Astrophotography can often be seen as a solitary pursuit, calling to mind a lone photographer silently snapping away under the stars.

But that’s not always the case. On the contrary, astrophotography can be a very social activity.

Not only do astrophotographers meet up in person to capture images together, but increasingly they are joining forces virtually to collaborate on photographs.

Astrophotographers Sophie Paulin from Germany and Tom Williams from the UK originally met in an online astrophotography forum.

What started out as an exchange of technical advice soon became a friendship. Two years later, after joking that they should climb a mountain to take a photo of Jupiter together, they ended up doing just that.

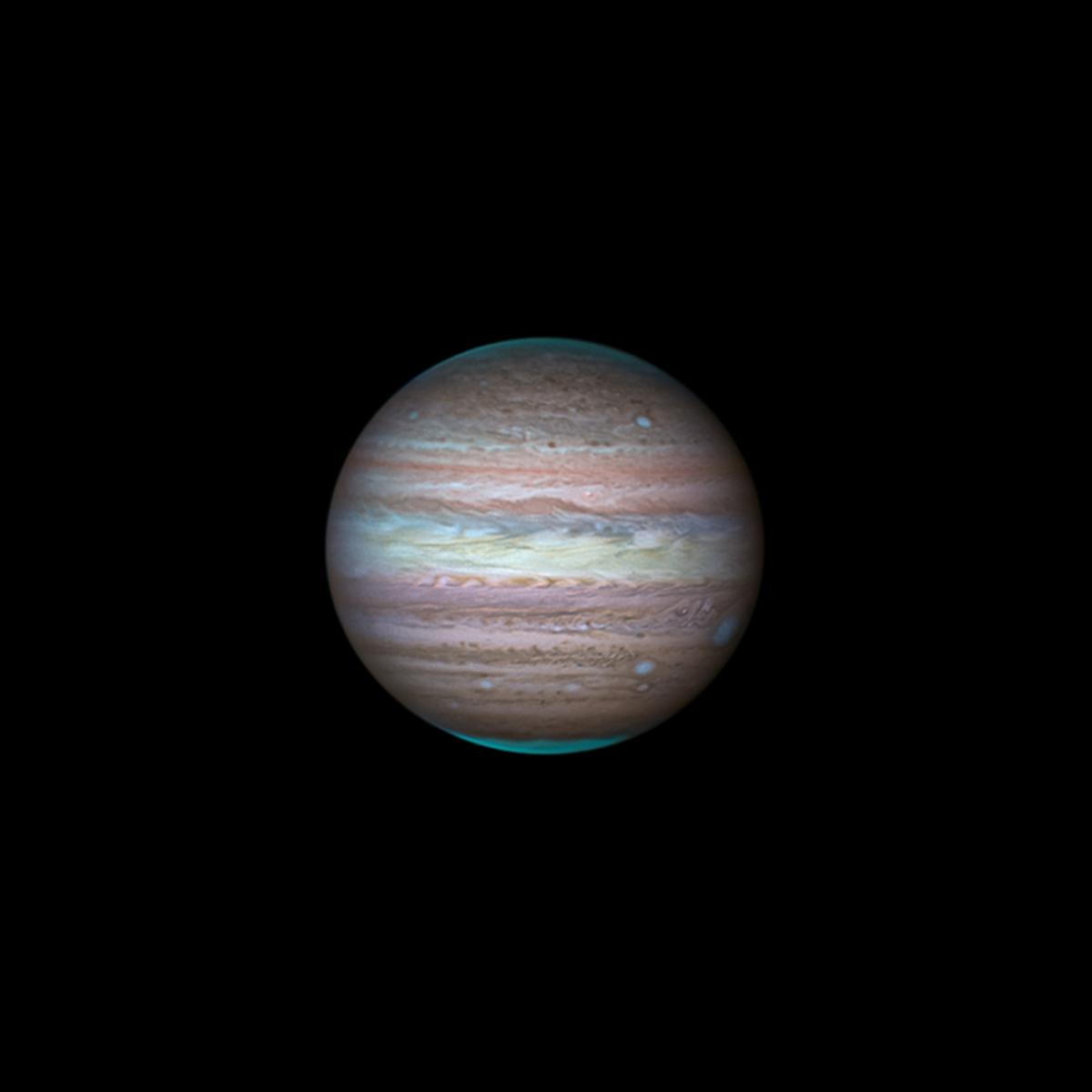

The resulting image, Methane Lights of Jupiter, was Runner-Up in the Planets, Comets and Asteroids category of Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2024.

Discover the story behind Sophie and Tom’s friendship, and why collaboration is pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in astrophotography.

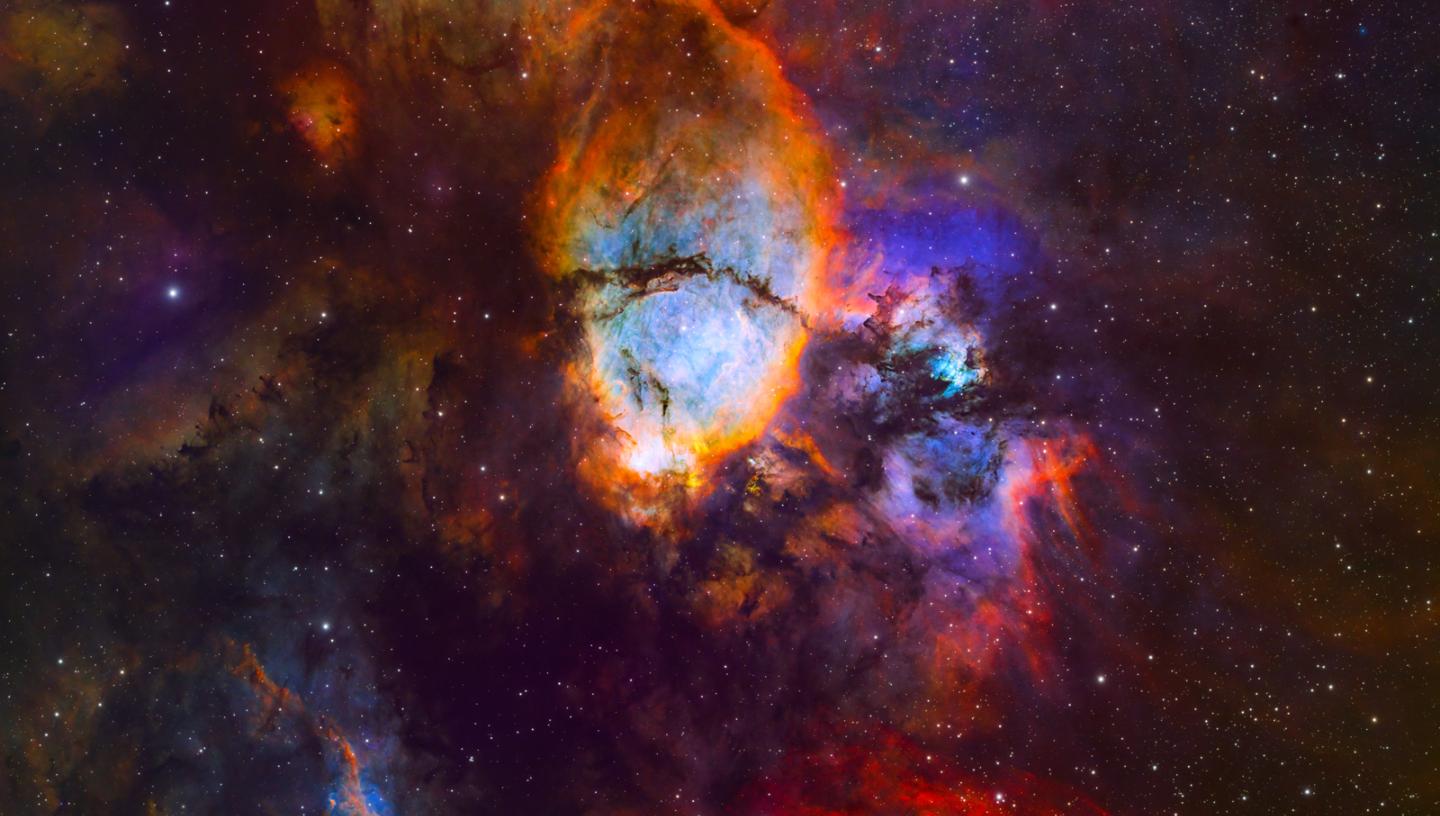

Methane Lights of Jupiter by Sophie Paulin and Tom Williams

“This image shows a unique false-colour view of Jupiter in the CH4 methane-band, with the Great Red Spot setting on the western limb. Intricate upper cloud formations and storms are revealed through the use of visible and methane band filters,” explain Tom and Sophie.

“As most of Jupiter’s atmosphere absorbs light at 889 nanometres, only the bright polar hoods [cap-like features encircling the polar regions] and storm cells remain in the methane channel, resulting in this striking view of the planet. During processing, R-SynG-CH4 was mapped to RGB, with the synthetic green channel being a combination of Red and CH4.”

Teaming up and sharing skills

Astrophotography is a broad umbrella, and different astronomical targets require specific skills and knowledge to capture.

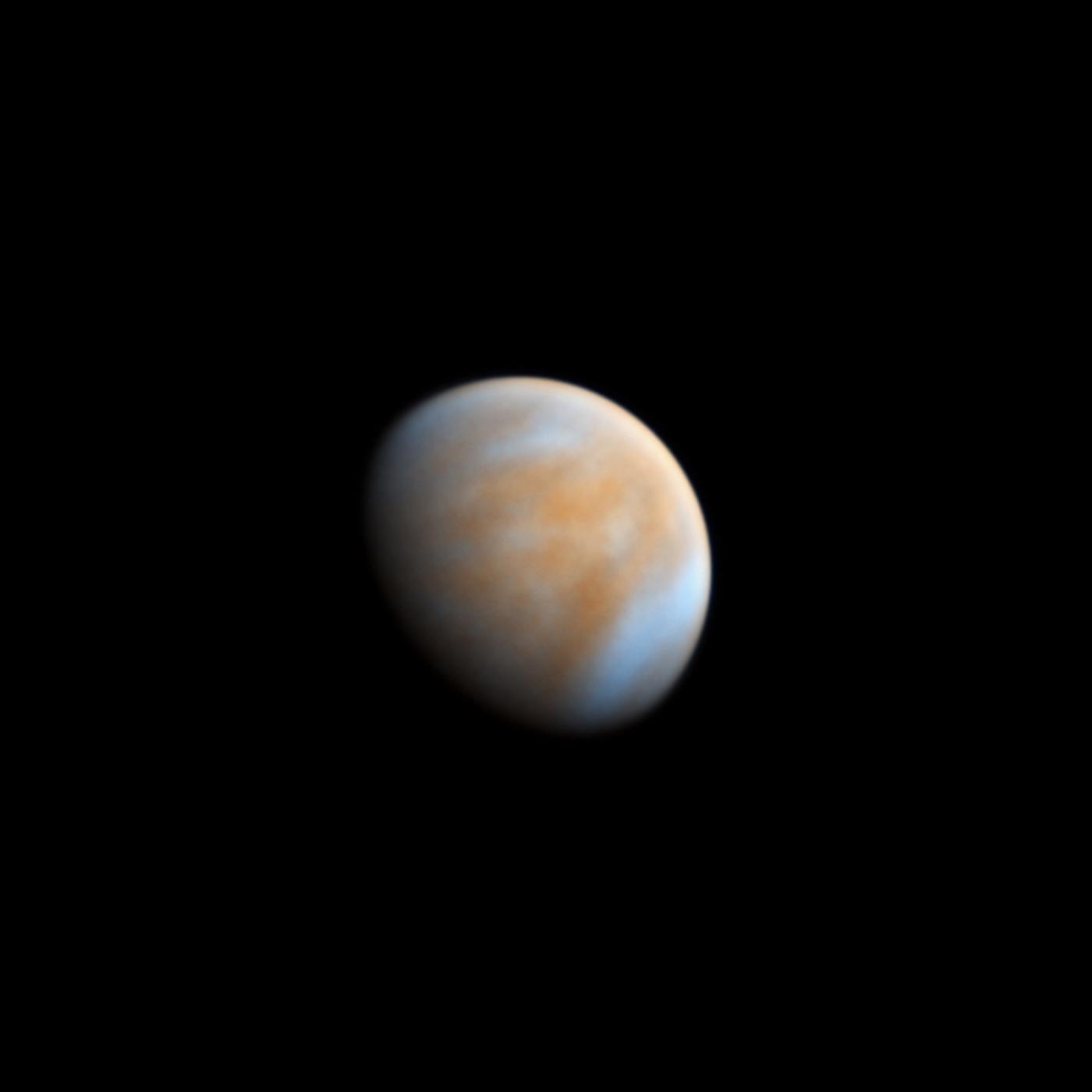

Tom is an expert in planetary imaging. His photo On Approach, which depicts phases of Venus, won the Planets, Comets and Asteroids category in 2024.

This is the second year he’s clinched this title; another of his photos of Venus, Suspended in a Sunbeam, won the category last year.

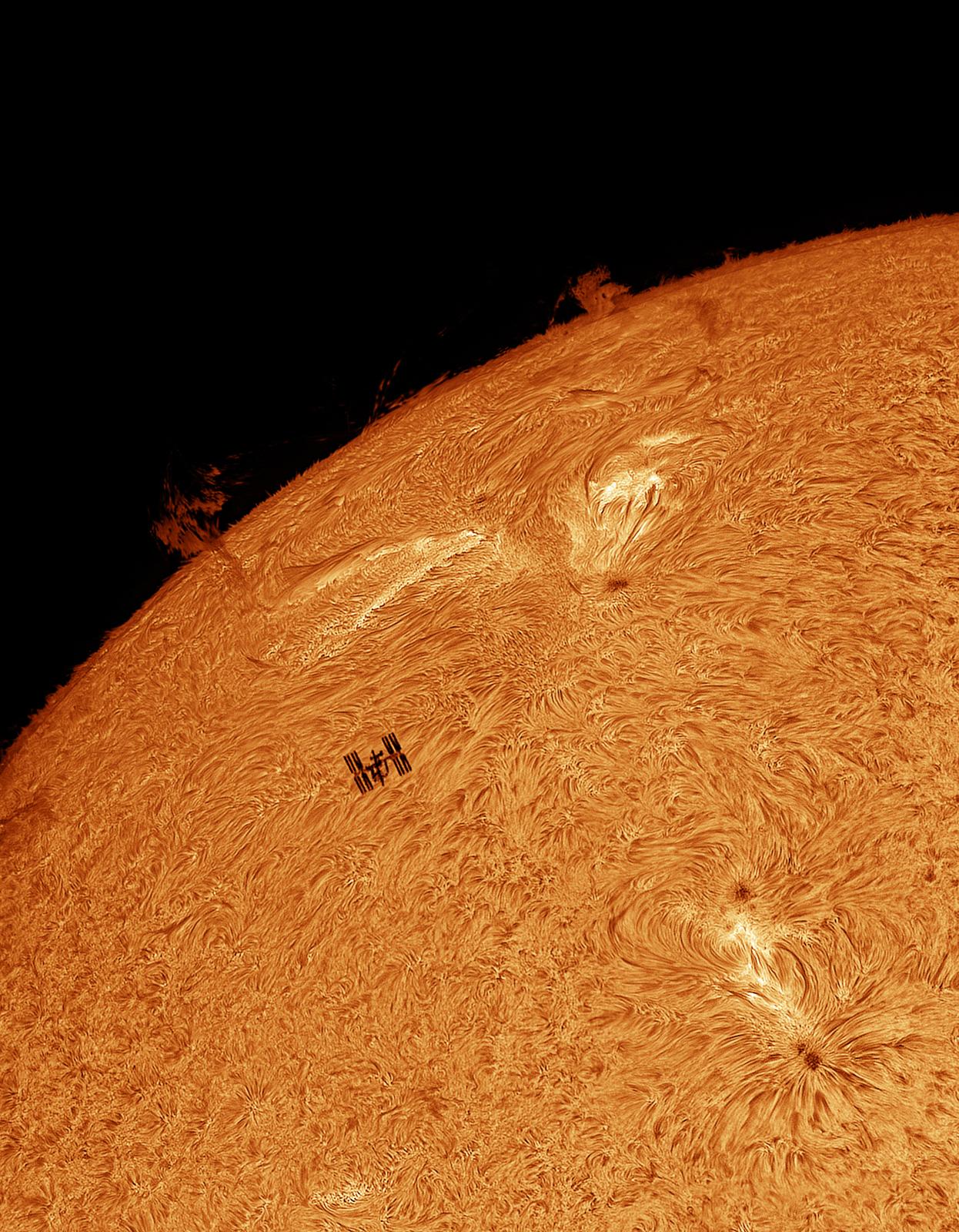

Tom was also winner of the People and Space category in 2024 with High-tech Silhouette, which captures the International Space Station transiting across the surface of the Sun.

Sophie, meanwhile, is talented in deep-sky imagery, having been Highly Commended in the 2024 Galaxies category with A Deep View on the Pinwheel Galaxy with Jens Unger as well as with photo M63, the Tidal Streams Around the Sunflower Galaxy in collaboration with Jens Unger and Jakob Sahner.

“I've never really known someone be so on top of their game in every specialism,” Tom explains. “Deep space imaging, wide field imaging, planetary imaging... they need so much time to master, so if you're alone it's not really possible - or at least it's very, very difficult. I think that's where collaboration is really important.”

He continues: “You can collaborate with whoever is a specialist in certain categories, and I think that's where you can really elevate your game and get the shots you've always been wanting to get.”

Tom and Sophie aren’t the only partnership to find success in Astronomy Photographer of the Year.

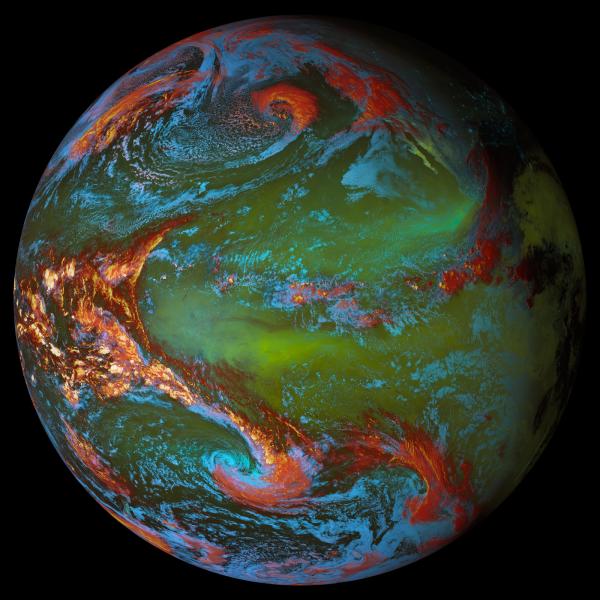

2023’s overall winners, a team comprised of Marcel Dreschler from Germany and Yann Sainty and Xavier Strottner from France, also met online. They used their various specialisms, locations, time and equipment to discover a never-before-seen Oxygen arc next to one of the most photographed targets in the night sky, the Andromeda Galaxy.

Forging friendships

Besides the potential for incredible images, the social aspect of teaming up can make astronomy photography especially enjoyable.

“I started doing astrophotography all by myself, but as I progressed I met more and more like-minded people who eventually became my friends,” Sophie says.

After two years solo, “I started finding more interest and joy in doing astronomy with others – not only because of the fun in the nights you have together, but also because you can share knowledge and problem-solving skills.”

Tom agrees: “You know that you can do it by yourself, but there’s the fun and the sort of adventure side of things.”

Sophie says, “We met two years ago on Discord, an online community platform. We had an astrophotography server and I was taking images of the planets for the first time with my 8-inch telescope. I had some questions about atmospheric dispersion and whatnot. Tom helped me to answer those questions.

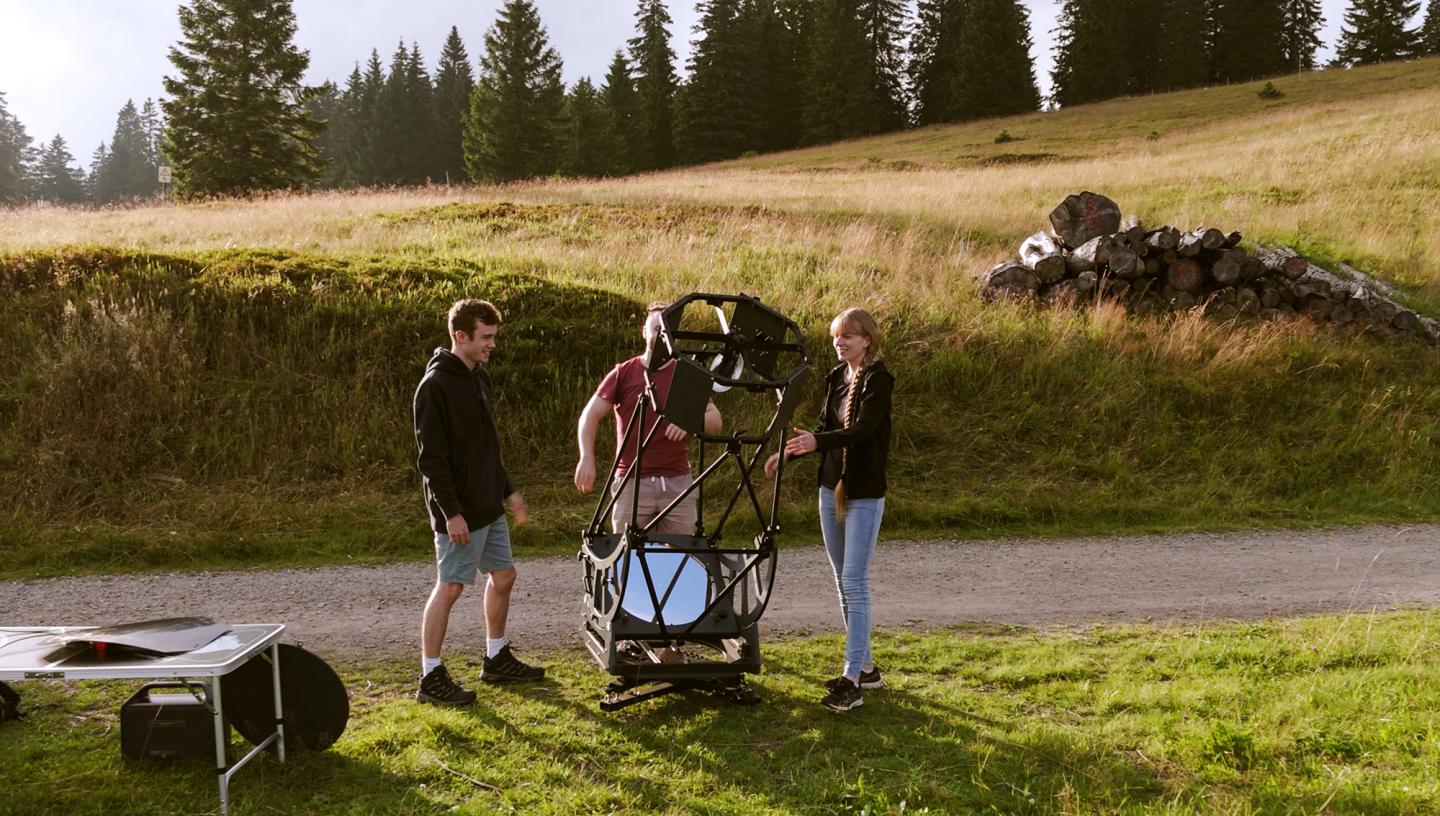

“I got interested in shooting planets and I really wanted to get a bigger telescope, because with a bigger scope you get better images essentially. So I got the scope here and Tom and I talked about how we could put it on a mountaintop and shoot the best image possible with it.

“And, well, suddenly it was no longer a joke! Tom flew to Germany and we actually took an image on Edelweißspitze in Salzburg, Austria.”

Taking the photo

“Our image was actually captured on the first night that we had the telescope set up,” says Sophie. “We built it during the day and spent the whole day aligning the mirrors.

“It probably would have been impossible to get such a perfect shot on the first night without working together to get the scope running, with all its quirks and difficulties.”

Tom adds, “We were really time pressured because we knew the conditions were going to be good, and obviously being in northern Europe, it was a rare occurrence. So we knew how much it mattered, and had to pool all our knowledge to get this up and running in time. And luckily the atmosphere cooperated as well.”

Sophie explains the different roles they took on the night: “When we took this image, Tom was controlling the software on the PC and I was controlling the mount – the platform the telescope was riding on.

“Together we took the data and Tom then processed it to show off these colours.”

What does the image show?

Sophie explains, “This image shows Jupiter and its methane gases in false colour.”

False colour is where, during the processing of an image, colours which are not present in the object are used to enhance, contrast or distinguish details.

Sophie continues, “Usually methane isn't blue, but in this image we mapped the methane band to blue, so you can clearly see where methane is present in Jupiter's atmosphere."

“It's sort of representative of just how dynamic the atmosphere is, and it's in a slightly different colour palette to the usual visual."

Tom explains why he made this choice: “The main reason we processed the image in this way is so that we could see Jupiter in a different light, because it's so common that people image it in RGB [red, green and blue] or the visible spectrum as it appears to the eye.”

Competition judge Kerry-Ann Lecky Hepburn said, “They have done a great job incorporating both CH4 [methane] and RGB colour data. The outcome is an excellently processed image, with very pleasing and natural colours – I can’t imagine that was an easy task.”

A supportive online community

Sophie finds that the astrophotographers she encounters online are more than willing to offer help to those looking to progress on their astrophotography journey.

"The astronomy community is one of the nicest communities I've met. Everyone is so eager to help each other and share solutions for all the problems they encounter. It’s so rare to have this nowadays in other communities.

"Back when I started out, I had many questions and many people in our online community helped me, just like Tom did back then when I started with planetary photography.”

Tom hopes that by sharing their story, more people will be inspired to pick up a camera and connect with new people.

“I think the main message is, you know, go out there and speak to people! Make these things possible."

“I'm glad that everything went the way it did; it was awesome. It started out online, but then I found myself hundreds of kilometres away doing what I love."

You can see more of Sophie's astrophotography on Instagram and Astrobin and more of Tom's astrophotography on Instagram and Astrobin.

Never miss a shooting star

Sign up to our monthly space newsletter for exclusive astronomy highlights, night sky guides and out-of-this-world events from the Royal Observatory.