N.A.M. Rodger’s ‘Naval History of Britain’ encompasses more than 1,000 years of history and a lifetime of research.

It is an undertaking which the National Maritime Museum has been proud to support for more than 30 years. The final volume of Professor Rodger’s work, The Price of Victory, will be published on 24 October.

But how does an author even begin to confront such a broad sweep of history? The unexpected answer lies in an obscure corner of the Civil Service...

Specialization is both the blessing and the curse of modern scholarly writing, especially for the historian.

It is a blessing which makes it possible for overworked lecturers and teachers to choose a subject defined narrowly enough to allow them to master and dominate it. It is a curse which, at least in naval history, leads to ever-more numerous studies of single battles or campaigns, and ever-fewer writers ready to risk their reputations on the broad sweep of history.

Anyone who visits a good bookshop will be able to gather numerous history books, but even the best of them tend to be written from sources in a single language, from the perspective of a single country and often a single service. All too often, these studies largely repeat the interpretations of an older generation.

The literature in English on the Second World War at sea, for example, is still heavily dominated by the memoirs and biographies of the admirals and politicians of 80 years ago. Only one massive collective work produced by the Militärgeschichtliche Forschungsamt (German Armed Forces Historical Institute), Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg (Germany and the Second World War), has tackled the whole sweep of the war from the original archives and sources of all the participants, but not all of it has yet been translated from German into English. The result is that this great achievement has had much less influence than it deserves, while far too many books published in Britain and the United States still reflect old-fashioned and untenable ideas.

Similar criticisms can be and are made of many other periods and subjects of history. Though the contributions of many countries to modern history have been evaluated by official histories, most of these works are drawn from more or less partial sources, and none has approached the scope and critical rigour of Das Deutsche Reich. Still less have individual scholars revived the magnificent self-confidence of the Victorian era and tackled such extensive ranges of history single-handed.

I myself was never in any sense a magnificent Victorian. My career was shaped by several unplanned strokes of fortune, including getting into Oxford without the statutory entrance qualifications when my papers were lost in the college messenger system. After my undergraduate degree I did a doctorate and dreamt of a junior lectureship in one of the new universities.

Instead I was taken in by an institution I had never heard of: the Public Record Office (the predecessor of the National Archives). The time is not ripe to release my memoirs of serving in this remarkable (and then eccentric) institution, but I nevertheless count myself extremely fortunate to have spent 17 formative years in what was undoubtedly the last refuge of the gentleman scholar.

The PRO in those days believed that an Assistant Keeper of the Public Records should be capable of handling all sorts of government records from the Norman Conquest onwards. The assumption was that he or she would already possess, or mysteriously acquire without formal instruction, the knowledge to read any language and script which might be encountered in the public records.

This was the polar opposite of the modern academic culture of narrow specialization; the Office regarded specialist knowledge as vulgar and unseemly, and severely discouraged historical publication. Had I been taken on as a junior university lecturer after writing a doctoral thesis on British naval policy in the 1870s I would have been typecast as a specialist in that period, and no doubt set to teach courses on Disraeli and Gladstone from that day to this. Instead I was identified as a new Assistant Keeper appallingly ignorant of real (meaning medieval) history, and given an Exchequer Roll – the ‘King’s Remembrancer’s Memoranda Roll for the 56th regnal year of King Henry III (Michaelmas 1271-72)’ – with a brief instruction: “We think there are about 50,000 proper names in this roll. Identify them and make an index.”

I was then left to myself to learn what information the roll recorded, to master the heavily abbreviated Exchequer Latin, to identify the persons and places named, and to understand how public administration worked in 13th-century England. It took about nine months, but it was a deeply satisfying challenge, better than any detective story - the first of many introductions to new kinds of document, new languages and hands, new realms of history. After 17 years of this sort of work I had acquired (by happy accident rather any personal merit) an historical education of a breadth and chronological range which few of my contemporaries could match.

In 1991 I decided to put this historical training to use by leaving the Record Office to write a ‘Naval History of Britain’, meaning a broad study of naval warfare as a key factor in shaping the history of the British Isles, starting after the end of the Roman era, and running up into the 20th century.

It would have to be a work of synthesis, based on the published researches of many scholars, since many lifetimes would be needed to cover such a sweep of history from original archival research, but my ambition was to trace the naval dimension of the history of the British Isles – and those other regions of the world which were affected for good or ill by British overseas expansion – with the coherent and consistent point of view that only a single author can deploy.

I do not doubt that other historians could have done it better, and I still hope to encourage them to try, but I think I can at least claim that an unlikely chain of unplanned good fortune endowed me with an historical upbringing which was uniquely suitable for the task.

Nobody now could set out on a voyage of discovery similar to mine. We have many more (and, I believe, better) naval historians today than there were 50 years ago, and the modern National Archives has inherited the historical records I studied, but the old Civil Service class of Assistant Keepers of the Public Records with their haphazard and unprofessional formation are no more. No-one now could be trained (or untrained) as we were, but perhaps the three volumes of my ‘Naval History of Britain’ may survive to demonstrate that the old régime of the Public Record Office was not wholly without merit.

Much greater credit is owed to the unstinting generosity of the National Maritime Museum, which made me its Anderson Senior Research Fellow from 1992 to 1998, and has continued to support the publication of the three successive volumes for 30 years, notwithstanding the delays imposed by a serious illness. The Museum’s support has been fundamental throughout the life of this project. Few other public or learned institutions have displayed such heroic generosity over so long a period, and few other historians have been so fortunate as to enjoy such patronage.

About the author

N. A. M. Rodger is a Fellow of the British Academy, Emeritus Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford and former Professor of Naval History at the University of Exeter. In 2024 he was awarded the Caird Medal of the National Maritime Museum, and he has been awarded the Julian Corbett Prize in Naval History, the Duke of Westminster’s Medal for Military Literature, the British Academy Book prize and the Hattendorf Prize.

The Price of Victory, the final installment of his definitive, authoritative trilogy on Britain's naval history, is available to pre-order now.

Find more stories you might like

Find more stories from Royal Museums Greenwich curators, collections and publications.

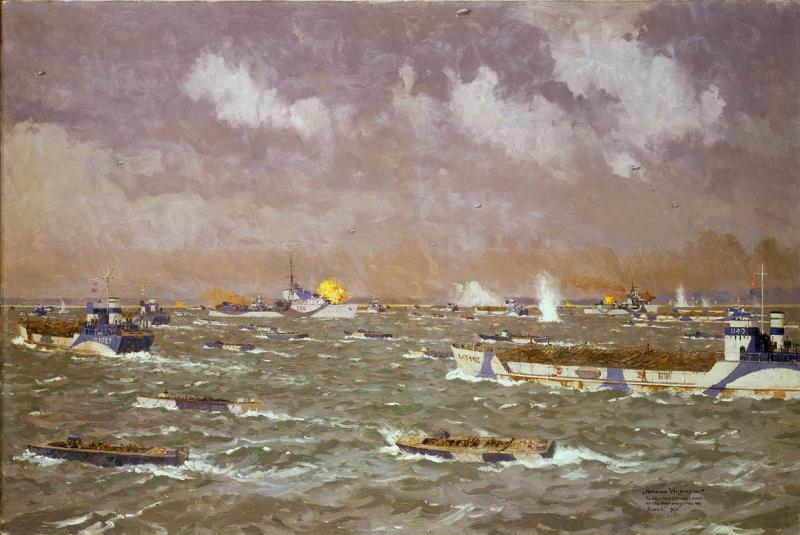

Main image: The Battle of Navarino, 20 October 1827 by George Philip Reinagle (BHC0623)