The successful location and exploration of a number of shipwrecks in the last 10 years has challenged some of our assumptions or received wisdom about events and people.

This highlights the importance of combining archaeology and history to try to get as close to the truth as possible in order to improve our understanding of our own past.

Prompted by the discovery of the wreck of HMS Gloucester, a Third Rate, two-decker, launched in 1654, and the potential for new insights into the lives of those on board, Jeremy Michell, Senior Curator of Maritime Technologies, looks at a few shipwrecks whose discovery has begun to change the way we understand their contexts.

HMS Gloucester (1654)

The Gloucester was wrecked on the Lemon & Ower sandbanks off Great Yarmouth on 6 May 1682.

On board were not only the usual complement of crew and officers, but also James, Duke of York (later James II & VII) and his entourage. James (pictured) was on his way to Scotland to collect his pregnant wife Mary of Modena to bring her back to London.

Events surrounding the loss of the ship are a tangle of confusion and blame, with an estimated loss of life between 130 and 200 people.

Locating HMS Gloucester in 2007 (only announced in 2022 in order to protect the wreck), provides maritime and social historians with an unprecedented opportunity to understand life on board a warship that is a unique microcosm of Stuart society.

Finds from the wreck include personal items such as a pair of glasses, clothes, shoes, clay pipes, spoons, and sealed glass wine bottles. Also recovered were cannon and the ship’s bell.

The ship seems to have split down the keel, leaving half of it to be buried in the shifting sands and preserved. These remains will be important for us to understand how 17th Century warships were built and repaired at a time when this technical knowledge was not always recorded.

The exploration ship Endurance (1912)

In March this year the news of the discovery of Shackleton’s exploration ship Endurance was announced. Finding the wreck in the Weddell Sea off Antarctica was a remarkable piece of planning and good fortune (for weather and ice conditions). The photographs and film footage recorded the ship upright on the seabed in an amazing state of preservation.

Shackleton purchased Endurance for his 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, where he hoped to the first person to cross the Antarctic continent via the South Pole. However, the Endurance was trapped in the Weddell Sea for months, finally being crushed by the ice and sinking.

The evocative footage and photographs by Frank Hurley, supported by the accounts of the ship’s last days suggested the complete crushing of the lower hull by the moving ice floes. However, the expedition that found the ship has shown otherwise.

The wreck of the Endurance has revealed that the ice punctured the hull, letting water flow into the hold. The floe also seems to have moved across the upper deck, removing much of the additional structures above the deckhouses. Yet, the evidence now indicates that the ship sank in one piece, suggesting that the ice floes parted long enough for the water-logged ship to slip beneath the ice and settle on the sea bed.

Not only does it give us a better understanding of the ship’s last moments, but ongoing analysis of the footage and survey results will help bring the story of the Endurance to a new audience, especially where it also records the personal items that have been located.

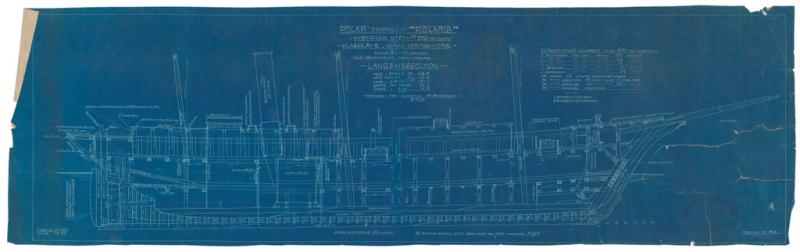

The survey work may also help us understand how the ship was built to withstand polar ice, and then modified to accommodate Shackleton’s expedition – he avoids a description in his popular account.

HMS Erebus & HMS Terror

The two wrecks that have had the most significant impact on our understanding of a maritime disaster are the exploration ships Erebus and Terror.

These ships left England in May 1845 to complete the surveying of the Northwest Passage and undertake scientific research, led by Sir John Franklin. However, from 1848, with no news of their reappearance, the Admiralty sent out a large number of search expeditions to look for them.

While relics were located in 1850 and again in 1853 and 1859, there was no clear sense of what had happened to the crews and the ships. Inuit oral testimony recorded that at least one of the ship was reoccupied and a ship had sunk off Adelaide Peninsula.

However, the veracity of these stories was not appreciated until more recently as researchers using the oral testimony showed that they could be relied on to interpret the final stages of the catastrophe.

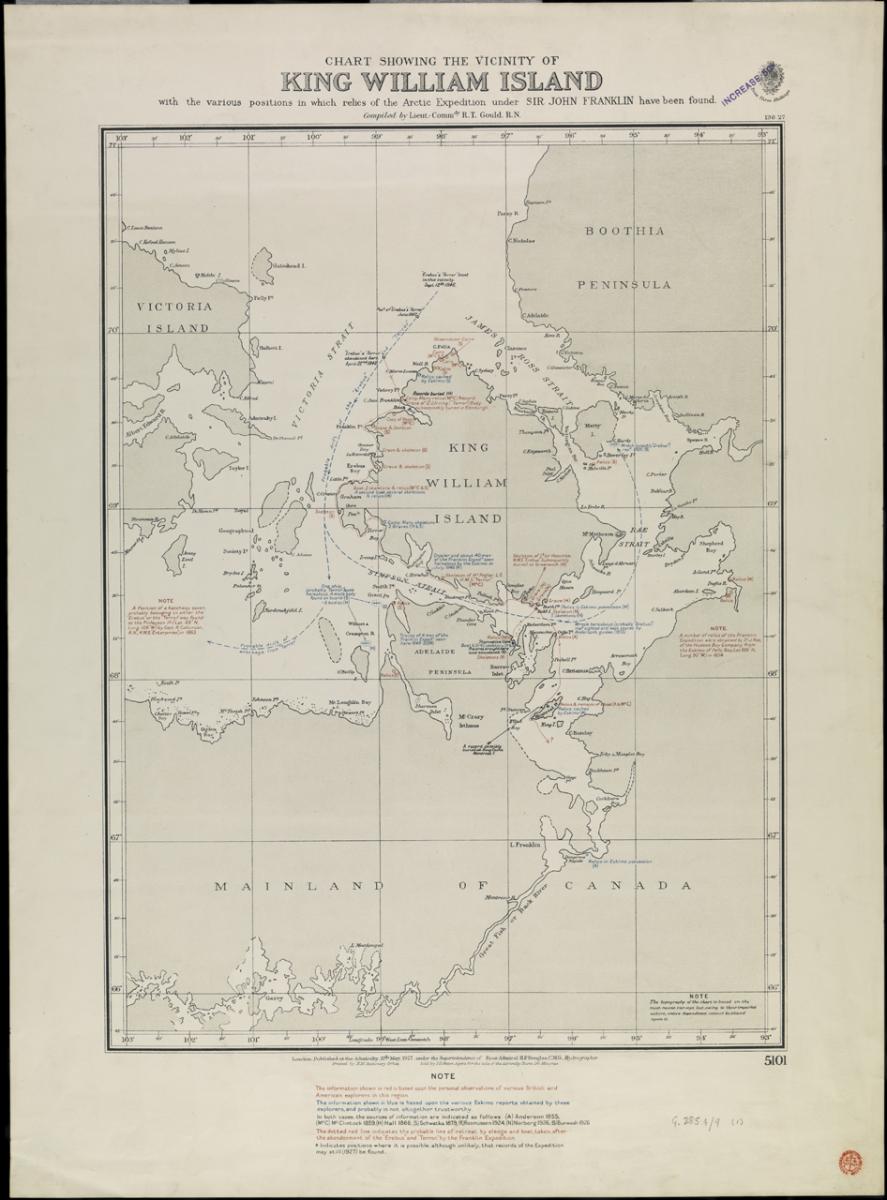

Search expeditions in the 20th and early 21st Centuries had surveyed the last known area where the ships were abandoned and potential drift patterns – taken from the only surviving message by Captains Crozier and Fitzjames in 1848.

A chart from 1927 by R. T. Gould (pictured) indicates a number of potential locations for the two ships based on the known currents, reports by British and American expeditions and Inuit reports. However, it took a concerted effort by Parks Canada with assistance from other government departments to look methodically for the ships.

The location of Erebus in Wilmot & Crampton Bay corresponds with material found in 1880 by Lt. Schwatka on his expedition, as well as coinciding with Inuit testimony that a boat sank in the area.

However, the location of HMS Terror, coincidentally in Terror Bay on the southwest side of King William Island, raises interesting questions about how it got there. As surveying, filming and excavation work continues on the site, it will tell us more about whether the ship was re-occupied and how it was abandoned by the remaining crew. It may tell us about whether the ship was sailed to its present location – which is not far-fetched, as there is evidence of a large camp on the shore of the bay.

New perspectives

What these wrecks are showing us is the importance of combining the written record and material culture with the evidence that these ships provide. The wrecks are all time-capsules of the moment they sank, storing within them personal objects that can tell us about the people on board and the society they lived in.

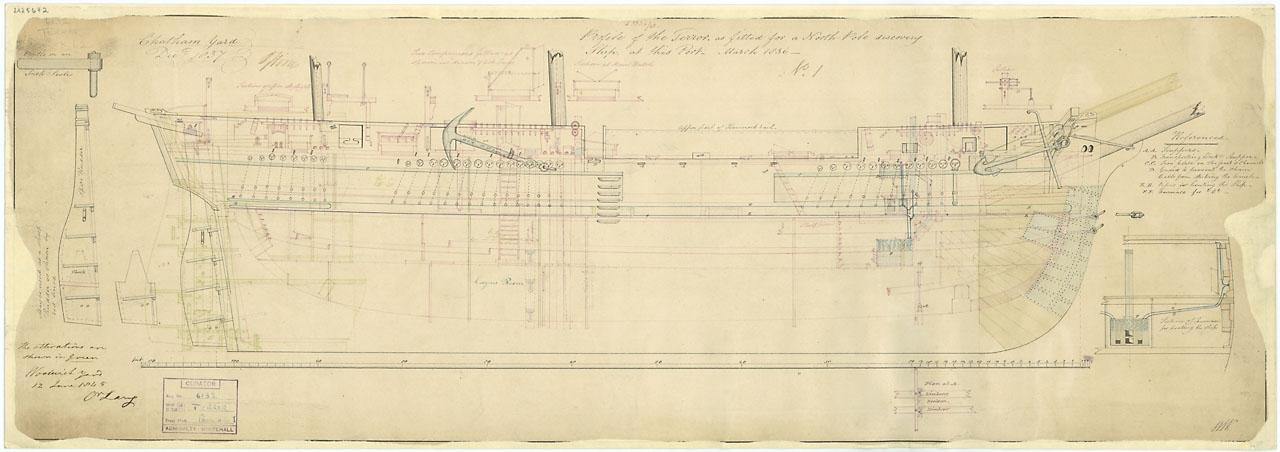

Moreover, investigating the ships will improve our understanding of how ships were built, repaired and why they sank, on occasions linking across to the ship plans collection that we hold at the Museum.