Pirates have long captured our cultural imagination. Adventurers and rogues, radicals and outcasts: for many people, pirates offer the glimpse of a life outside of society’s rigid boundaries.

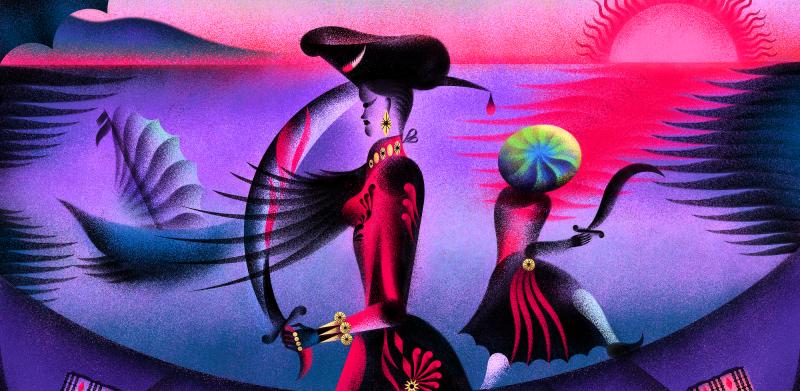

That vision of a pirate’s life has proved particularly powerful for some LGBTQ+ communities. Queering Piracy, now on display as part of a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, aims to explore the connections between pirate history and LGBTQ+ experiences.

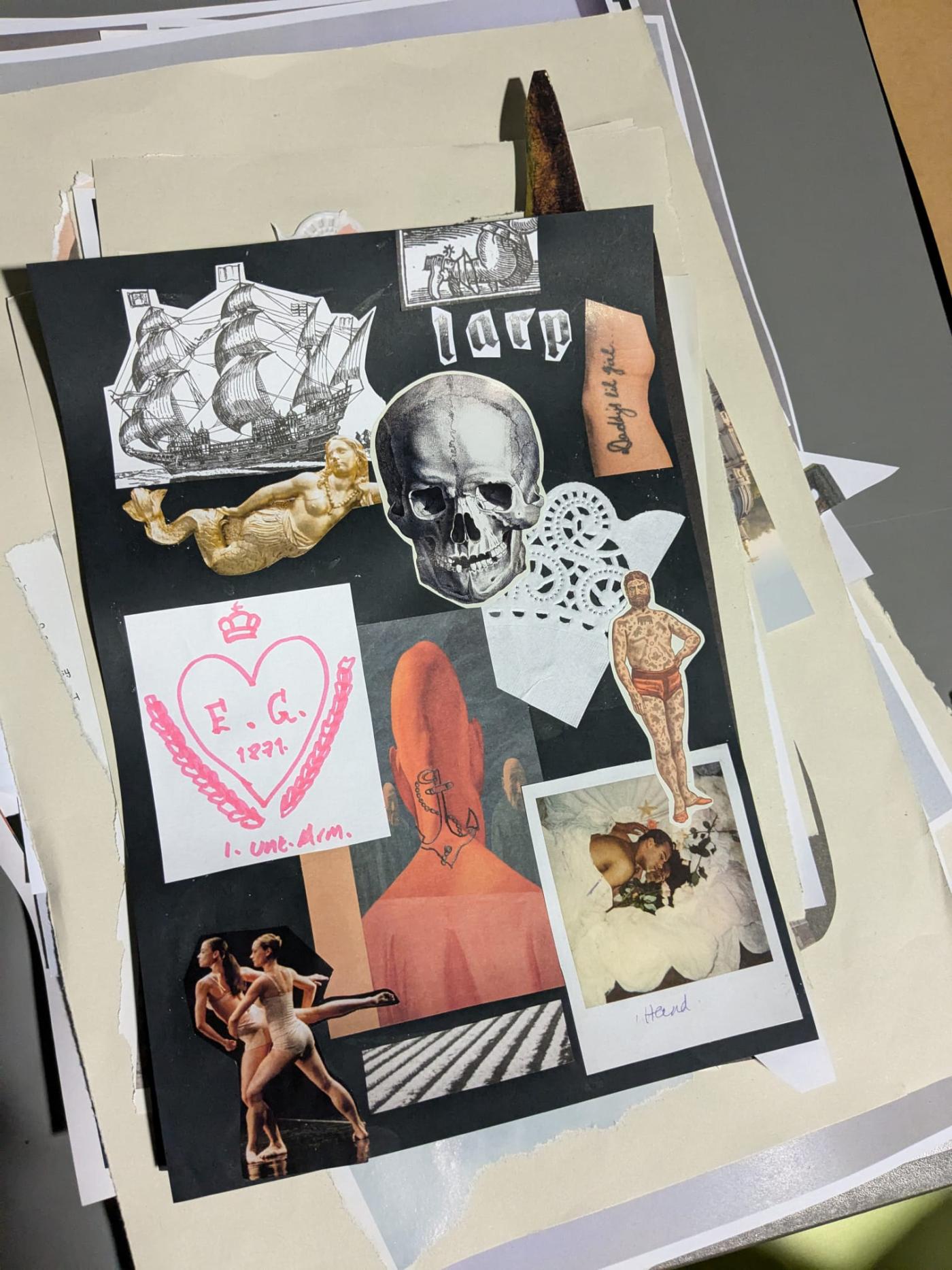

The artwork features two prosthetic torsos, merged and displayed atop a specially constructed metal frame. The arms are stretched out to either side, and the body is covered with intricately embroidered tattoos in a variety of colours.

Threaded with meaning and laced with coded references, Queering Piracy is the result of a collaboration between artist E.M. Parry and members of the Royal Museums Greenwich’s Queer History Club.

Learn more about how the work came together, and unpick the history and iconography of pirates with Parry and the Queer History Club.

What was it about pirates that first inspired this project?

Parry: I suppose the aspect that we felt most inspired by was this idea of people building communities outside of societal norms. Pirates created their own communities and rules for living – and in the process crafted identities that were able to exist outside of the frameworks generally made available to us.

That idea of ‘crafting’ identity is mirrored in how the piece itself came together. Queering Piracy emerged from a communal crafting project; while it’s my concept, it’s everyone’s work. All of the tattoos you see were created collaboratively with members of the Queer History Club. This piece thinks about gender and sexual identity as a process rather than a thing: a crafting project we can all participate in.

How did the designs come together?

Parry: It was a very conversational process, with different people sharing knowledge, ideas and inspiration, drawing on pirate history, queer history and contemporary queer experience. We first created this amazing set of collages; these were then traced to act as guides for the tattoos.

People didn’t necessarily trace their own work. Your initial idea might become someone else’s drawing, which would then be translated again as someone else stitched the picture. It became such an overlapping, multi-authored piece.

Jas: When we were choosing which pieces to put on there was definitely a little ‘polite’ competition!

Tell us about what pirates mean to you as a group.

Linnea: During one early session we talked a lot about childhood obsessions with pirate stories – including childhood crushes on Captain Hook…

Jas: …or the reaction from a certain age group to seeing Elizabeth Swann in drag in Pirates of the Caribbean 2.

Linnea: I had a big Treasure Island phase in my teens.

Jas: And then some of us had really big Black Sails phases, which is just a modern retelling of Treasure Island.

Phil: For some of us though it was more about piracy as a concept. I’m from Poland: I could not really relate to those cultural references, but piracy still felt like it had always been a part of my life. As a kid you learn ‘anarchy’ quite early on: fighting for resources, fighting to be included. In a way piracy is what I’ve been doing since I was young.

Linnea: We also highlighted the idea of ‘video piracy’. If you grew up burning CDs and finding things on sketchy websites, piracy doesn’t exactly scream murderous criminality in the way it would have to people in the past.

Jas: I spent an extensive period of my childhood wearing a pirate bandana, much to the chagrin of everyone around me. It helped me build an identity that I didn’t have the words for at the time. If you take away the hair, there could be anything under there: it could be long, it could be short. That was really important to me. And I think there’s also something about the billowy shirts: it’s romantic but it’s also quite disguising.

Parry: That’s what New Romantic fashion was saying at the time: that it was OK for men to dress in fabulous things, wear make-up and be flamboyant. All those things are not contrary to masculinity.

Linnea: Pirates became about masculine feminities and feminine masculinities. No matter what kind of pirate you're into it was going to be some kind of weird mash-up, at least within our social context.

Parry: But then we do have examples from history of visual descriptions of real pirates. I suppose the most famous one is Blackbeard lighting his hair and beard on fire and putting fireworks on his head.

Jas: To create his own dramatic entrance! It’s high camp.

Parry: Even in their own time pirates were inventing themselves. No one had ever seen anything like it, and that raises another key point: pirates have always been pop culture figures. They have always been romanticized, and our understanding of the period comes from historical sources that are best highly sensationalized and almost certainly heavily fictionalized.

Why did tattoos become the way to express all these ideas?

Parry: Tattooing is obviously closely associated with maritime life…

Linnea: …but also with queerness.

Jas: Yes. One of the early things we discussed was how tattoos functioned as a kind of code: a sailor’s tattoos would say something that only certain people would pick up on. That idea became embedded within the piece: this work has evolved its own code too.

Are there any secrets you’d like to reveal?

Jas: Some are incredibly camp, like ‘Mother Walrus’ – Queen Anne with a walrus’s head.

Parry: The person in the centre of another tattoo, on the chest, is taken from an historic engraving of a person with dwarfism, assigned female at birth but bearded, wearing a beautiful Elizabethan dress.

Also, the initials of everyone who worked on it are stitched on, plus the initials of some of our historical crushes.

Linnea: Tattoos are so meaningful, and I think a lot of queer people use them either consciously or self-consciously as self-creation. It’s a way of physically marking yourself as different.

Have you though about how people will react to it in the gallery?

Parry: Much of the work I do with silicone bodies plays with edge - blurring the edges of body and costume - where body ends and object begins, or where I end and you begin. They can be challenging to look at, but I hope there’s also an invitation to look closer. A lot of love and tenderness has gone into this piece.

The prosthetic bodies themselves have been mass-produced, and imported from another country: these bodies were literally ‘commodified’. We now have an opportunity to turn them back into something unique and loved through these acts of craft, collaboration and care.

How did the Queer History Club come about?

Phil: It’s one of the few active and vocal queer research spaces linked to a national museum. There are currently more than 80 people in the group, and we hold monthly meetings at the National Maritime Museum.

Linnea: I am an artist and am also really interested in history, but before joining the group I never really knew how to bridge that gap between creativity and academic study. This showed me that I could be interested in history and try to do something weird with it.

Billie: I sometimes had a lack of self-confidence and worried I was too academic: that I’m 'not being queer enough' and trying to be too visual about it. Seeing this approach encouraged me so much.

Phil: There are as many different approaches as there are people within the group. Exploring how we approach things, sharing our knowledge and ideas – that’s what makes it such a brilliant community.

What do you hope this artwork tells us about LGBTQ+ experiences today?

Parry: One of the reasons why I find the pirates Bonny and Read so compelling is that they’re a glimpse in the archive of two people who had transmasculine experiences and were possibly pregnant. We don’t know for sure, but we have a trial record where they say they were. We don’t have many examples from history of people living gender queer lives and experiencing pregnancy – but we know that it will have existed in different ways.

When queer and trans rights are really under attack today, often the flavour of those attacks suggest that this is ‘some new weird fad’. To be able to point to moments in history that challenge those assumptions feels really important.