the pencil marks beneath.

"It allows us to gain access to the artists’ original ideas, their first sketches on the paper," says Largeteau.

In the work below for example, the position of the mast and sails has been changed in the ink version compared with the graphite underdrawing.

If you look closely, you can even see how the artist has changed the position of the figure in the centre of the sailing vessel, making them appear more hunched – the original pencil drawing has been crossed out in ink. Use the slider to compare the drawing under normal and infrared light.

Find more stories in this series

Tap the arrows to find out more about the Van de Velde drawings collection