Amsterdam, 1672: a centre of art, culture, science and trade – and a city in turmoil.

Under siege from France and England, the key region of the Dutch Republic was in the grip of an economic crisis.

King Charles II, restored to the English throne and sensing an opportunity, issued an invitation to Dutch citizens to settle and work in England. A number of Dutch artists took advantage of the offer, bringing with them their skills, trade and creativity.

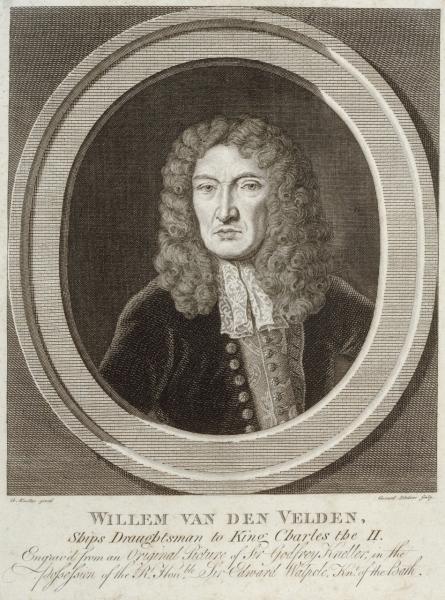

Among them were two famed marine artists, Willem van de Velde the Elder and his son Willem van de Velde the Younger.

Charles II took a particular interest in the father-son duo, offering them an annual salary and a studio space at the Queen’s House in Greenwich.

Discover how the Van de Veldes transformed the country’s cultural landscape – and why Greenwich became the birthplace of English marine art.

An emerging art scene

When the Van de Veldes arrived in England in the winter of 1672/1673, the country’s art scene was in its infancy. This was in stark contrast to Amsterdam, the art market capital of Europe, where the Van de Veldes had established a thriving studio business.

“Charles II saw in this situation – the so-called 'Disaster Year' of the Dutch Republic – an opportunity to bring over Dutch talent to help establish and grow various industries,” explains Dr Allison Goudie, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich. “The Van de Veldes, like many artists, sought new opportunities in England.”

The Van de Veldes were regarded as the leading marine artists of their day. Greenwich, with its riverside setting and easy access to the royal dockyards at Deptford, Woolwich and Chatham, was the ideal location for them.

“Greenwich was a site of constant maritime activity with ships and all sorts of different craft coming and going,” Goudie says. “This was hugely important to the Van de Veldes because it provided an endless amount of inspiration for their compositions. The proximity to the royal dockyards was also very important, of course, giving the Van de Veldes direct access to the ships of the Royal Navy, where they could make intricate drawings – known as ship portraits – of these vessels, which would then be incorporated into their paintings.”

The Queen’s House: an architectural masterpiece

Greenwich was an important cultural as well as maritime centre.

The Queen’s House, where the Van de Veldes were provided with their studio, was a revolutionary addition to the area’s skyline.

“When it was completed in the 1630s, it was absolutely cutting edge. It would have looked to 17th-century eyes much like the glass and steel skyscrapers that we see across the river now from Greenwich,” Goudie says. “Such was the contrast of this gleaming white, geometric building in the Classical style – the very first such building to be designed in Britain – to the higgledy-piggledy, ramshackle red brick Tudor palace into which it was inserted.”

By the time the Van de Veldes arrived in Greenwich in the 1670s, the Queen's House was no longer a working royal residence. Instead it was a grace-and-favour mansion, and a bustling intellectual hub.

“The Queen’s House that the Van de Veldes knew would have been a melting pot of the arts and sciences,” Goudie explains.

Occupants included John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal, who took observations from the Queen’s House while the Royal Observatory was being constructed, and Sir John Chardin, a French Huguenot jeweller.

Inside the Van de Velde studio

The Van de Veldes’ studio was situated on the ground floor of the Queen’s House overlooking Greenwich Park.

This south-facing aspect, Goudie says, was unusual for an artist studio: “The preference was always for a north-facing studio, because the light coming from the north was more consistent over the course of the day.”

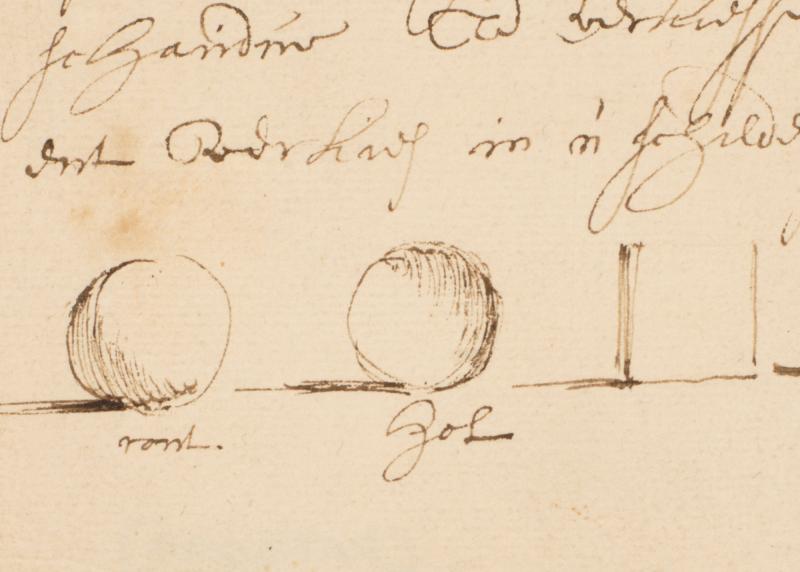

The Van de Veldes each received a royal salary of £100 a year to create drawings and paintings of ‘Sea Fights’. Overflowing with paper, the studio would have been filled with detailed drawings made by Van de Velde the Elder, as well as Van de Velde the Younger’s paintings of stormscapes and shipwrecks.

While little archival information is available about the day-to-day operation and configuration of the studio, it is likely that it was a family affair.

Cornelis van de Velde and Johann van der Hagen, Van de Velde the Younger’s son and son-in-law respectively, both worked as painters in the studio. Several women, including Van de Velde the Younger’s daughters, were also involved; however, it’s uncertain what their specific roles were.

The impact of the Van de Veldes

The Van de Veldes’ dramatic depictions of naval scenes and events established a taste for marine painting in England. For Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York (later James II), the artists also played a crucial role in showcasing English naval power.

While royal commissions formed a key part of the Van de Veldes’ work at the Queen’s House, the father-son duo were also shrewd entrepreneurs. The Van de Veldes utilised their vast catalogue of sketches and drawings to capitalise on London’s flourishing art market.

The Van de Veldes’ royal patronage came to an end following the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 and the deposition of James II, and the pair left Greenwich for Westminster. However, the Van de Veldes’ legacy continued to inspire generations of artists, many of whom are now represented in the collections of Royal Museums Greenwich.

“By the time of the Van de Veldes’ deaths, London had established a thriving art market of its own,” Goudie says. Around the year 1690, some 200 works attributed to the Van de Veldes were available at auction in London. “It demonstrates their significance in the English art scene – and the sheer demand for their work.”

Find more stories in this series

Tap the arrows to find out more about the Van de Velde drawings collection