Since its foundation in 1616, the Queen’s House has been a space for female creativity and artistic expression.

The building was the vision of Queen Anne of Denmark. A keen patron of the arts, Anne commissioned architect Inigo Jones to create a garden retreat for her cultural activities.

Under Queen Henrietta Maria, the Queen’s House was transformed into a ‘House of Delights’ showcasing the leading creatives of the age, including ceilings once painted by Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter, Artemisia.

Now an acclaimed art gallery, the Queen’s House continues to champion ingenuity and innovation. It contains a range of art by trailblazing women artists, from paintings and textiles to sculpture and photography.

Discover more about some of the works by women artists on display with Royal Museums Greenwich’s art curators. The Queen's House is free to visit and open daily from 10am-5pm.

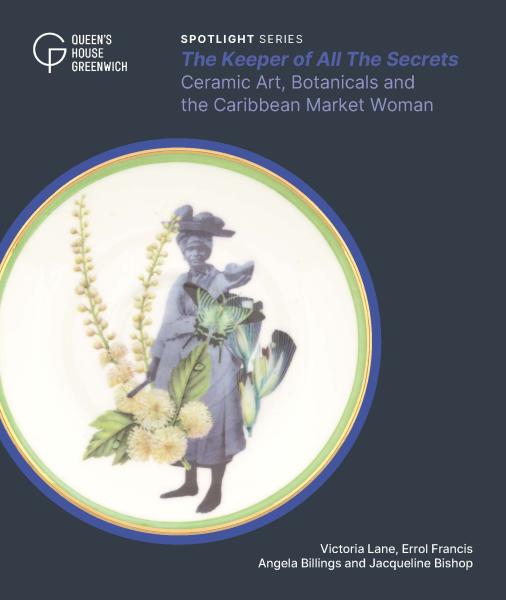

The Keeper of All The Secrets by Jacqueline Bishop

Jacqueline Bishop (born 1971) is an artist, a writer, poet and scholar, based in Jamaica and the USA. Her practice is focussed on Black female agency. Royal Museums Greenwich has recently acquired one of her ceramic works, The Keeper of All The Secrets (2023), which takes the form of a traditional British tea service.

It explores the significance of the Caribbean 'market woman', a role that both Bishop’s grandmother and great-grandmother undertook in Jamaica. The tea service is adorned with the artist’s collages of Caribbean market women intertwined with local flowers and plants.

Since the time of enslavement the market woman has been central to the community as a healer and a trader, preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge – but her role has been critically overlooked.

Victoria Lane, Senior Curator of Art and Identity

Supported by Cockayne Grants for the Arts, a Donor Advised Fund, held at The Prism Charitable Trust.

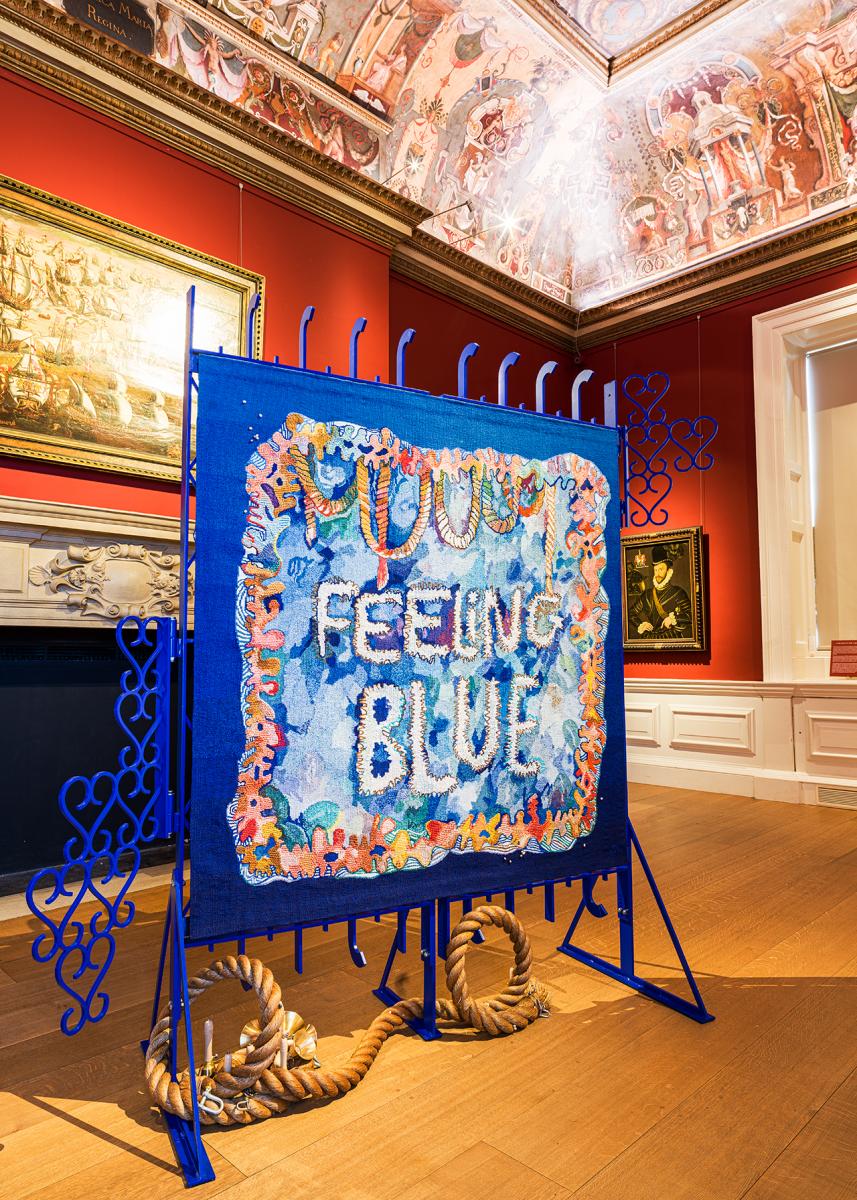

Feeling Blue by Alberta Whittle and Dovecot Studios

Alberta Whittle (born 1980) is a Barbadian-Scottish artist, researcher and curator. As an artist, she works across different media and has produced films, prints, sculpture and performance. Her practice recognises and explores the legacies of colonialism and anti-Blackness and the harm they do today, but also seeks to create spaces for conversation, collective care and healing around these issues.

In 2022, Royal Museums Greenwich commissioned Whittle to design a tapestry installation for the Queen’s House, in collaboration with Dovecot Studios. The resulting work, titled Feeling Blue, is a celebration of African-Caribbean culture. It references Blues music, Barbadian Chattel House architecture and spiritual resistance within the African diaspora, such as the Akan symbol of Sankofa, seen in the heart-shaped details in the gate structure.

It also explores environmental exploitation and what Whittle calls 'the accumulated grief of empire' through language, colour and its construction and display.

Maya Wassell Smith, Assistant Curator of Art

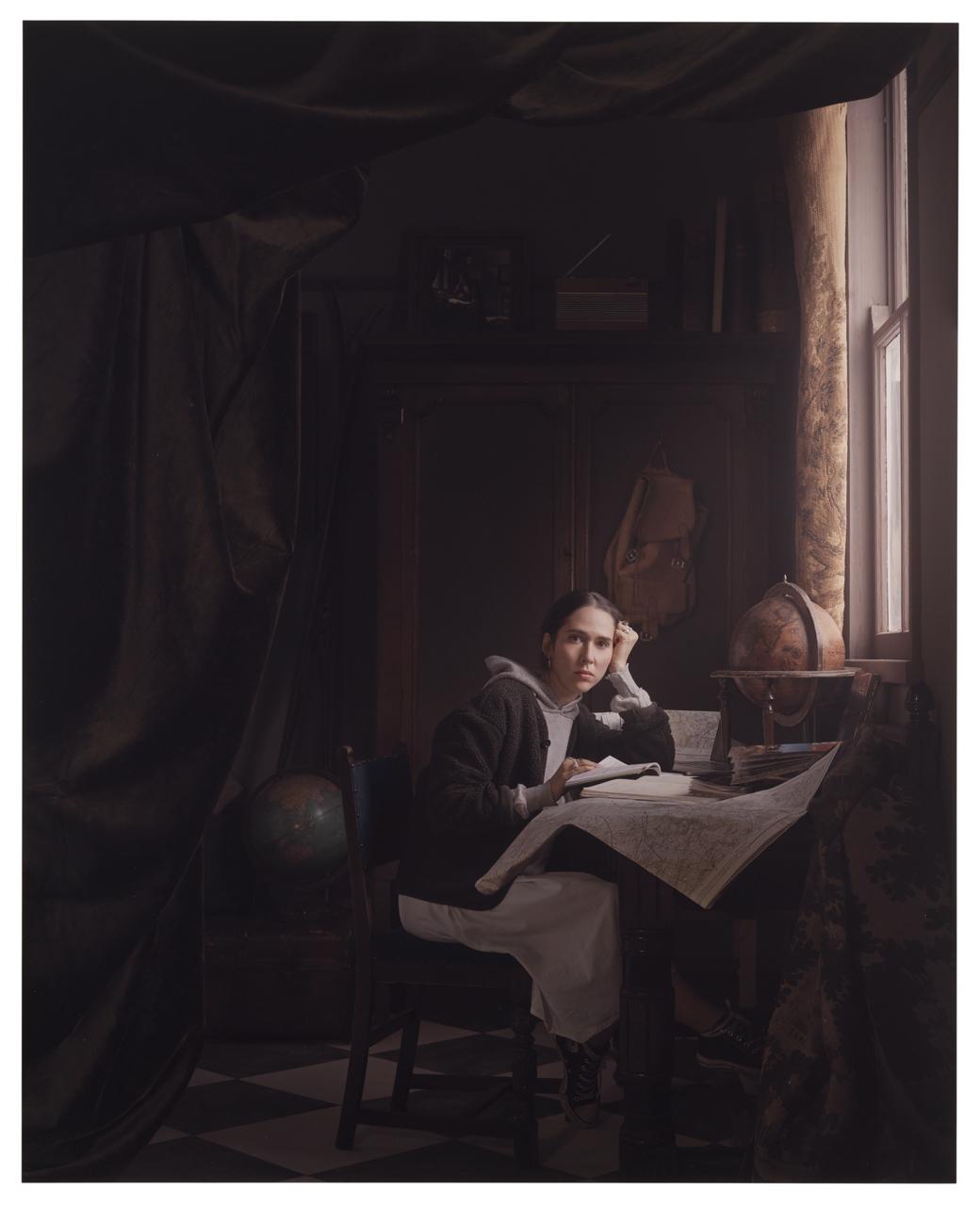

Artist Sitting and Explorer by Maisie Maud Broadhead

Royal Museums Greenwich recently acquired two photographs by the London-based artist Maisie Maud Broadhead (born 1980). In her work, she draws on conventions of Old Master painting to explore alternative histories, especially as they relate to gender.

In Artist Sitting (left), a young 21st-century woman is pictured in a pose and costume that echoes Vermeer’s Girl Interrupted at Her Music (seen in the background of the photograph). The interior is reminiscent of a 17th-century artist’s studio, echoing paintings like one by Michiel van Musscher, which was previously thought to depict Willem van de Velde the Younger.

Broadhead’s photograph now hangs in a room that was once used by the Van de Velde family as part of their workshop. Though women played a crucial role in the day-to-day administration of artists’ workshop businesses, we often have few details of their lives beyond how they were related to their more famous male relatives. At least one of the Younger’s daughters, possibly Maria or Judick, was an accomplished painter, but no paintings attributed to her survive.

In Explorer (right), Broadhead echoes Vermeer’s paintings The Geographer (seen in the background of Broadhead’s photograph) and The Astronomer, replacing their 17th-century male subjects with a 21st-century female one.

The sitter is surrounded by an array of astronomical and scientific instruments, maps and charts. Though science and mathematics were not traditionally regarded as appropriate subjects for women and girls, it is also thanks to women – such as Margaret Flamsteed (née Cooke) and Margaret Bryan – that astronomy flourished in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Now on display in the Queen’s House, Broadhead’s works help us reflect on how the history of Greenwich might have differed had women like Maria and Judick van de Velde or Margaret Flamsteed had the same freedoms from domestic duties as their more famous male relatives.

Vittoria Cervini, Assistant Curator of Art

Sea Mark by Tania Kovats

Tania Kovats (born 1966) is a renowned British artist whose practice and research encompasses sculpture, installation, drawing and writing. Her work explores our experience and understanding of landscape through our relationship to water, increasingly with a focus on environmental issues around our oceans.

Sea Mark (2014) is a large seascape made from handmade ceramic tiles glazed with cobalt blue painted brush strokes. It immerses the viewer in the broken motion of the surfaces of the sea, receding into a remote horizon. In 2022 Kovats spoke of her inspiration for the ongoing Sea Mark series, suggesting that "at this time in our collective history, our island status is more important than ever in how we see ourselves."

Kovats exhibits internationally, publishes regularly and her work is held in several major collections. She is currently Professor of Teaching and Research at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design.

Victoria Lane, Senior Curator of Art and Identity

Discover more great art

Sign up to the art newsletter for more information about Royal Museums Greenwich's art collection, and learn about upcoming exhibitions and events.

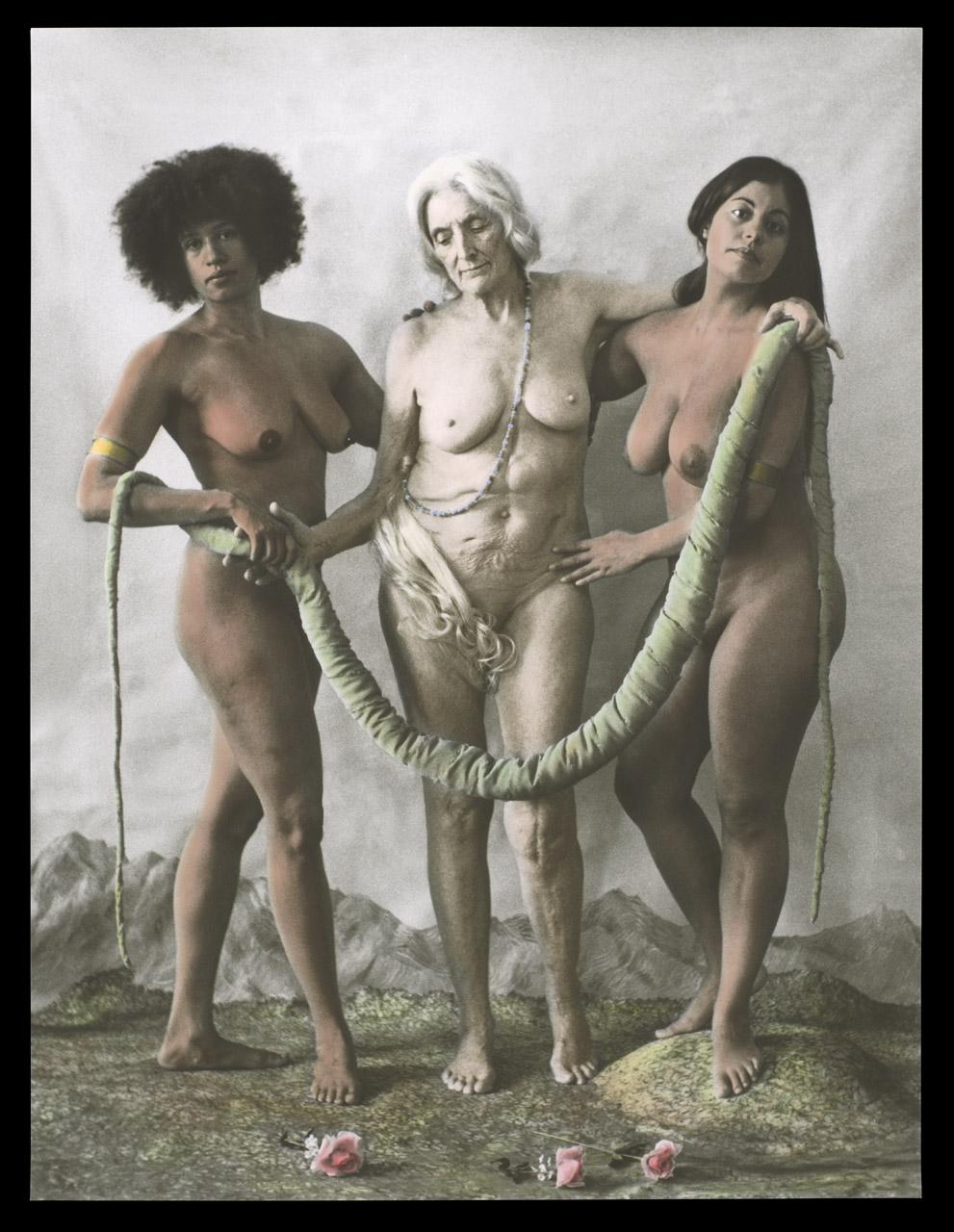

Kingdom of this World: Triptych by Leah Gordon

This trio of photographic prints explore the entwined histories of enslavement, rebellion, class struggle, industrialism and seafaring. All three images are based on historic engravings.

The central image (pictured) is an allegory of the relationship between Europe, Africa and North and South America, referencing a book illustration produced by William Blake in 1796. The other two are based on John Thomas Smith’s portrait of Black sailor-turned-street performer Joseph Johnson from 1815.

An artist and curator from north-west England, Leah Gordon (born 1959) was inspired to create this piece by Cuban author Alejo Carpentier’s 1949 novel, Kingdom of this World. The book follows the story of the Haitian Revolution, a successful uprising of enslaved people against French colonial rule in 1791.

Gordon’s photographs draw parallels between events in Haiti and developments in other parts of the world.

Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art

Cut paper picture c.1806, by an unknown female maker

This paper-cut picture commemorates Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson and is made from blue paper with small pieces of red and white paper attached with glue.

It was almost certainly made by a woman. Making silhouettes and paper-cuts was extremely popular as a creative endeavour among middle and upper-class women in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Some women paper-cutters became well-known, but most were only celebrated among their friends. Paper-cutting was a social activity that women practised together, trading materials and techniques, and often exchanging finished pieces as gifts.

There is some evidence that the artist of this piece was connected to the novelist Lady Sydney Morgan (née Owenson), but we don’t know whether she made it or whether it was made by a friend and presented to her. Like many of the objects in our decorative art collections, the work of this creative and skilful woman is not recognised by having her name recorded.

Maya Wassell Smith, Assistant Curator of Art

‘Chippy’ – the carpenter on HMS ‘Curacoa’ by Rosemary Rutherford

Rosemary Rutherford (1912–1972) created this watercolour portrait while working as a volunteer nurse in the temporary naval hospital established at Cholmondeley Castle, Cheshire, during the Second World War.

The hospital specialised in treating people experiencing mental health difficulties. The carpenter’s careworn expression is a reminder of the psychological impact of conflict.

Having trained as an artist at the Slade School before the war, Rutherford received money from the War Artists’ Advisory Committee to produce artworks depicting her fellow medical staff and their patients. She worked at several different naval hospitals and her evocative drawings record many aspects of wartime life, from air raids to surgical operations, as well as moments of relaxation and light relief.

Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art

Bust of George VI by Kathleen Scott

Sculptor Kathleen Scott (1878–1947) shows an informal side of George VI in this bronze bust, depicting the King without any royal regalia in a V-neck jumper and open-necked shirt. The work exemplifies the humanity and vulnerability that she often brought to her sculptures of male subjects.

After studying in London and Paris, Scott created sculptural models to guide pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies when he operated on servicemen injured in the First World War. After the war, she enjoyed a successful career producing portrait busts and public memorials. Yet her reputation is also bound up with her experience of personal tragedy. Among her most well-known sculptures is a tribute to her first husband, Robert Falcon Scott, who perished in the Antarctic in March 1912.

Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art

Olaudah Equiano – African, slave, author, abolitionist by Christy Symington

Christy Symington (born 1962) is Head of Sculpture at The Art Academy London. From 1996 Symington studied traditional figure sculpture and life drawing in Paris and then studied in New York, returning to London for postgraduate study at Byam Shaw School of Art (now Central Saint Martins). Her work champions the achievements of overlooked historical figures.

Made in 2006, Olaudah Equiano – African, slave, author, abolitionist tells the story of the 18th-century abolitionist's life and legacy. Born into what is now south-eastern Nigeria, Equiano was sold into slavery around the age of 11. He documented his experiences in his autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, one of the first books in Europe by a Black African writer.

His role as an abolitionist is referenced in the chains and shackles that wind around the back of the sculpture. Details of the ‘Brookes’ slave ship diagram – an image that represents how enslaved people were crammed into ships that crossed the Middle Passage – can be seen around the sides of the work. The shape that forms the back of Equiano's shoulders implies the continent of Africa.

Artemisia Gentileschi and the Great Hall ceiling

Now at Marlborough House

Artemisia (1593– 1654 or after) would have known the Queen’s House well, having, it is believed, helped her father Orazio Gentileschi complete the paintings which originally adorned the ceiling of the Great Hall.

These paintings, made up of a large central circular canvas flanked by eight smaller canvases, were intended to celebrate the flourishing of the arts under the reign of King Charles I and Henrietta Maria. All 26 figures depicted in the ceiling, except possibly one, are female – particularly apt for a queen’s residence.

The paintings were removed in the early eighteenth century for installation in Marlborough House on Pall Mall in Westminster, which Sarah Churchill, Queen Anne’s ‘favourite’, was having built at the time. They remain there today, but were cut down from their original size to fit their new setting.

At least one other painting by Artemisia, illustrating the story of Tarquin and Lucretia, now lost, hung at Greenwich during Henrietta Maria’s time – if not in the Queen’s House itself, then certainly within the broader Greenwich Palace complex.

Vittoria Cervini, Assistant Curator of Art